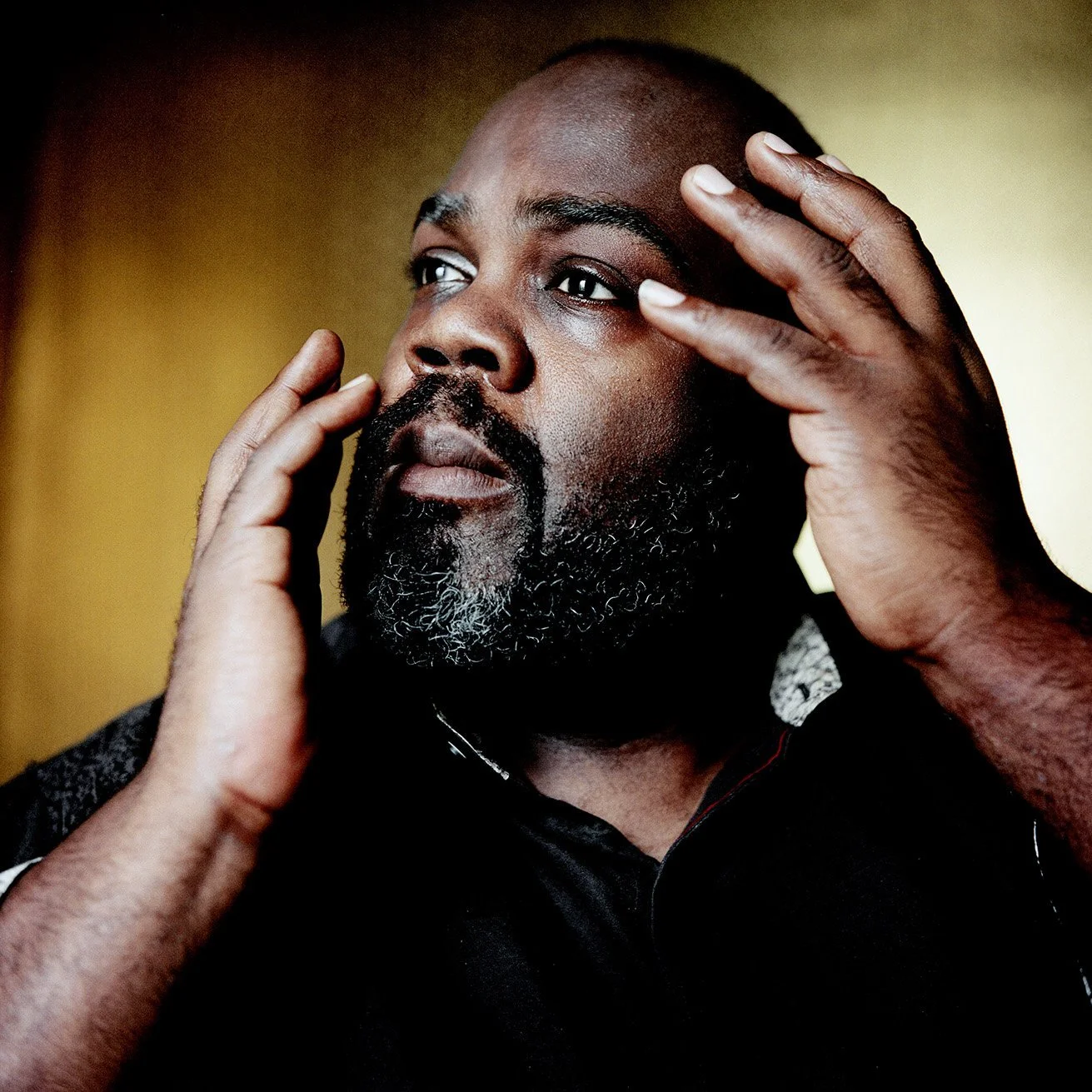

Acclaimed countertenor Reginald Mobley finds his freedom in the higher registers of Baroque music

He bookends his Early Music Vancouver concert Raise, raise the voice with Purcell and Ellington

Nominated for a Grammy for his work against the whitewashing of early music, countertenor Reginald Mobley sees himself as a beacon to others.

Early Music Vancouver presents Raise, raise the voice: Reginald Mobley at Christ Church Cathedral at 7:30 pm on February 3

FOR CELEBRATED AMERICAN COUNTERTENOR Reginald Mobley, everything in his life is about freedom these days.

That shows when he mixes music on a program: look no further than this weekend’s Raise, raise the voice concert with Early Music Vancouver, where he bookends the show with Henry Purcell and Duke Ellington. It also shows in the ways he breaks down preconceptions about class, sexuality, and race when it comes to early music roles.

“I love that freedom to be who you are: singing who you are and being who you are,” the Boston-based activist and artist tells Stir over the phone before his concert, which celebrates Black History Month on February 3.

The word freedom goes right back to the way Mobley became a countertenor—a high-register Baroque singing part that he makes effortlessly luminous (see the video at bottom for a taste of his singular magic).

By now, that origin story is well known in early-music circles. In 1998, he was a 22-year-old studying to be a tenor at the University of Florida. One day, he was fooling around, singing the alto top lines of a barber-shop-quartet number, when a professor grabbed him and took him to a piano to sing an octave higher than the tenor range. That instructor then predicted that Mobley would spend the rest of his life singing as a countertenor—which the singer has gone on to do. Earning accolades from Leipzig to San Diego, he’s nominated for a Grammy Award this year.

“When I was told I had this potential to be that, I was so excited,” he relates. “It was ‘Oh!’ Everything snapped into focus. It was like the ugly duckling: ‘Oh, I fit in here.’ It was like dropping 80-pound weights and I could now fly.”

When Mobley turned his full attention to becoming a countertenor, he immediately found himself drawn to Baroque music—the exquisite realm of Bach, Handel, and Purcell.

It all felt natural, especially that form’s emphasis on improvised ornamentation and individual emotion.

“I grew up in gospel and jazz, and that was all I was able to listen to at home, so there was a natural affinity—not just with improvisation but also to close adherence to the rhetoric, or the text,” Mobley explains, “and really working to make that what you sing illustrates the text. The music should organically synch with the words. That was something Ella Fitzgerald did, and that’s what a lot of baroque singers do, so it was a very natural transition.”

Did Mobley stand out in this new early-music milieu? Of course. But no more than the Gainesville-raised artist says he stood out growing up in the Deep South going to libraries and galleries and other supposed bastions of the straight, white upper class.

“There's a huge gap in diversity in early music, more than in any other classical music genre, and obviously I work to be a beacon; to be a lighthouse for other people to find their way to it; to show it's not elitist,” he says matter-of-factly. “It's essentially more accessible for every person than I think a lot of modern classical music is. It’s extremely tonal, extremely relevant; it has so many themes that speak to how we live and feel now. And so it's very important for me to try to be a spokesperson to the people who are just kind of casually interested in music.”

Mobley is aware there are preconceived ideas about what a countertenor should look like, as well. Articles around the world inevitably contrast Mobley’s resemblance to everything from a refrigerator to a quarterback with the fact that he sings like an angel.

“As a luxury-sized vehicle, there is always this notion that countertenors are slight figures,” he says. “I'm an open book on this. There's always someone who might be going through the same thing and needs to know there's someone that understands.”

And so Mobley quietly and confidently pushes forward, raising his voice on issues of race and prejudice. His 2023 Grammy nomination is for American Originals: A New World, A New Canon, a deeply personal project that fights the whitewashing of classical music. It features vocal and instrumental works by unknown composers of colour, diligently collected from across the Americas and dating from the Baroque to the 20th century. (He performs it with the Agave Baroque ensemble.)

Pacific Baroque Orchestra’s Alexander Weimann with Reginald Mobley.

The artist’s work takes him around the world, where he’s comfortable in his own company and enjoys the—here’s that word again—freedom that solitude offers. One of his favourite times in his life was a pre-countertenor stint living in Japan and singing at Tokyo Disney, where he could take a day off, hop on a train, and discover a new hidden shrine or temple.

“I’m a natural loner and extremely introverted,” he says. “I’m very nomadic. I tell people that wherever I lay my head is home—just like wherever I apply my voice is home.

“I accept that humans are kind of social creatures and I accept that singers are supposed to be extroverted and very outgoing,” he continues candidly. “But I’ve always been comfortable in my own mind: at 45 years old I'm still an avid and very active daydreamer. Maybe because I grew up with asthma: I was a pretty sick kid, so I did spend a lot of time indoors. And I just found worlds that were inaccessible to a person, to a Black kid from north-central Florida. I’d sit with my grandmother’s encyclopedia, or I’d just read about mythology. I was always reading stories and I could just visualize these worlds”

That’s why he enjoys singing Purcell’s O, Solitude, at the beginning of the upcoming EMV program with the Pacific Baroque Orchestra. “It’s like the national anthem for introverts,” he says with a laugh. “It gives you the chance to explore yourself and find out who you are.”

He loves pairing that piece with one from three centuries later: Ellington’s “(In My) Solitude”, which closes the program.

“Solitude can be a double-edged sword,” he says. “It’s kind of lamenting the loneliness, the fear of being left alone with your own thoughts—that kind of extrovert’s nightmare of being alone.”

In between those two pieces, expect a program of delicately ornamented and deeply felt Bach, Purcell, and Handel—all the songs carefully chosen and grouped, “raising the voice” in honour of music, divinity, nature, and love.

Every piece revels in Mobley’s joy onstage, singing in a world he sees as wide-open to him. “I never spend any time wondering if I should,” he says. “I will never see those barriers again.”