Copy Machine Manifestos traces zine culture, stitching together niche networks from the 1960s to today

Exhibition captures a raucous “multitude of voices” and work by names like Raymond Pettibon and K8 Hardy at Vancouver Art Gallery

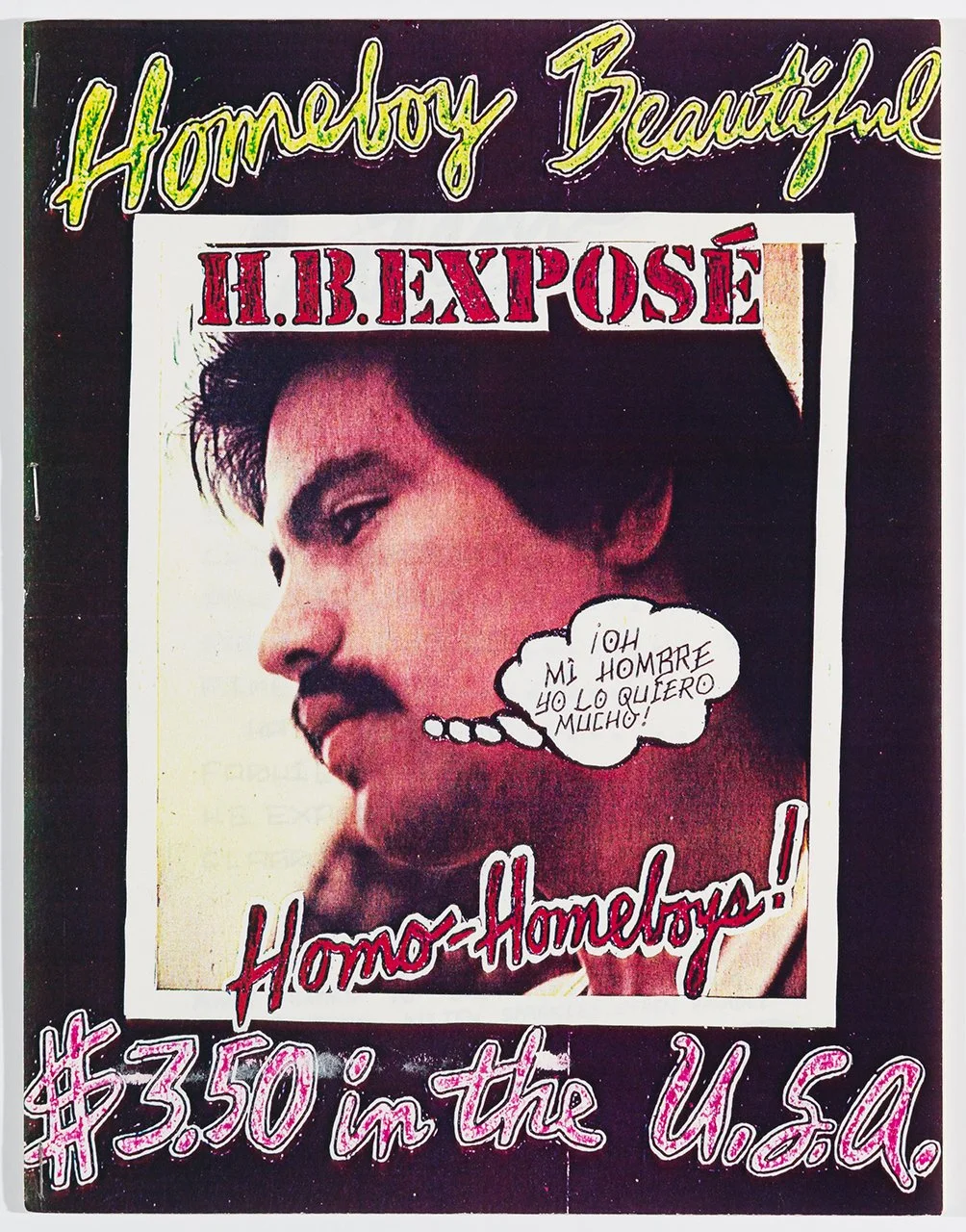

Joey Terrill’s Homeboy Beautiful, no. 1, 1978, photocopy zine, ONE Archives at the USC Libraries, © courtesy Joey Terrill and Ortuzar Projects, New York.

K8 Hardy’s Envelope Quilt, installation view at the Vancouver Art Gallery.

Vancouver Art Gallery presents Copy Machine Manifestos to September 22

WHETHER THEY’RE vegan bakers, pirate metal fans, or guerrilla knitting-circle members, likeminded outsiders have infinite ways to connect these days through social media networks. But a massive show devoted to zine culture at Vancouver Art Gallery hearkens back to a time when community networks took a much more tangible form.

One of the most visceral physical representations of those networks in the exhibit, called Copy Machine Manifestos, is artist and filmmaker K8 Hardy’s Envelope Quilt. It’s a riotous, wall-filling stitched and glued tapestry of handwritten, illustrated, and stamped envelopes received through correspondences during the 1990s Riot Grrrl movement. It’s a crazy patchwork of doodle-covered missives from around the U.S. and the world, as fans connected over bands like Bikini Kill and Jack Off Jill, female power, and outrage over violence against women. The installation ties in nicely to the first room of the show, devoted to zines’ roots in the mail-art scene of the ’60s and ’70s (with its strong Vancouver connections).

Envelope Quilt perfectly captures a time when, with a pen, paper, staples, and photocopiers, you could raise your voice and bring together a network of strangers who thought the same way. As Vancouver Art Gallery deputy director and director of curatorial programs Eva Respini put it during a recent tour of the show, “Zines built and fomented community in a way that I feel is needed more than ever today.”

The ambitious exhibition—the first major museum show devoted to zines–was organized by the Brooklyn Museum, and curated by American art historians Branden W. Joseph and Drew Sawyer. Copy Machine Manifestos encompasses more than 1,000 works, augmenting artist zines with videos, sculptures, photographs, and other pieces. It’s expansive—but speaking to the reach of the artform, it barely scratches the surface of the zines circulating through the ’70s, ’80s, and ’90s.

Pointing out the main difference between the social media underground-culture networks of today and these miniature manifestos, Sawyer said: “Zines aren’t run by organizations that use algorithms or who can censor things. They can't be as easily surveilled or censored.” That’s why you saw them pop up again during Black Lives Matter and other protests of 2020, he added.

“Zines have a certain intimacy to them—a different kind of intimacy than online,” added Joseph. “There’s something about the physical interface—the connection that one feels with the maker of zines.”

The show is organized chronologically, with rooms devoted to such areas as “The Punk Explosion: 1975–1990” and “Queer & Feminist Undergrounds: 1987–2000”. Within those eras, you’ll see nods to skateboarding, fashion, and other communities—as niche as, say, Homeboy Beautiful’s queer Chicano readership. (West Coast omissions include heavyweights Maximum Rocknroll, Flipside, and Slash, and local legends like Idle Thoughts, Bazooka Comiks, and SnotRag—but an exhaustive collection would take up several buildings.)

Because the curators focused on original, rather than reproduced, zines, the majority of artifacts unfortunately sit behind glass, only their covers visible. You long to page through, say, the acerbic media critiques inside Kathleen Hanna’s My life with Evan Dando, Popstar (even if it was on an iPad by the installation). Albeit some of those covers are highly entertaining: Hippie Dick! from the ‘70s, or skateboarder-artist Ed Templeton’s equally self-explanatory Teenage Smokers from the 1990s. A big draw is the wall full of 1980s zines by underground renegade turned art star Raymond Pettibon, creator of Black Flag’s iconic four-bar logo and legendary record covers for the likes of Sonic Youth and Minutemen. With cryptic titles like Tripping Corpse and Poetic Use of Blood, they’re fascinating rough studies in his singular shadowy-noir style, expressive and sinister in black and white.

Raymond Pettibon’s zines, installation view detail. (Jane’s Book of Fighting, 1985; Poetic Use of Blood, “Double Crossed to Death”, 1989 (with Nelson Tarpenny); A Can at the Crossroads, 1985, collection Philip Aarons and Shelley Fox Aarons.

LTTR (Ginger Brooks Takahashi, K8 Hardy, Every Ocean Hughes and Ulrike Müller), LTTR, no. 2, Listen Translate Translate Record, August 2003, offset zine (with booklet, screenprinted band, altered tampon and compact disc), Collection Philip Aarons and Shelley Fox Aarons. Photo by David Vu

“Although zines were cheap and ephemeral when they were made, some of them are exceedingly rare,” explained Sawyer of having to put the zines behind glass. “Some of these are the only one we were able to find–some were in storage, others under people’s beds.” Over the course of his and Joseph’s five years of research, he added they spent a lot of time discussing what a zine was and how to showcase it in an institutional setting it was never originally intended for.

Among the discoveries here, music fans will want to spend some time studying homo-core punk icon and artist Vaginal Davis’s Rectus/Lingus, 1990 (History of Punk Timeline for J.D.s). A meticulously hand-scrawled diagram tracing the L.A. punk scene, it provided a blueprint for G.B. Jones and Bruce LaBruce’s influential zine J.D.s. There are shoutouts to Vancouver’s D.O.A. and Joe “Shithead” Keithley; extra doodled emphasis on Screamers, Weirdos, and Nerves; and tangents into The Gun Club, The Zeros, and Cambridge Apostles.

Vancouver standout Ho Tam has a high-profile presence here, his art zines The Yellow Pages and Idol + Worship using imagery and text to critique North American stereotypes of Asian cultures. They’re shown alongside his 1994 oil-on-masonite series Matinee Idols, deadpan pop-art-style portraits of Asian pop stars set over brand names. Also on view is Tam’s The Yellow Pages video, with its cutting juxtaposition of found images (Godzilla, tai chi practitioners, North American Asian sauce labels, Chinese Olympic gymnasts) and text (“Asian Crimes”, “Head Tax”, “M.S.G.”). His Hotam Press is helping to keep zine culture alive today.

In the show’s final chamber, devoted to 2010 to the present, you can check out such contemporary distribution systems as a custom-made cart that sold zines with snacks. There’s also evidence that the artform is still useful to rabble rousers, forming networks around Indigenous activism, immigrant rights, and other political issues. As you exit, hit a reading lounge to page through local zines by the likes of Cheryl Hamilton and Sonja Ahlers, making it clear the form is still thriving despite the omnipresence of screens and social media.

What comes through most in this sprawling show is the frantic flurry of images, opinions, and raucous, radical ideas—as Joseph called it, “the multitude of voices”.

He pointed out, as well, that Copy Machine Manifestos has become much more than a deep dive into zine culture.

“It’s also a show about art—an alternative history of the perception and development of pop art, of performance, of conceptual art,” he said, “and in doing that, you broaden those areas to a whole lot of individuals that don't get recognized.” ![]()