In Dani Gal's Historical Records, obscure vinyl collection provides a unique and haunting trip through 20th-century events

Gathered by the artist over two decades, albums eternalize the voices of figures like Lee Harvey Oswald, Atatürk, Diefenbaker, and more than 200 others, at the Polygon Gallery

Historical Records.

The Polygon Gallery presents Historical Records until July 14

STIR BEGINS ITS interview with Dani Gal with a little show and tell. After reaching the artist by Zoom at his home in Berlin, I brandish a weird record I found in New Orleans called Oswald: Self-Portrait in Red. Released in 1964 by a dubious outfit called the Information Council of the Americas, it memorializes a radio interview with Lee Harvey Oswald shortly before his death, the purpose being to posthumously cement his reputation as a Marxist. Gal hungrily scans the artifact, mumbling something about “typical design” as he examines the back cover. Would Self-Portrait in Red make it into Gal’s Historical Records installation, now residing at the Polygon until July 14? It’s a disingenuous question, really.

“It would, absolutely,” he says. “It even could be that I have the same record with a different cover, I’m not sure, but I do have a couple of Oswalds.” He pauses to scrutinize it a little longer. “It’s beautiful.”

It turns out that Gal’s collection does indeed include a version called Lee Harvey Oswald Speaks, reissued by a different label in 1967 and viewable (and listenable) along with the entire collection of some 700-plus records on Gal’s glorious time-sink of a website, www.historical-records.com. “There’s a record that I have in the collection that is all around the Kennedy assassination—The Controversy. The most amazing part in the record is that there’s a short interview with Jack Ruby on his deathbed. This is quite a remarkable recording. He’s almost dead and he’s revealing… some things.”

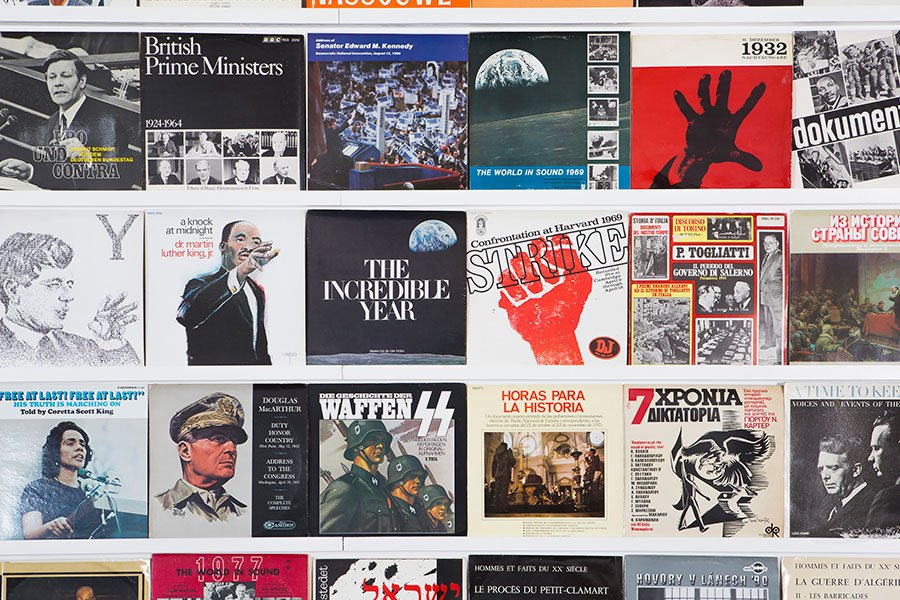

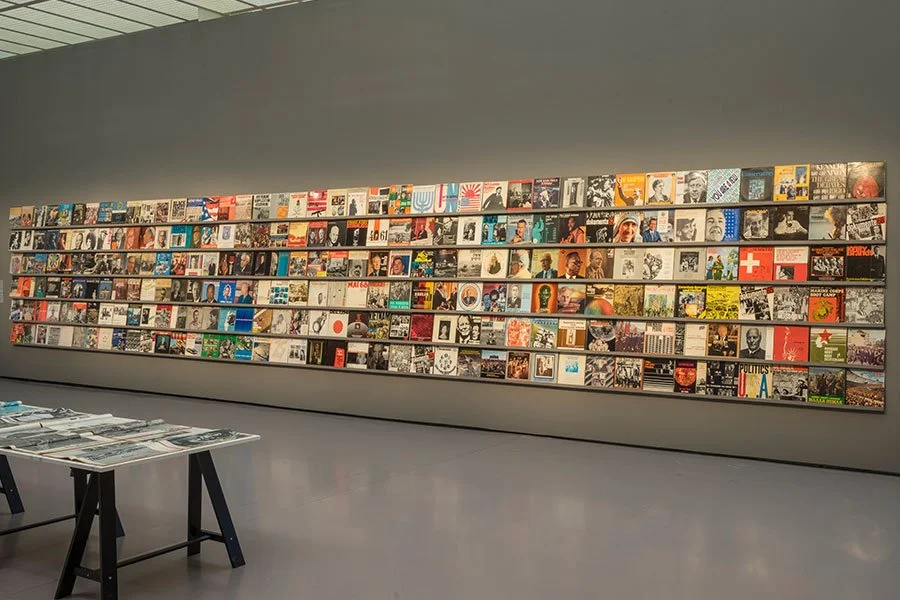

Amounting to what the Polygon bills as an “alternative history painting”, Historical Records Part 1 (on loan from its permanent home at the Migros Museum in Zürich) presents 246—or roughly one-third—of the obscure vinyl albums collected by the artist over the last two decades, composing a unique and haunting inventory of the 20th century’s most prominent events and people.

Visitors are initially confronted with an entire wall of covers, carefully arranged by Gal, while a listening station provides further access to this novel and enlightening peek into the past. If the 21st century is characterized by its slide into a “post-history” digital monoculture, Historical Records is a bracing antidote, reviving perspectives that are otherwise lost on matters ranging from the Moon Landing to the Six-Day War to Watergate.

“The principle of collecting is that the record should have a recording that happened at a certain time, that captured a certain moment in current affairs, if it’s a speech, riots, a war, whatever it is,” says the Israel-born artist, who began his crate-digging in 2005. “Some have some music in them, some are collages, with an insert of a speech or something. There are very small exceptions. For example, the most famous speech by Nelson Mandela, ‘Why Am I Willing to Die?’, it’s not him speaking it, but the record was important enough to be there. And there are some strange things. There is an East German record of a speech by Angela Davis speaking in German in front of East German youth. On the back side is Beethoven’s Fifth.” Gal chuckles. “It’s one of my best records. It’s a completely strange record.”

The installation is, in fact, teeming with strange records and ghostly dispatches from our collective amnesia. Gal reckons that his “most interesting” Canadian entry is Voice of the Pioneer, a 1982 release anthologizing first-person accounts of settler life. Among the myriad implications of the show is the understanding that recording technology itself is wedded to the western colonial project. “When all the philologists and the anthropologists went over to the New World,” remarks Gal, “they called it ‘documenting dying languages’. Obviously those languages didn’t die alone, because there was the whole genocidal process that was going on over there, but it was this excitement of, ‘Let’s catch these voices before they disappear.’”

Dani Gal, Historical Records Part 2, install view at a private office in New York City (2016–2017).

There are other more subtle pleasures to be derived from Historical Records. These are fetish objects retrieved from a strange and woolly grey marketplace, whose purpose and value can only be guessed at. “I could go to a thrift store and buy a record like you’re holding for one dollar, and I could go to a second-hand record store in New York, and the same record will be 150 dollars, right?” says Gal. “So some of them have this value. I was in a store in New York and I bought a record of the Eichmann trial for 150 dollars. I was like, ‘I have to have it. There’s no way I’m not gonna have it.’”

Early in the process, Gal was at the Istanbul Biennial when a colleague nicked his mother’s copy of Gal’s sole Turkish album: two sides of speech by the first President of Turkey, Mustafa Kemal Atatürk, released in 1965. “It sits in someone’s living room for years and years. You have no idea how it got there and why. And then it becomes part of the collection,” he says. “This is very special to me. But this is also in a way the core point in my interest in it, because to think of a record like this, in someone’s home: what is the motivation to replay a history record on your system at home, as you would play music. What is the joy there? Where is the joy? And I really like this moment where the personal meets the collective narrative.”

Concurrent to this is a thrilling metaphysical angle to Historical Records, discussed in a conversation with producer-journalist Marcus Gammel on Gal’s website that touches on spiritism and the parapsychological. Even the most rational among us can’t deny the spectral resonance of the recorded voice and its curious advantage over the moving image. It’s an idea that visibly excites the artist, who made a film in 2010 about the very spookiest of recording artists, legendary Jamaican producer/trickster Lee “Scratch” Perry.

“What I find interesting in the phenomenon of sound, what you talk about as ‘ghosts’, is there’s an ephemerality of the sound that is in a way kept in a medium, but once you play it, it comes back to the room. Film is always framed by the screen, so in a way you’re always in a safe space from it, it’s over there. Sound is a spatial medium. It’s a sculpture. In an abstract way, it can be thought about as sculpture. It does exist in the room. It is material moving in the room. Once you play it, and then relate it to these historical events, it is now coming back to the room. On a certain level of your consciousness it is there.”

In contemplating Historical Records, Gal invites us to imprint our own “joy” on these unloved relics. When Part 3 of the collection was moved last spring to Paris’s Centre Pompidou, Gal was delighted to witness the “awe” with which museum workers beheld a record of the lionized French novelist and culture minister André Malraux. Offering yet another perspective on this delightful show, we could consider how our current political “class” compares to the statesmen and public figures of the 20th century. Gal’s partner hails from Comox, and on one of his frequent trips to Canada’s West Coast (where he makes regular visits to Neptoon Records on Main Street) he was jazzed to score a copy of a 1976 release called Diefenbaker in Delta.

“I think it’s the last record I ever bought,” he says. “I was on the main island in a thrift store, five bucks, and it was never opened. What’s interesting about the whole collecting thing is that you find a mint, never opened, sealed record that was printed in the ’60s or the ’70s, no one is interested, you know? Finding this weird Diefenbaker in Delta—who cares, right? But it’s a nice record, cause he was a funny guy.”

In his interview with Gammel, Gal refers to another recorded conversation from another time, between Warhol acolyte Gerard Malanga and William Burroughs. Pointing to the tape deck sitting between them, Burroughs remarks: “The only evidence that this conversation ever took place here is the recording, and if those recordings were altered, then that would be the only record. The past only exists in some record of it. There are no actual facts.” In the end, each of the artifacts in Gal’s show is a work of subjective history, and this is the final irony implied by the name. When visiting Historical Records, we are being compelled by someone to believe that Diefenbaker was a funny guy, and maybe he was, and that Lee Harvey Oswald was a Marxist, and maybe he wasn’t. ![]()

Dani Gal, Historical Records Part 1, install view from The Future of History at Kunsthaus Zürich in Switzerland (2015).