Sax master Donny McCaslin finds unconventional new terrain between jazz and rock

The New York City artist works collaborative magic with the likes of B.C.’s Ryan Dahle and Flaming Lips producer Dave Fridmann

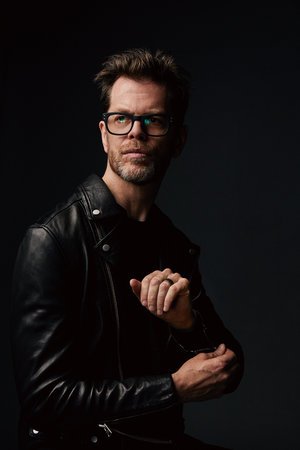

Donny McCaslin.

Donny McCaslin and his band play the BlueShore at CapU on Sunday, September 24

IN THE WEEKS LEADING up to the West Coast tour that will bring his quartet to the BlueShore at CapU this week, Donny McCaslin found time to prepare a gift for his local promoters: a short cellphone video in which he enthusiastically sings Vancouver’s praises.

“It’s just such a beautiful place,” he says, speaking into his cellphone camera with unfeigned enthusiasm. “And I feel like there’s a warm arts community there that I love tapping into.”

Our operatives have not yet determined whether he made similar recordings for Albuquerque, New Mexico, and Monterey, California, but it’s obvious that the saxophonist’s ode to our town wasn’t just an ingratiating stunt. McCaslin really does love B.C., and with good reason. On previous visits to the Lower Mainland, he’s struck up enduring relationships with the students and staff of Capilano University’s jazz program, where he’s taught master classes and guested with the resident choir. This summer, he spent a few weeks on the road with part-time Vancouver Island denizen Elvis Costello, and some of the most powerful moments on his 2018 release Blow came from collaborations with Mayne Island’s Ryan Dahle, best known locally for his work with the radio-friendly rock band Limblifter.

Should the California-born, New York City–based saxophonist spend more time here he’d be well advised to apply for dual citizenship—and in recent years McCaslin has resided in two very different zones: rock and jazz.

Most notably, he was the bandleader on the late David Bowie’s posthumously released Blackstar album, after the British superstar caught him soloing with Maria Schneider’s big band. That relationship has been covered at length elsewhere, including by this writer. The Coles Notes version, though, is that the two influenced each other: McCaslin and his bandmates brought state-of-the-art electric jazz sophistication to Bowie’s eerily prescient meditations on mortality, while Bowie encouraged the jazz players to mix their unparalleled chops with more populist moves. That led to McCaslin’s collaboration with Dahle, which is ongoing, and also to his quartet’s new I Want More, mixed and monkeyed with by multi-instrumentalist and Flaming Lips producer Dave Fridmann.

“The music for I Want More was conceived during lockdown, and I was pondering if I would ever play live again, and if I did, what would it look like. What would I want to do?” McCaslin explains. “I was ruminating on that, just that I wanted to get back to playing instrumental music with these folks that I have a lot of shared history with. So it was conceived and recorded during Covid, and the Dave Fridmann connection happened, actually, through Ryan.

“He was one of the folks who was a guest on my last record, Blow,” he continues. “We cowrote some songs together, and he sang on the record, and subsequently we did some touring together. We also started writing new songs—we have this whole record of material that is yet to come out—and it was during that process that he had mentioned his admiration for Dave Fridmann. He gave me some examples of mixes that he really loved, and then Steve Wall, who produced and mixed Blow, had also mentioned Dave Fridmann at some point. So I thought ‘Okay, here’s this name coming up from two different people who I really respect, so it’s worth investigating.’ I started listening to things that he’d worked on, and just immediately I found his sonic imprint very compelling. So an introduction was made, and we started working on things. I would send him these tracks that we’d recorded, and what he came back with was, to me, astonishing.”

By jazz standards, Fridmann definitely made a few of what McCaslin calls “provocative choices”.

“‘Body Blow’ comes to mind,” he says. “After we get into the melody and the saxophone solo starts, there’s just all of this low-end distortion and, like, awfulness.” He laughs, and continues: “I’m not sure how to describe it to you, but there’s this whole world of sound that happens. Of course, it’s really related to what we played, but he’s also added some more danger in there, which I love. Another example would be ‘Fly My Spaceship’, the way the bass is so upfront in the mix. It’s so, you know, meaty, and it’s not how jazz records are mixed.

“Not that this is a jazz record per se—I mean, that’s another conversation—but that was a choice where I went ‘Wow! The bass is really in front, and it’s really powerful.’ I might not have turned the bass up that much if I was doing it myself, but he did it—and once I got over my initial surprise, I could hear the beauty of it and how compelling it was.”

One area in which I Want More hews to jazz orthodoxy is that the music is more or less collectively composed, although with McCaslin very much in the driver’s seat. He returns to “Fly My Spaceship” as an example: it started during a soundcheck in which bassist Tim Lefebvre was toying with a new ring-modulation pedal and came up with the aforementioned bass part. McCaslin made a quick cellphone recording, took it home, and then turned it into a tune. Drummer Mark Guiliana worked on the beats, keyboardist Jason Lindner added dubbed-out synth effects, Fridmann worked his unconventional magic, and the recording was done.

“Those guys have such rich imaginations that I just leave it to them, or I give brushstrokes,” the bandleader says. “But part of the beauty of the way we play together, I think, is just the implicit trust that we have, based on all this shared experience we have on the bandstand and in the recording studio. I just want to create an environment where everybody feels free to bring their creativity full-bore into what we’re doing.”

That certainly sounds like jazz, even if the music doesn’t always.