U.K. dance artist Hofesh Shechter's two-part Double Murder journeys from darkness to hope

In the choreographer’s much-anticipated return to DanceHouse, Clowns explores the urge to violence as entertainment, while The Fix is a moving tribute to human connection

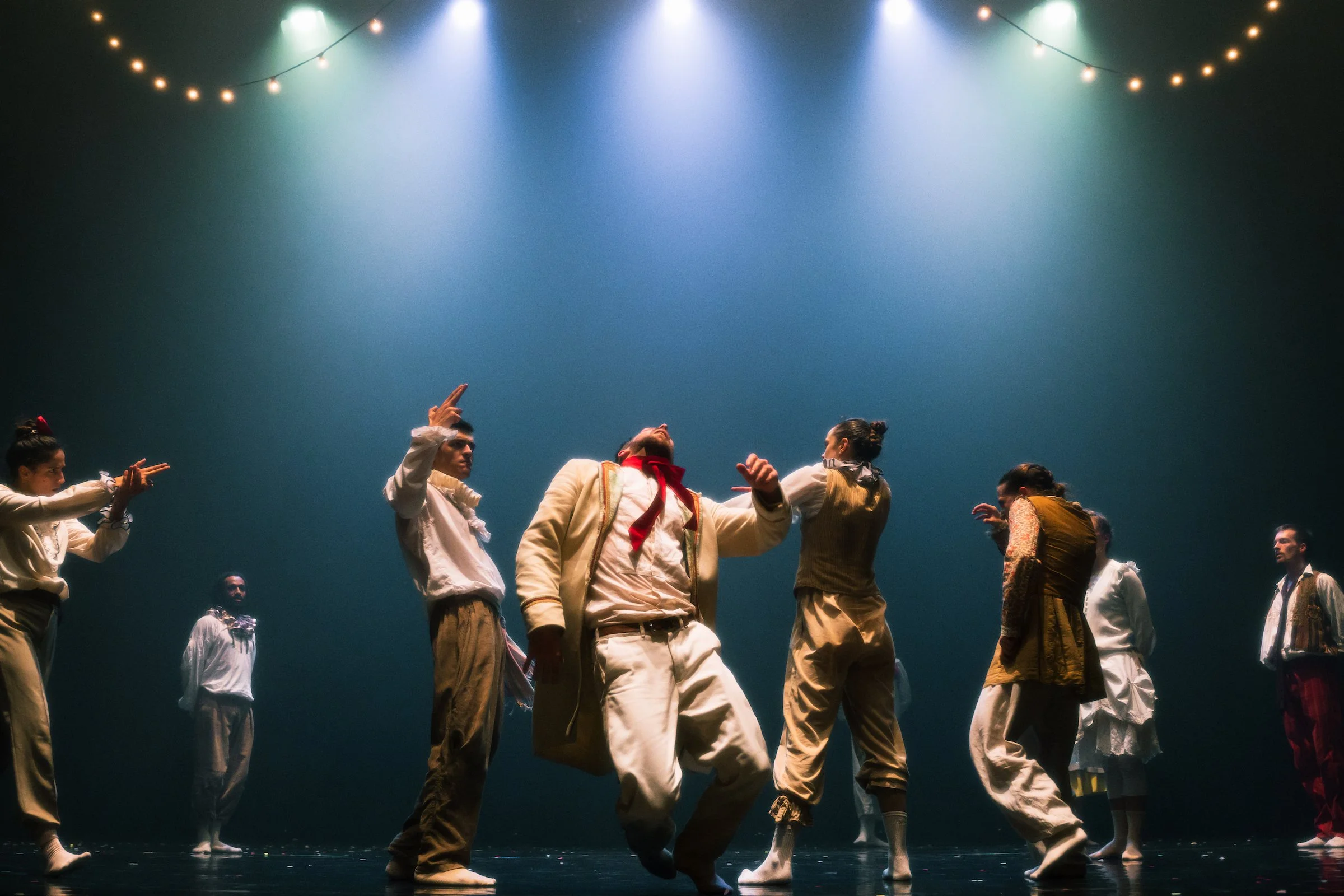

Hofesh Shechter Company’s The Fix, from Double Murder. Photo by Todd MacDonald

Hofesh Shechter Company’s Clowns, from Double Murder. Photo by Todd MacDonald

DanceHouse presents Double Murder at the Vancouver Playhouse on October 21 and 22

WITH CLOWNS, CELEBRATED contemporary dance artist Hofesh Shechter created a work so dark that he felt he needed an “antidote” in the form of a second piece.

The result is a two-part program called Double Murder—featuring Clowns and The Fix—which comes to Vancouver October 21 and 22. The combination allows the Israeli-born, Batsheva-trained, London-based choreographer to give fans the raw intensity they’ve come to love, but also to reveal a new side to himself in this long-awaited return to DanceHouse.

“Clowns was performed separately at first, and once I saw it over and over, I thought, ‘That’s so depressing,’” the self-effacing international star of the dance world tells Stir over the phone from London. “There was something so hopeless about it; it’s so sarcastic, so painful. And my one thought was, ‘I want to give it an answer; I want to put another option on the stage. I don't want to agree or accept that that's the only option!’ I thought, ‘Clowns is a lens to see the world through, but there are other lenses.’”

Clowns’ fiercely sardonic vibe won’t come as a complete shock for audiences who have taken in works like barbarians or the tribal-animal Uprising on his company’s past visits to DanceHouse. Yet Clowns is a deeper shade of black: the titular characters gleefully play a game of murder one-upmanship on each other, in acts geared clearly to entertain—a scathing comment on society’s numbness to carnage.

Shechter originally created the piece for Nederlands Dans Theater, calling it “a simple idea that I was curious about, and I didn’t really know where it was going.”

“I thought about entertainment—and what entertains audiences when you think about Hollywood is violence,” Shechter says. “We started this game in the studio and it got some momentum; I felt like the performers are trying to get attention by any means.

“We were laughing a lot in the studio doing it—which sounds horrible!,” he adds. “But I thought it’s really ridiculous to choreograph killing, doing it in unison. It was incredibly entertaining, but then it just became a nightmare that won't stop. And I found that a very powerful experience in the studio. I find clowns incredibly entertaining, so it's a fun piece in a way, but it’s also very disturbing and that dichotomy in a way just gives it power.”

When Shechter decided to create its antithesis in The Fix, the process could not have been more different. And the result feels eerily prescient, considering Shechter made it just before the pandemic hit.

Wanting to escape the distractions of busy London, he isolated himself with seven dancers in a tiny Italian village to work on the more intimate creation.

“Working there we felt incredibly cut off from the world,” he recalls. “Time kind of stopped for us. What shaped a lot of the piece was that I was trying to discover with the dancers: What is the most precious currency of our time? I wasn’t talking about money or gold, but human currency. What can we give people on stage?”

Through conversations with his dancers, Shechter focused on two key gifts they could offer through the work: hope and time, the latter because “we live in a place where we never have time.”

“We started with how the group behaved within itself, with a lot of attention and care to each other, trying to make it work altogether for each other, and building a Utopian world,” he says. “So it was really interesting for me to try to create a chain of events and emotions and imagery that perhaps brings us to a place that is hopeful.

“And maybe at the end of the evening we will forget about Clowns,” he adds with a small laugh.

Shechter, a percussionist who always creates his own soundtracks, sought to do something unique with the music this time out. Using a loop machine, he composed a score that would continually morph, evoking a timeless feel. As usual, he wrote the music at the same time as he worked on the choreography: “It’s as messy as you can imagine,” he says with another laugh. “There’s no real system other than I am working for it to happen, trying different sound, then trying it in the studio, then taking it home and coming up with more sound, and trying it with the dancers again.”

After two years of social distancing, Shechter is struck by the close contact and intimacy of the work—as he calls it, “the community feel of it, the kind of a buzzing mash of people”.

Hofesh Shechter

“It was for me such a moving piece to see post-COVID, to see people so close together, touching and helping each other,” he reflects. “I’m normally incredibly skeptical about my work. But The Fix is one of these pieces where I just love sitting with an audience and watching them experience it. It’s just pure joy.”

For those who are familiar with Shechter’s biting work, “pure joy” will be a departure. The dance disruptor agrees that The Fix is different for him—in ways that are less immediately obvious.

“I felt that one of my—to call it shamelessly—‘tools’ is normally taking time away from the audience,” he says. “It’s happening quicker than what your mind and your feelings can take. You have to watch because it is ahead of you all the time, which is something I love.

“But with The Fix I thought, ‘I want to give time back to the audience now. I want to find the same intensity not by taking time away, but by giving time to the audience.’”

Take all of this as a sign that Shechter is in a rich creative period at this point in his career—a word that he says scares him, by the way. It shouldn’t. After dancing at the renowned Batsheva Dance Company, Shechter moved to London in 2002, and when he won the 2004 Place Prize’s audience award for his sextet Cult, he saw his career take off on a meteoric rise; he formed his own company in 2008, toured the world, and created pieces for top-tier troupes like New York’s Cedar Lake Contemporary Ballet and London’s Royal Ballet. But looking back at that decade, he says he felt “G-force pressure”.

“I had to deal with a lot and digest a lot, and now I just feel like I'm living my life,” he reflects, adding that he still spends a lot of time outside of dance, just making music.

On the day Stir reaches him, Shechter is creating a new solo in a studio in London, and is preparing to head to Stuttgart to make a short film with a dance company. The in-demand artist reports being in a happy place, thrilled to be able to work with his hand-picked team of top dancers from around the globe.

At this point, Shechter appears to be honing, and growing more assured with, his singular voice—a kind of “total” theatre driven by atmospheric music and cinematic-style edits and jump cuts. That vision, as ever, is rooted in staying true to himself—no matter what “G-forces” are at work on the outside.

“I imagine myself in a theatre and ask, ‘What do I want that would happen? What would really excite me? What would be really awkward? What can I imagine that would be really beautiful?’” he says. “The only judge that I have in my head is me—and my instincts.

“Cinema is telling a story and taking us on a journey, and for me, for a contemporary dance performance to take the audience through a journey is not a bad thing. It's not a cheap thing. It's the truth that I want to make work that makes people feel things, and go through emotions—and that makes me feel like they're sharing it with me. I cannot connect with works that are so obscure and abstract. I love that people can feel things that relate to their life.”

Clowns. Photo by Todd MacDonald