In Haiti Betrayed, B.C. documentary filmmaker confronts impacts of Canada's foreign policy

Writer-director-producer Elaine Briere examines the role Canada played in the 2004 coup in the world’s first free Black republic, and much more

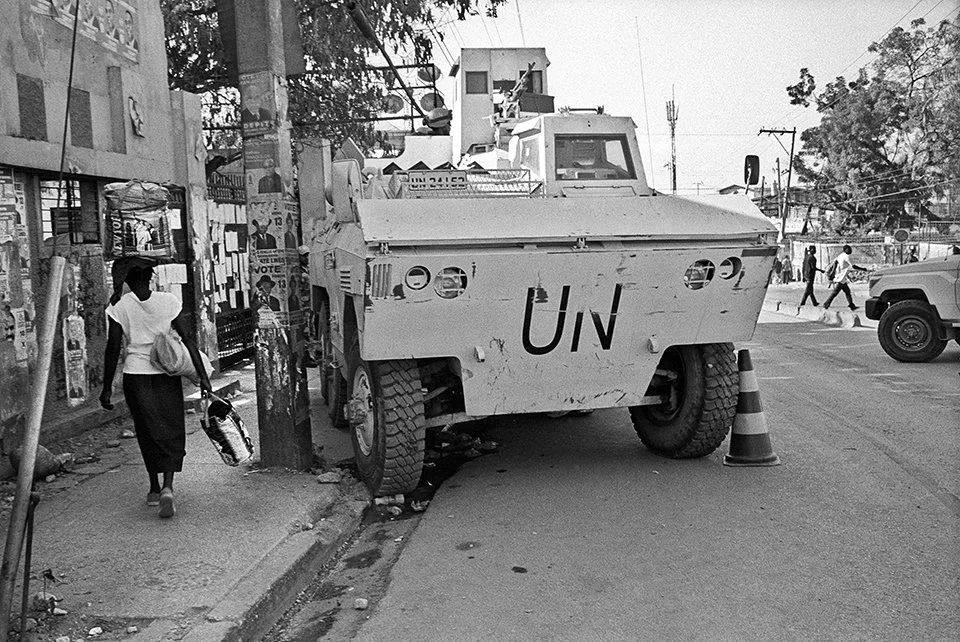

Haiti Betrayed.

Haiti Betrayed screens at VIFF Centre’s Vancity Theatre on January 28 at 12:30 pm (tickets available at the door); talkback follows with director Elaine Briere, aid worker David Putt, and former Haitian National Police officer Garry Auguste

IN 2004, CANADA helped overthrow Haiti’s democratically elected government. The covert forced removal of President Jean Bertrand Aristide to Africa plunged the nation into a state of chaos, corruption, and violence. The situation has only gotten worse over the years, as headlines have blared. Less widely known is the role that Canada has played in the country since the coup and, according to Haiti Betrayed, in helping prop up successive Haitian governments controlled by some 20 dominant families.

Seven years in the making, the documentary by B.C.-based filmmaker Elaine Briere offers a sobering counterpoint to the widespread narrative that Canada has been providing much-needed assistance to the nation out of purely humanitarian motives. It exposes Canada’s role in the coup, the immediate bloody aftermath, the manipulated elections that followed, and more.

Endorsed by Noam Chomsky, Haiti Betrayed features interviews with Garry Auguste, a former Haitian National Police officer; Kingston University scholar Peter Hallward; Bobby Duval, founder of the youth-focused Athlétique d’Haïti; Sue Montgomery, a former Montreal Gazette reporter; and Brian Concannon, executive director of the Institute for Justice & Democracy in Haiti, among many others.

“The Canadian people are kept deliberately ignorant of the Haitian reality,” Haitian activist Patrick Elie, former Minister of State for Public Security, says in the film. “They see the misery and they respond to the suffering, but they do not address the role of their own government in this suffering.”

Elie later notes: “When slaves—cattle—liberate themselves, you cannot have a worse nightmare for the powerful countries. Haiti must be made to fail and to simmer in misery.”

Some history, that’s shared in the film via archival material: In 1804, General Jean Jacques Dessalines proclaimed the independent Black republic of Haiti after rebel slaves defeated French army troops. Haiti was the first nation ever to successfully gain independence through a slave revolt. Seen as a major threat to the colonial order and institutionalized slavery, Haiti was not recognized as a country by the U.S., much of Europe, or the Vatican for more than 60 years. In 1825, Haiti was forced to pay millions of francs to France on threat of reoccupation. No other country in the world has been forced to pay its colonizer for loss of slaves and territory. Those payments, totalling US$28 billion, went on until 1952, impoverishing the country.

Fast-forward to the mid-1900s, and the decades were marked by dictatorship under Francois “Papa Doc” Duvalier and his son, Jean-Claude “Baby Doc” Duvalier. Aristide, a populist priest of the social-democratic political group Lavalas, was the landslide winner in a presidential election in 1991, Haiti's first free and peaceful election. He was overthrown by the military in 1991 and returned in 1994, then taken from his home in 2004, at night, by U.S. Navy Seals while Canadian military secured the airport from where he was flown into exile. The film shows RCMP members on the ground later that year training officers for the Haitian National Police, a force, the film relays, that routinely sought out supporters of the democratic Lavalas government. Approximately 4,000 pro-democracy civilians were killed, while Haiti’s jails were packed with political prisoners.

“When prime minister [Paul] Martin in the fall of 2004 said that there were no political prisoners in Haiti, that undermined the efforts by human-rights advocates and pro-democracy activists in Haiti and abroad to try to bring an end to the repression,” Concannon, a human-rights lawyer, says in the film.

Elaine Briere.

Briere—whose Bitter Paradise: The Sell-out of East Timor won Best Political Documentary at the l997 Hot Docs Film Festival—was unaware of the situation in Haiti and of Canada’s related foreign policy until she visited the country in 2009 with her husband. He was the director of an NGO implementing clean water and sanitation projects in Port-Au-Prince. While Briere was taking photos in a major square in the city centre, a man, assuming she was a journalist, approached her. (She is also a photojournalist who has exhibited around the globe.) He said to her: “They are killing us! We are poor people. Life is very hard. Tell them what they are doing to us. Tell them to stop! Tell them to stop!” He started crying.

That encounter impelled Briere into the years-long documentary project.

“I began photographing around town and meeting people, especially teachers in schools where my husband did water projects, and I would ask them about Lavalas and Aristide,” Briere tells Stir in a phone interview. “They told me the exact opposite of what the media was telling us up here. It was a very popular government that was building schools and improving education, public health, and fiscal management. It was fragile, constantly undermined by the U.S. and later by France and Canada and by a negative foreign-press narrative. The abuse of Haiti by Western countries from the very beginning, in 1804, when they won their freedom from France, has just been one thing after another.

“We all owe a debt to Haiti because Haiti asserted the right to be free of human bondage and that all people had equal rights regardless of their skin colour,” Briere adds. “It was really the beginning of the modern human-rights movement.”

Packed with details as well as original and archival footage and photography (much of it taken by Briere), Haiti Betrayed includes commentary from exasperated civilians; Amnesty International; and Haitian-Canadian activist Jafrikayiti (Jean Saint-Vil), who splits his time between the two countries.

“It was really tragic for us when we started to understand that the Canadian government was actively undermining the Haitian government,” Saint-Vil says, later noting: “The fundamental thing you observe when you go to Haiti is that there is social injustice at a level that is simply unacceptable, and that injustice is precisely what the nation was created to fight.”

Haiti Betrayed.

The situation in Haiti has only deteriorated since 2004, in part due to the 2010 earthquake—the worst in Haiti in over 200 years. The film describes how also in 2010, Lavalas was blocked from running candidates in elections funded by Canada and the U.S.

Briere acknowledges that there are many complex factors affecting the nation beyond what's contained in the film. The documentary brings things back to the voices of so many living there. An unnamed man is captured shouting at a Canadian Embassy building in Haiti: “We don’t have anything against Canada! Why are you against us? The Haitians aren’t against you! Why do you hate us?”