Listener meets flutist: Music on Main's one-on-one concerts provide a brief respite from apocalyptic times

A gift to arts fans, “As dreams are made” reinforces our need to connect—and to breathe—in the COVID era.

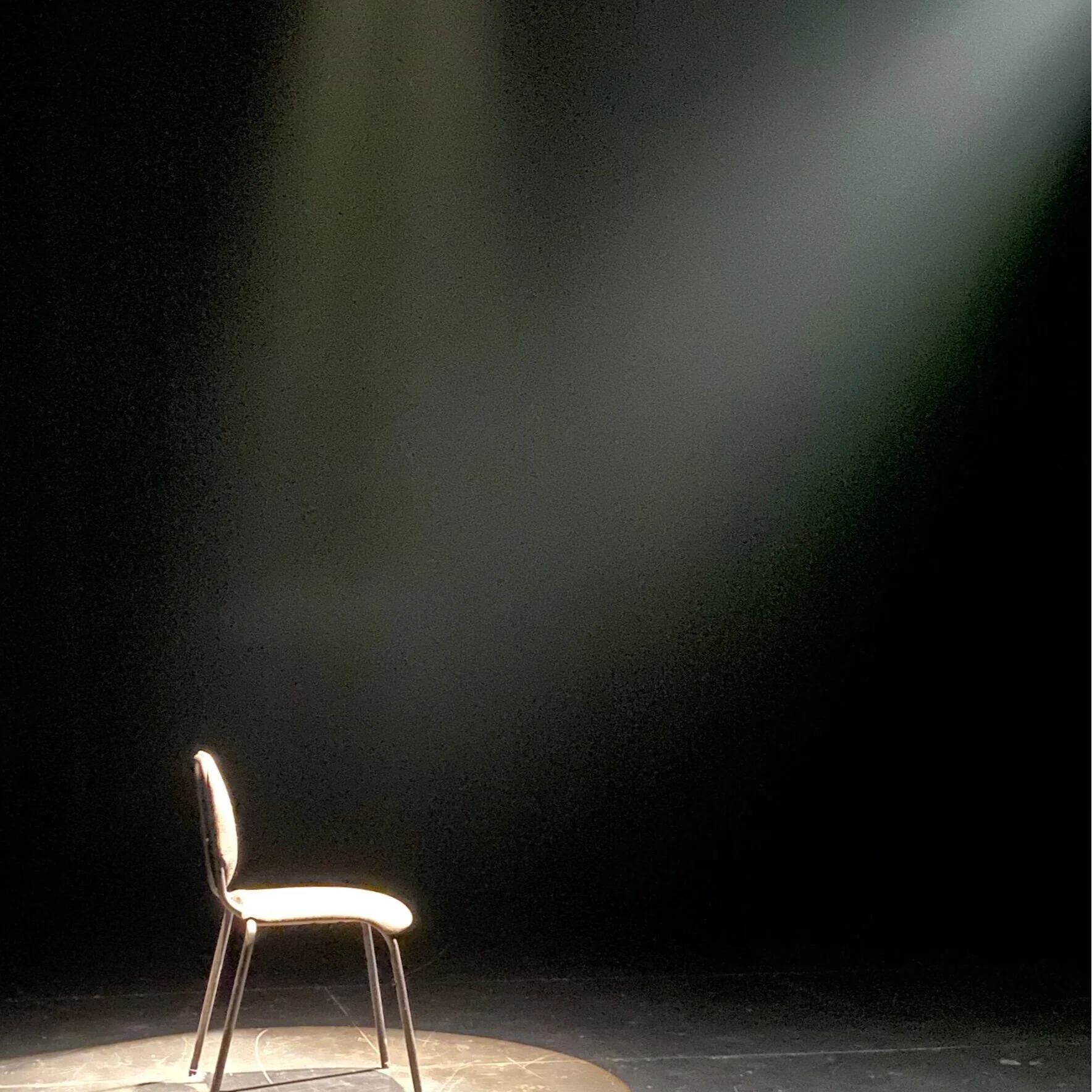

A chair awaits a single audience member in the Vancity Culture Lab. Photo courtesy Music on Main

Music on Main remounts “As dream are made” from October 6 to 11.

OUTSIDE THE DOORS of the Cultch, things are unsettlingly Biblical. The sky is tinged an angry orange from coastal forest-fire smoke, western hemlock looper moths are making curlicues in the air, and the residents of East Van shuffle by in hospital masks. There’s an out-of-body sense of unreality about these COVID-19-plagued times.

I’m waiting here to experience As dreams are made—Music on Main artistic director David Pay’s response to the pandemic. A concert made up of precisely one listener and one surprise musician, it’s his gift to arts lovers: a respite from Mothpocalypse and other mounting stresses of the outside world. If only for 15 minutes.

First, some background. The program was inspired by 1:1 Concerts, a project by the members of two orchestras in Stuttgart, Germany. The goal is to provide short, wordless, socially distanced encounters between an artist and newfound fan, often outside, in nontraditional settings. The idea has spread its way around the world, with one-on-one performances now happening in England, the U.S., Switzerland, and France.

But As dreams are made is also very much a creation of Music on Main, a company devoted to inventive presentations of top-flight contemporary music. The project will feed into The Tempest Project, a full-length immersive work the organization intends to premiere in 2023. For the current, much more intimate, experiment, Pay and his team have heightened the one-on-one concert by adding Katie Findlay’s recorded reading of some of Prospero’s most famous lines from The Tempest, as well as Adrian Muir’s lighting.

After entering the Cultch, and then slathering on hand sani and filling out the by-now-familiar forms about being symptom-free, you’re guided to the door of the small Culture Lab space. There, you’re given instructions about entering the black-box theatre—alone, except for the unknown musician who will be seated three metres from you. You have to wear a mask to go in, but you’re allowed to take it off once seated. After entering the dark void, you see it: an empty chair lit by a spotlight.

Seconds later I’m sitting across from the spectacular Vancouver flutist Mark Takeshi McGregor. He sits silently holding his instrument, and making direct eye contact across the socially distanced space between us. This is neither awkward nor unsettling. The feeling of connection is something that’s hard to describe; it’s something closer to comfort and mutual empathy.

Mark Takeshi McGregor plays for a visitor. Photo by Jan Gates.

Mark Takeshi McGregor. Photo by Jan Gates

Rather than oppressive, the darkness feels like it’s insulating us against the world.

We sit in silence, taking in each other’s presence, and then the virtuoso chooses the piece he will play. McGregor throws himself into Bach’s technically demanding Partita in A Minor. The close proximity drives home the fact that McGregor’s flute playing is incredibly physical. His entire body leans into the punishing runs and expressive rubatos, pulling back to draw out the dramatic high “A”. At times it sounds like he’s channelling several voices at once.

From three metres away, you can appreciate the intricate breath work of flute-playing that can get lost watching a chamber orchestra on stage. In a world where a deadly virus is aerosolized, respiration is a dangerous act right now. How many times have you held your breath passing someone who’s come too close in the Safeway aisle—even while wearing a mask? Breathing is now associated with the way COVID-19 spreads, and yet here, McGregor recasts it as an act as naturally expressive as singing itself. It’s mesmerizing. (Word has it santour player Saina Khaledi and cellist Rebecca Wenham were equally transcendant during As dreams are made this week. It’s just that there seemed to be added resonance that fate would put me three metres away from a musician blowing his heart out.)

The performance gives way to silence again, and then the sound of Findlay reading Prospero’s key words from The Tempest—including “We are such stuff/As dreams are made on; and our little life/Is rounded with sleep.” In this context, the lines make you think of the magic of music, and the dreamlike experience of watching it—especially in this strange, ethereal void. Yes, Shakespeare is reminding us of our mortality—just like COVID and climate change outside the theatre are. But in this context, the words take on a more encouraging and life-affirming tinge.

The effect of the elements put together—the genius of Bach, the virtuosity of the musician, the poetry of Shakespeare—is profound in the least showy way. The overriding feeling? Peace.

As I emerge into the acrid air again, a moth descends from the Cultch awning and lands stupidly in my hair. Did I just imagine what happened inside? Or is it more like I’m wishing that the aura of calm in the Culture Lab was my reality right now—and that the outside world is a nightmare we’ll all wake up from soon?