Film review: Truman & Tennessee: An Intimate Conversation paints a portrait of a friendship in the writers' own sharp-tongued words

The trailblazing artists’ colourful insights on each other, and themselves, will please film, lit, and theatre fans

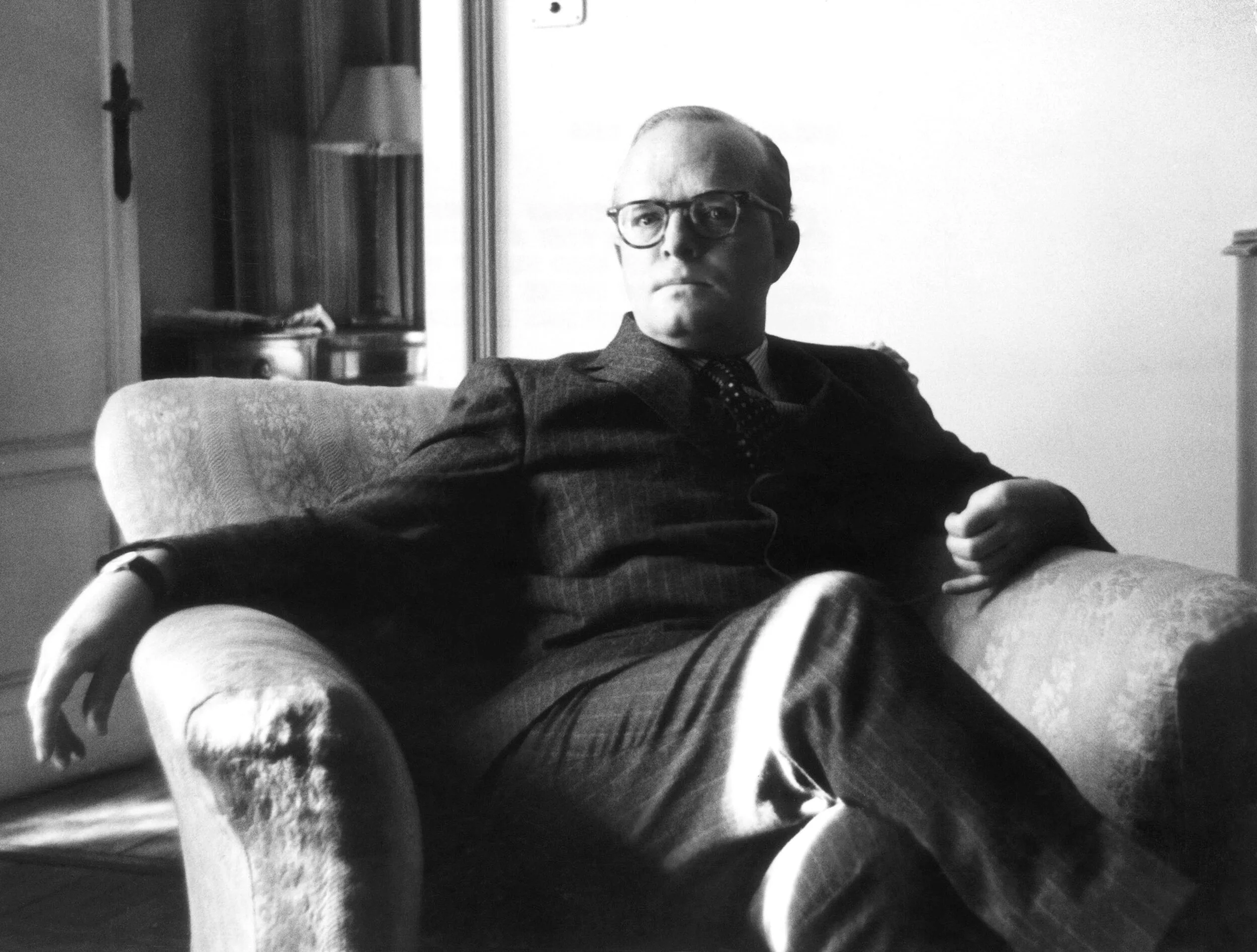

Truman Capote in Truman & Tennessee: An Intimate Conversation. Courtesy Getty Images

Tennessee Williams in Truman & Tennessee: An Intimate Conversation. Courtesy Getty Images

VIFF Connect streams Truman & Tennessee: An Intimate Conversation from June 18 to July 15

FEW WRITERS have ever been as wittily self-aware as Tennessee Williams and Truman Capote, but they shared such a long and colourful past together that they often seemed to know each other just as well as they knew themselves.

That comes across compellingly in Lisa Immordino Vreeland’s new documentary Truman & Tennessee: An Intimate Conversation, in which she deftly interperses their writing and interviews over archival footage, photographs, and clips from the famous movies made from the pair’s works. The approach could have been dry and conventional, but the artists’ sharp tongues, sense of humour, and ability with words bring rich and acerbic new insights into their own and each other’s works. (In voice-overs, Jim Parsons reads Capote’s words, Zachary Quinto Williams’s.)

Film, theatre, and lit fans are richly rewarded. You’ll hear in their own words, say, what Capote thought of Audrey Hepburn as Holly Golightly, or the real-life trauma reflected in Williams’s Suddenly, Last Summer.

The film begins as the two Deep South writers meet, Capote only 16 and Williams 13 years his senior. (“He was adorable,” Williams recalls.) They will remain close for the rest of their lives—though never romantically or sexually—through artistic struggle, fame and fortune, travelling the world together, and struggling with addiction later in life. (Both became patients of the infamous Dr. Feelgood.)

Williams and Capote share painful recollections of growing up queer in the Deep South, bullied in the schoolyard and returning home to troubled families. Williams, especially, is achingly candid about himself and his work. “I feel that I am both Stanley and Blanche,” he allows at one point. His relationship with his own sexuality is a source of both pain and pleasure. “I ache with desires that are never quite met,” he writes. Both men come across as trailblazers, unapologetically gay at a time when that was still taboo.

But what becomes most compelling is how the two men differ—and their own insights on that. Capote sees Williams as a compulsive writer, superstitious to the point of mania, and nagged by his longtime partner. Ever self-aware, Williams cops to being jealous, never more so than when Capote draws a rave review for his first play. “Capote is a liar, and everyone knows he is,” Williams asserts. He also aims a few sharp barbs at Capote’s taste for fame and celebrity. And compare the different ways the two writers answer David Frost’s probing questions about love and sex, in TV-interview clips adeptly played off each other here by Vreeland.

What the filmmaker builds feels like a true conversation between two men who we never see actually talking to each other. And while Capote and Williams display their share of bitterness--both would call it "bitchiness"--toward each other, this is ultimately a moving and empathetic portrait of two complex frenemies navigating an oppressive time together.