Arushi Jain brings ever-evolving electronic mindscapes to Indian Summer Festival

Having trained in North Indian classical singing, the artist speaks her own musical language filled with computer-based sound

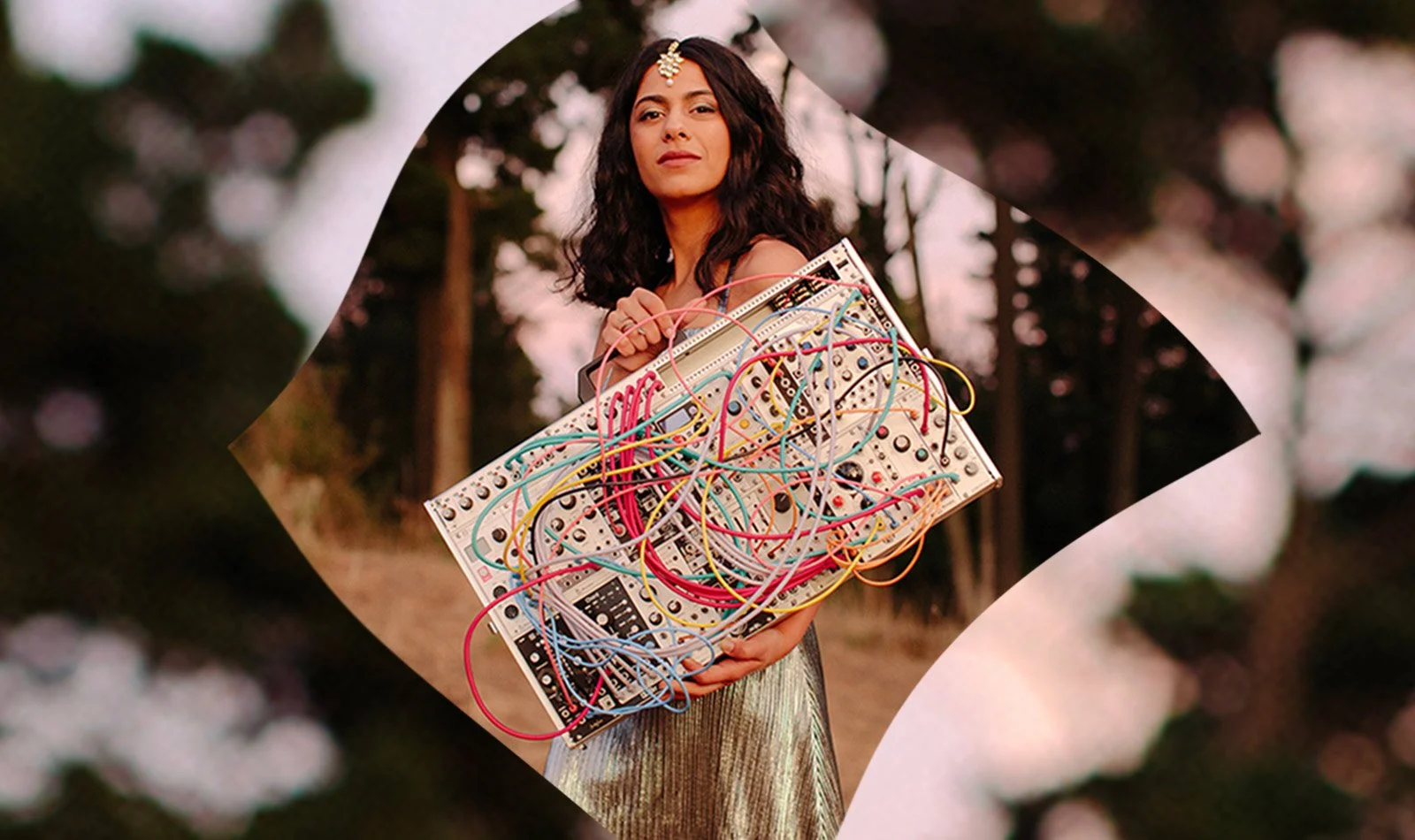

Arushi Jain.

The Indian Summer Festival presents Arushi Jain at Performance Works on July 11 at 7:30 pm with Sheherazaad and Piu in a copresentation with PuSh International Performing Arts Festival

IT’S WINDY IN San Francisco. Just beyond a wooden deck silvery foliage is shivering in the breeze, and in the foggy distance hints of the fabled Bay glint dimly. It’s the figure in the foreground that’s holding our attention, however. A young woman in a white robe, giant headphones covering her ears and a glittering diadem on her brow, is manipulating dials behind a bright tangle of multicoloured cables, and the sounds thus generated are at once familiar and like nothing we’ve ever heard before.

Arushi Jain, here operating under her Modular Princess stage moniker, twists a knob and a rich drone emanates from unseen speakers. It’s an obvious nod to the four-stringed tanpura that sets the pulse for most North Indian classical ensembles, but it’s accompanied by an electronic pinging that speaks to a different continent and a different mindset; perhaps Berlin in the 1970s. When Jain begins to sing, in her subtly processed soprano, we’re pulled back to her native Delhi, but not entirely. Waves of white noise and electromagnetic space pulses place the listeners in a freshly minted non-space that exists only in Jain’s mind—and, now, in ours.

For many listeners, Jain’s 2020 online concert, part of the Boiler Room: Wild City series of pandemic performances, was their introduction to this singular talent. Others came on board with the recent release of her album Delight, a more polished and more collaborative effort that fully lives up to its title. Still more will get a chance to experience Jain’s music when she headlines an Indian Summer Festival concert at Performance Works on Thursday (July 11). The artist’s own introduction to her own ever-evolving electronic mindscapes, however, came during a time of personal sorrow and confusion, some time after the former Ravi Shankar Institute student had arrived in California to pursue a degree in computer science at Stanford University.

“I was going through a huge identity crisis a few years ago where I was like, ‘Where do I exist?’” she told Composer magazine’s Chal Ravens in 2021, adding that for three years following her arrival in the United States she was artistically adrift while simultaneously being fiercely focused on her education.

Now, in a Zoom conversation from her present home in New York City, Jain doesn’t disagree with that assessment. “I just never studied music in the way that any of the people around me had,” she explains. “When I moved to California, nobody around me spoke the same language, from a musical perspective, because I don’t think in harmonies. There are just so many things I didn’t learn, because I have a different musical background, and I just felt like I would never be able to do anything with it.….That was what was happening for me in that moment, because of all the change and the newness of moving somewhere so far away, and because I didn’t play an instrument other than my voice.”

It’s not that Jain wants to downplay the experience of being a new immigrant, which certainly shaped her artistic vision, but she doesn’t want to dwell on it either. What she would like to stress is that she eventually found a way to apply her obvious intelligence—“I think I’m quite a logical person,” she notes—to the situation.

“Having a void, having a reason to miss something, is important, because it helps you realize why it matters to you in the first place,” she says thoughtfully. And, having decided that music itself mattered more than the specifics of her earlier training in North Indian classical singing, she ventured into the infinitely expandable world of modular synthesis and computer-baed sound. Working with electronics, she says, is like inventing a new instrument with every patch or program—and that, coupled with her voice, has given her access to a singular world of sound.

“Singing on its own, without anything? It’s fun, but it’s not like my life,” she says. “The reason I love the modular synthesizer so much is that it gave me an instrument with which I could write and compose not just melodies, but also literal instruments and sounds. And that, paired wth singing, creates a whole new thing for me. It’s like I’ve broken some kind of barrier.

“Computers are like an extension of my brain,” she adds. “Studying computers taught me a lot about information organization, and information organization, as a worldview, is a way to look at modular that makes it a lot easier for me to understand what’s going on.”

The most marvellous aspect of Jain’s work, however, is that it avoids the paint-by-numbers simplicity of much sampler- and sequencer-based music. Instead, it offers a richly human emotional experience, something that’s especially audible on Delight. Centred on her voice and synthesizers—and on the ageless tones of Raga Bageshri, a melody designed to invoke that bittersweet feeling of waiting for a lover’s return—also introduces a new cast of collaborators on acoustic instruments, including cello, classical guitar, marimba, flute, and saxophone.

Unalloyed loveliness is the result but, as Jain notes, achieving such sustained beauty is far from a matter of luck.

“The idea of the album is this concept of working for delight—the idea that things like that don’t fall into your lap,” she says.”You have to create them for yourself in your life and in your work. It doesn’t just happen.

“I can go on about that, but let’s just say that if that’s the thing I wanted to say with this album, then comes the idea of ‘How can I say that in a way that is beautiful?’” she adds. “That’s part of the intent: I want to make a gift that is full of beauty and love.”

![]()