VIFF opener Monkey Beach was a decade-plus labour of love for director Loretta Todd

The B.C. filmmaker aims to capture the magic of Kitamaat and Indigenous lore of Eden Robinson’s book

Grace Dove plays a woman who returns to Kitamaat from the city in Monkey Beach. Photo by Ricardo Hubbs

Streams September 24 to October 7 as part of the Vancouver International Film Festival, via VIFF.org and at the Vancity Theatre (6 and 9:30 p.m.), Cinematheque (6:30 p.m.), and the Rio (6:30 p.m.)

MORE THAN A decade ago, when Cree-Metis director Loretta Todd first set out to turn the book Monkey Beach into a film, she knew it would have to be shot on location in Kitamaat.

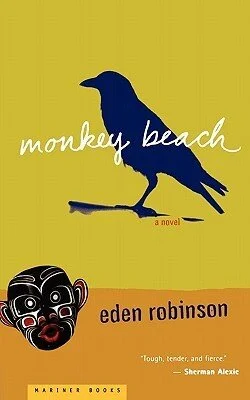

Eden Robinson’s popular 2000 novel is, after all, firmly rooted in the Haisla territory perched between lush forests and the waters of the Douglas Channel.

“Indigenous knowledge systems and Indigenous story come from place, and Indigenous science flows from place,” Todd tells Stir before her atmospheric feature opens this year’s mostly virtual Vancouver International Film Festival. “When we say ‘all my relations’, we’re saying, ’I have a relationship to all the beings in my territory, and to the plants and to the rocks.’

“That’s Eden’s place,” she stresses. “I can never be a Haisla; I can never claim to be a Haisla. All I can do is be in that place.”

The Monkey Beach shoot often relied on local boats and the people who fish off Kitamaat. Photo by Ricardo Hubbs

Director Loretta Todd spent a more than a decade trying to get Monkey Beach made.

Making those journeys over the years she tried to get the film made had a profound impact on the Indigenous filmmaker. “There was a part of me, going through those lands that are so rich with history, thinking of all of the people here and all of the wealth taken out of here.”

The result is a film that also takes us to that place--amid its towering conifers, out on its rough waves, and along its windswept shores.

The film’s majestic landscape suits the epic tale. Infused with Haida mysticism and supernatural characters, the story goes back and forth from the rebellious teen Lisa (The Revenant’s Grace Dove) trying to solve the mystery of her brother Jimmy (Joel Oulette) going missing at sea, to the past and the profound moments she had as a child growing up on the Kitamaat reserve. The subject matter touches on the uplifting lessons from Ma-ma-oo (Haisla for "grandmother", brought to life by Tina Lameman) to the enduring trauma of residential schools. Along the way, Lisa is haunted by premonitions and meets ghosts, shapeshifters, and a symbolic crow from Haisla lore--a power she has to learn to accept, just as she learns to re-embrace her traditional culture.

Monkey Beach weaves in the supernatural. Photo by Ricardo Hubbs

The connection between a book, a filmmaker, and the land

The innovative, genre-busting novel was nominated for the Governor-General’s Award and the Giller Prize, and is still a mainstay on both high-school and university curricula around the world.

Todd was introduced to Monkey Beach in the early aughts, when an acquaintance suggested she read it because there was an affinity between Robinson’s writing and her filmmaking. The director was surprised to find her own name acknowledged as an influence in the credits of the book; she had never met Robinson at that point.

“Monkey Beach is just so visual--it just lends itself to cinema but it’s so complicated because she shifts time so much,” Todd reflects. “It was always important to me to reflect Eden’s storytelling. She’s a genius, but it also flows from Haisla storytelling and Indigenous storytelling--it just flows and you don't really know where you’re going. This whole three-act thing is a construction.”

That flow is something Todd expresses visually as well. Monkey Beach marks her first full-length feature, after a long career primarily focused on groundbreaking documentaries like Hands of History and Forgotten Warriors. And here, the camera moves through the space in an almost spiritual way. Hypnotic drone footage often sweeps over the forest to the village and docks and out above the green-blue inlet.

“I was very conscious when I was watching documentaries growing up of how there was always that ethnographer gaze from outside the community,” Todd explains. “That gaze was how we were always portrayed--and I was very conscious of that static camera. So when I made documentaries, I always wanted a camera that flowed through space.

“It was hard in the beginning--there wasn’t a lot of money, and it was usually a pretty modest budget,” she recalls with a laugh, “and it wasn't easy to get dollies and steady cams. So movement has always been really critical to me. What does occupying space look like? How do we put ourselves on the land?”

Left to right, Monkey Beach director Loretta Sarah Todd, actor Grace Dove, and author Eden Robinson. Photo by Ricardo Hubbs

Snotty Nose Rez Kids, Jesse Zubot pitched in

As much as that flowing camera work marks the film as Todd’s, so does a soundtrack that’s as cool as it is haunting: local musician and composer Jesse Zubot not only lends his atmospheric strains to the soundtrack, but an off-the-hook array of Indigenous musicians, including cello innovator Cris Derksen, powerhouse singer-songwriter iskwē, and hip-hop duo Mob Bounce. Kitamaat-born Snotty Nose Rez Kids also make an unforgettable appearance losing their shit at an epic bush-party banger.

“I'm always looking for unique and interesting music--it’s my inspiration in a way,” says Todd, who’s featured the likes of Mob Bounce and DJ Kookum in her Coyote Science kids show on APTN and CBC Gem. “I’m always looking to support our people and looking to show who they are and what they do.”

In the same way, Todd wanted to support emerging artists in her cast and crew--and in the community where she made her film. Shooting a movie so tied to the land requires the help of the people who know it best.

“We felt very welcomed by the Haisla nation, and I was adamant that we hire as many people as we could from the community,” Todd says, adding her crew moved right into a real family home on the coast to use as the main set. “We hired a lot of the women in Kitamaat to work on location--some had to be the first ones there and the last ones to leave. And we hired a lot of boats: we had to rely on the knowledge of the oceans, the knowledge of the tides--they had fished there since they were kids.”

Eden Robinson’s Monkey Beach still sits on school curriculums.

That kind of care and connection has come from years of nurturing a project that’s been challenging not just because it’s based on a beloved book that shifts between times and realities. It’s also that Todd has carried an extra responsibility in telling Indigenous stories--right since the beginning of her career, an era when they were even rarer onscreen than they are now.

“I remember from when I first started making films, someone told me, ‘These stories don't belong to you they belong to future generations,’” she explains. “What will the legacy be and how will they influence future generations? I’m always conscious of that: How can I make a film dealing with these heavy issues but yet at the end people watching it feel stronger?”

All that effort seems to have been paid back by the forces that watch over the Haisla lands at the head of Douglas Channel. Unable to secure funding to head to Kitamaat in August, the crew had to risk filming in September, when the rains normally hit the region--one of B.C.’s wettest. Locals could hardly believe the sun shone for almost the entire stretch of making Monkey Beach. Even the area’s grizzlies kept their distance for scenes in the deeper wilderness.

“Some said we’d been blessed by the ancestors looking out for the shoot,” Todd says.”