Trayvon Martin's death inspires theatre piece Our Fathers, Sons, Lovers and Little Brothers, at PuSh Festival

Playwright-actor Makambe K. Simamba draws on the story of the Black teen’s life in powerful solo show

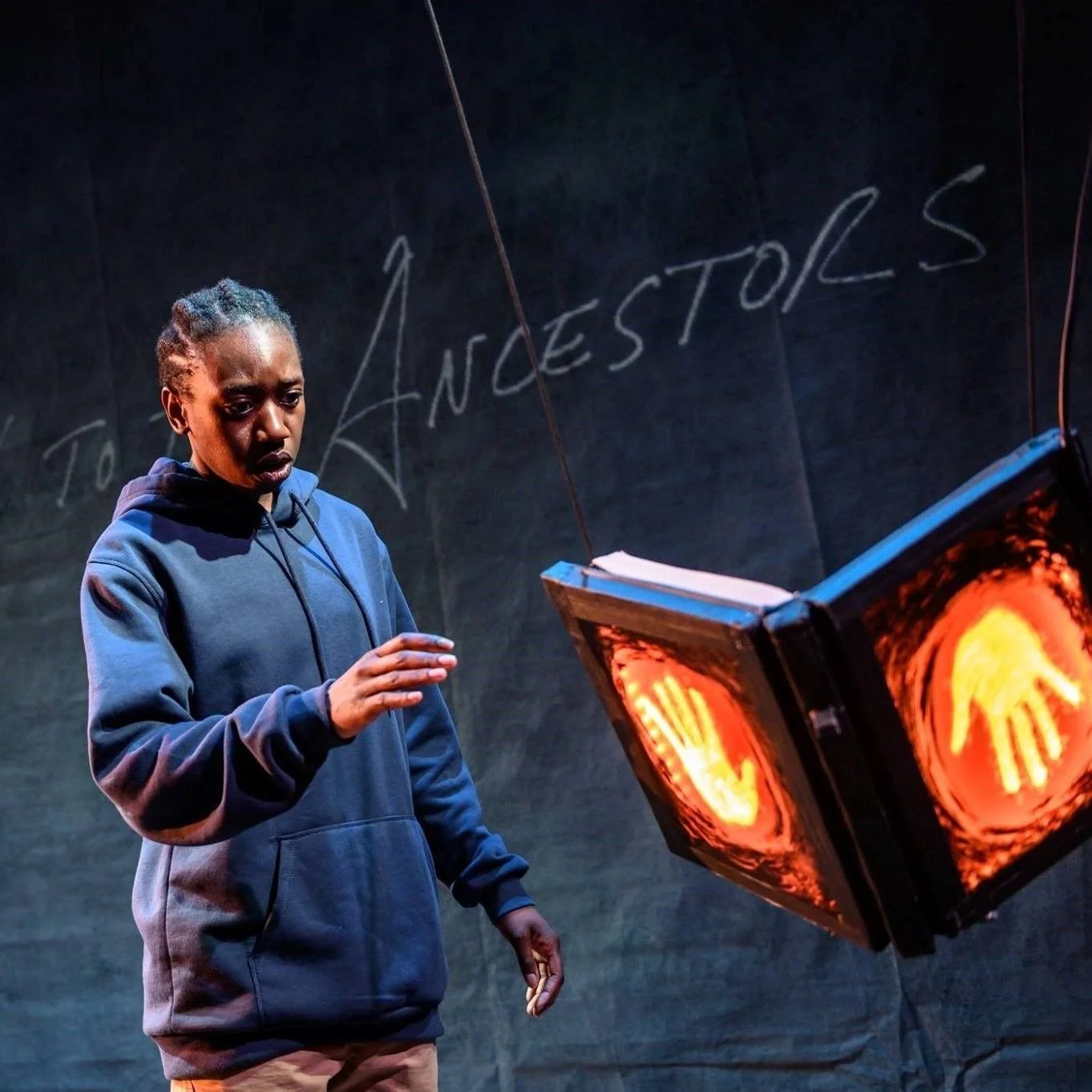

Makambe K. Simamba in Our Fathers, Sons, Lovers and Little Brothers. Photo by Marco Kova

UPDATE: On January 17, PuSh Festival announced the cancellation of the Vancouver performances due to a confirmed case of COVID within the visiting company. “The safety of patrons, staff, crew and artists must continue to be our top priority, though we are greatly disappointed to be making this announcement,” PuSh said in a statement.

PuSh International Performing Arts Festival, Firehall Arts Centre, and Touchstone Theatre present Our Fathers, Sons, Lovers and Little Brothers by Makambe K. Simamba —Tarragon Theatre and Black Theatre Workshop (Canada) on January 20 and 21 at 7:30 pm and January 22 at 3 pm and 7:30 pm at the Firehall Arts Centre. A post-show chat takes place after the January 21 performance.

TRAYVON MARTIN WAS just 17 years old when he was shot and killed in Sanford, Florida by a neighbourhood-watch member named George Zimmerman on February 26, 2012. The unarmed Black teen’s murder—and Zimmerman’s eventual acquittal—sparked nationwide controversy and unrest over racial profiling and oppression.

For theatre artist Makambe K. Simamba, who is Black, the youth’s senseless death and his grieving family’s fruitless search for justice hit especially close to home: at the time, her beloved younger brother was around the same age as Martin was when he died.

“I thought to myself it was such an awful, heart-breaking, and confusing story, that somebody’s child was dead, and the reason why wasn’t making sense,” Simamba tells Stir by phone from Toronto. “The reason I really felt connected to the story is because of my brother, this teenage black boy who I love… I thought to myself, If anything ever happened to him I would be devastated, and if something worse happened to him and there was no justice for his murder: I wouldn’t know how I would deal with that. Putting myself in that family’s shoes just never left me; it’s been in my body since then.”

Martin’s story gave rise to Our Fathers, Sons, Lovers and Little Brothers, an acclaimed full-length work that Simamba brings to Vancouver for the 2022 PuSH International Performing Arts Festival. A coproduction by Tarragon Theatre and Black Theatre Workshop (Canada’s longest-running theatre company dedicated to the works of Black and diasporic communities), and based on the 2019 world premiere produced by b current, the solo show takes place during the first few moments of the afterlife of a 17-year-old Black boy named Slimm. As his calls to God go unanswered, he tries to unravel the truths of his life and his tragic, unchosen death.

Makambe emphasizes that Our Fathers, Sons, Lovers and Little Brothers is not a direct retelling of Martin’s story but rather draws from it, born out of her desire to mourn the youth’s death but also to celebrate his life and the lives of all young Black men.

“This is not a play as much as it is a prayer and a ceremony for me,” says Simamba, who was born in Zambia and raised in Guyana. “I feel like I offer my best self to that intention and to those ancestors and to the story….Black Lives Matter talks a lot about Black deaths, and I understand why that’s necessary. For me as a creator, even in the death of this character who’s inspired by Trayvon Martin, the intention was to remind an audience that that hashtag that people saw, that name, refers to a life, to a body, to flesh and blood and bone and a beating heart and a nervous system and scars they got when they were four years old doing dumb stuff that kids do, as well as a favourite breakfast cereal, as well as a best friend, inside jokes, nicknames they had with a parent… Sometimes I just feel we only ever spend time with Trayvon’s death, or Breonna Taylor’s death. It’s really a reminder for us to remember and humanize the people we see in these headlines.

“I also wanted to hold space and ceremony for my community in the sense that we don’t get to mourn because there’s always the next person to be advocated and marching for,” she adds. “You can’t even catch your breath and there’s another headline, and it’s so overwhelming. I wanted this space to be a place where Black people could come as they are, maybe in a hoodie, since some people tried to demonize Trayvon’s hoodie and make it seem like that was threatening; I want people to come in baggy jeans and a hoodie if they so choose, to know by the way I’m approaching the story—which is for the Black community and for Black young people, first and foremost—that this is a place where we can sit in the reality, honour, and hopefully have some sort of release, a process of understanding, and an opportunity to connect and share.”

Makambe K. Simamba.

Directed by Donna-Michelle St. Bernard, Our Fathers, Sons, Lovers and Little Brothers was developed thoughtfully over several years. Following the establishment of the Trayvon Martin Foundation in 2013 by his parents, Sybrina Fulton and Tracy Martin, Simamba, who studied drama at the University of Lethbridge, tried to write a theatre piece about the Black experience. “But I don’t think I was mature enough as artist or had processed what I needed to to create a piece,” she says.

That changed when she took a three-week theatre-creation intensive at One Yellow Rabbit Theatre in Calgary in 2016. She was simultaneously getting over her first big break-up and coping with immense grief stemming from the death of her cousin, a woman in her early 20s, in a car crash. Although Simamba was tempted to quit the program altogether because she was so deeply sad, she stuck with it—her cousin would have wanted her to—admitting that her goal was simply to finish the course rather than wow anyone. It turned out that not putting pressure on herself was exactly what she needed. Simamba created a 10-minute solo that proved so moving that many viewers were in tears.

“In intensives, it’s common for artists to really want to impress the instructor, especially as an emerging artist,” she says. “I was completely freed of all of that. I just going to make something from that place of grief and impulse, and because of my cousin’s death, I was thinking about afterlife and ancestry. And so somewhere in that storm, I sort of ended up in my body moving and exploring the dance language of Black teenagers from the early 2010s. The Soulja Boy era felt really interesting for me to explore on-stage,” she adds, referring to the American rapper and producer.

Having tapped into a kind of language that spoke to her soul, Simamba says the writing and creative process of the piece grew even deeper after that creative lab. While she says she had a wonderful educational experience at the University of Lethbridge, where she felt supported and was encouraged to write solos, she was also the only African student. It was during the intensive program with One Yellow Rabbit that she began to comprehend the innate powerful force of what came naturally to her.

“As an African woman raised in the Caribbean, the role of the body and movement and dance has been integrated into all of the cultures I grew up in,” she explains. “Anything that’s really physically expressive totally feels like home for me. In my theatre training, the movement I learned was useful and I definitely learned from it, but it wasn’t of my culture, it wasn’t of my people. I quickly realized that my body was carrying information that my classmates’ body wasn’t carrying. We’re all carrying different stories. I slowly began to tap into the body as a safe place and a healing place but also how this body actually carries ancestral information.

“Something that I learned from the lab was permission to craft and create my own practice based on and influenced by the things I liked and things I looked good at,” she explains. “In theatre school, there was no class that was ‘okay, let’s talk about hip hop and how that can be used in storytelling’ or ‘let’s talk about Afro beats and drums and what that does if you play it underneath a Shakespeare piece.’ I started to feel permission to make art out of what you want and pick your own storytelling language, so I started to think, ‘heck, yeah, I’m going to do some dance moves and play Kendrick Lamar. I invited joy into the practice. I felt like I was leaning into impulses of my own body. And also, there are just not that many plays that tell stories of Black teenage boys.”

Makambe K. Simamba in Our Fathers, Sons, Lovers and Little Brothers. Photo by Dahlia Katz.

With Our Fathers, Sons, Lovers and Little Brothers, Simamba hopes to reach that very audience—young Black men who, simply because of their gender and the colour of their skin, are more likely to be the subjects of discrimination and police targeting or violence. Set against a video backdrop, the work draws from rap and hip hop. It’s influenced by Simamba’s travels to Sanford, to see where Martin lived and died; to Ferguson, Missouri, to the very spot where 18-year-old Michael Brown Jr. was shot by a white police officer in 2014; to Montgomery, Alabama, where she spent time at the Rosa Parks Museum; and to Zambia, where she reconnected with her roots. And in revealing aspects of a real life, the show also has moments of lightness and humour.

“I felt very early on it was important for this character first and foremost to speak to people who look like him and were his own age, because they are the future and they’re so smart and we don’t give them enough credit for how smart they are,” Simamba says. “When I was writing, I was really, really clear about the language, the energy, the attitude, the costume, the sound. I think of myself as that lone Black student at the University of Lethbridge, and that was not the only place I’ve had being the only Black person in the room. If I go to a school or if teach a workshop and there’s that one Black student, I always think, ‘How can I let you know that I love you, that you’re incredible?’ How can I pass that on to that 17-year-old for who this might be their first play? My second hope is just to give space to the Black community to mourn or release or just connect, and for the allies in the room to go ‘okay, I get it now’ or ‘there’s something new I’ve learned.’

“My hope is to acknowledge and honour Trayvon Martin as the inspiration for this story,” she says. “I feel like there’s a level of integrity and purpose and consciousness with which I’ve chosen to approach the work. I felt called to bring forth this work in this way—in the same way that a high-school teacher who did not have to put any information about Trayvon Martin in her curriculum still put it in there and thought it was important to talk to kids about was also chosen; the way that dancers have also told the story of Trayvon and let it wash through their bodies also chose it. There’s an energy and a momentum to what that spirit brought to this Earth and left that I feel called by, called to, connected to, and really privileged to be a part of.”

For more information, see PuSh Festival.