Xicanx people combine art and activism for social justice and change

Most of the artists in Xicanx: Dreamers + Changemakers /Soñadores + creadores del cambio at MOA are exhibiting in Canada for the first time

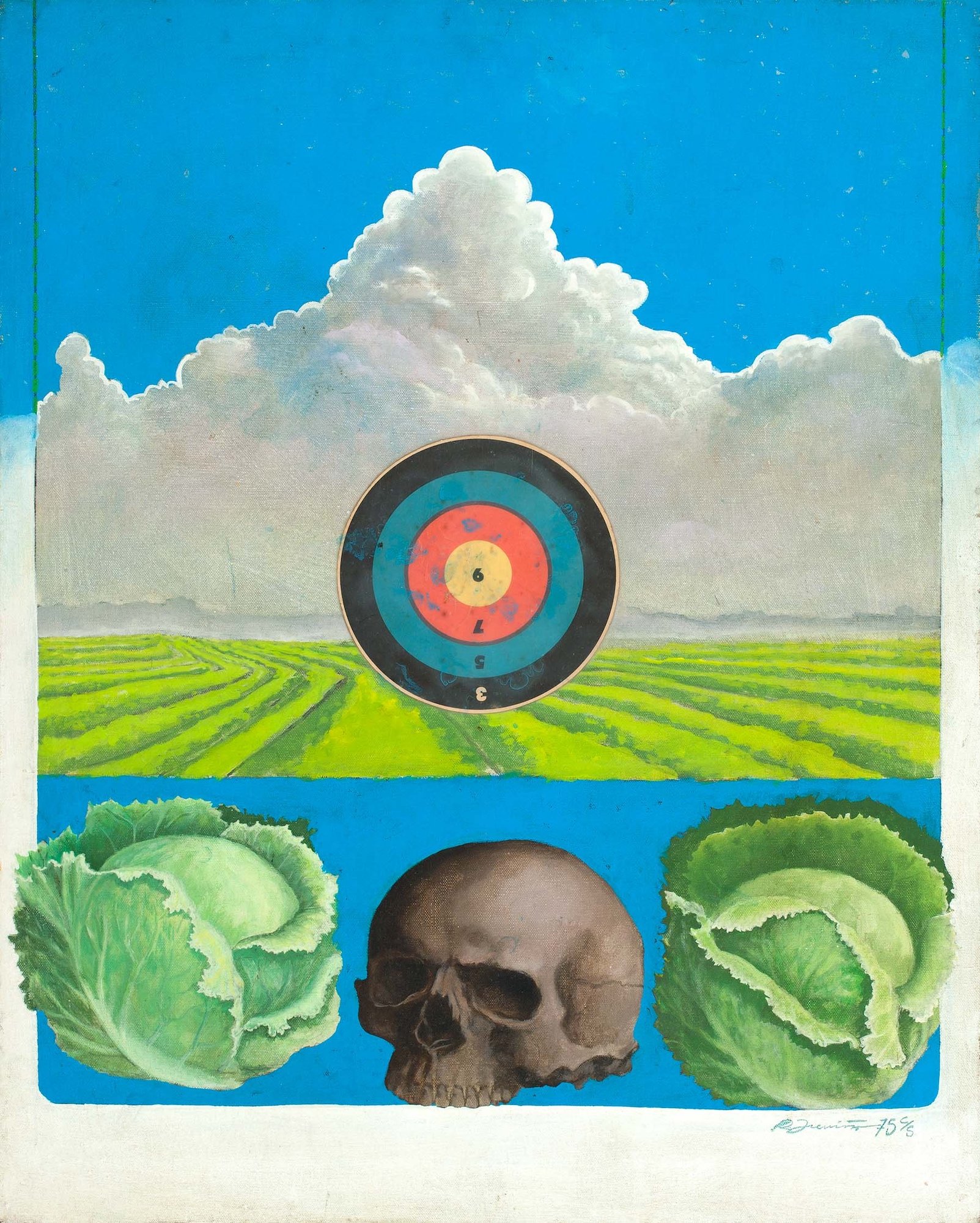

Lettuce Field with Target and Skull, Rudy Trevino. Collection of the artist. Photo courtesy of the artist

The Museum of Anthropology (MOA) at UBC and The Americas Research Network (ARENET) present Xicanx: Dreamers + Changemakers/Soñadores + creadores del cambio at MOA from May 12 to January 1, 2023.

THE 33 ARTISTS who make up Xicanx: Dreamers + Changemakers / Soñadores + creadores del cambio, which is having its world premiere in Vancouver, are Xicanx. Pronounced chi-can-x and the neutral grammatical gender of chicano/a, the term encompasses those who identify as Mexican American and who are of diverse backgrounds, including Mestizo/a (mixed ancestry with an Indigenous heritage), feminist, queer, non-binary, immigrant, and more. They combine visual art and activism, a tradition going back to the 1960s and ’70s, rooted in the U.S. civil-rights movement and El Movimiento, the Chicano civil-rights movement. Working in a range of mediums, Xicanx continue to fight for social justice through their art.

Xicanx artists address pressing issues such as voting rights, education, land rights, immigration, labour rights, and more in their work, says Greta de León, executive director of The Americas Research Network and co-curator of Xicanx: Dreamers + Changemakers/Soñadores + creadores del cambio with Jill Baird, MOA’s curator of education. Being Xicanx is about more than representing heritage and gender, de León explains; it also means accepting a responsibility to fight for their community, culture, and human rights. Being Xicanx, de León says, is to choose an identity.

“All of the artists in the show are U.S. citizens of Mexican origin,” de León tells Stir. “They self-identify as chicano/chicana/Xicanx, and this implies a call to action, a commitment to activism and a historical awareness.”

No Hate No Fear, Roberto Jose Gonzalez. Collection of the artist. Photo courtesy of the artist

The participating artists hail from Arizona, California, Colorado, New Mexico, New York, and Texas, most of them exhibiting in Canada for the first time. With works spanning from 1970 to 2022, the exhibition is centered around five themes: neighbourhoods, identity, borderlands, home, and activism. Each theme is accompanied by quotes from Xicanx writers, scholars, or artists, allowing the voices of the community to tell their own stories. The show sheds light on a critical social movement that has been largely neglected in history books.

“The Chicano movement is often overlooked as a key component of the civil rights movement in the U.S. and was and still is very important in promoting and pursuing equal rights, representation, identity, language, gender, labour, education, and so on,” de León says. “Also, their contribution to the cultural landscape in the U.S. and Mexico needs to be more acknowledged. Their music, cuisine, literature, and films are incredibly vast and diverse.

“I believe Chicanos have been misunderstood and alienated by both Mexican nationals and other U.S. citizens,” she says. “This tension is also a fertile ground. They have reclaimed derogatory terms and recontextualized them like Rasquachismo, Pocho, and Chola/o. I admire how incredibly resilient and creative they are.”

Rasquachismo comes from the word rasquache, which means “leftover” or “of little value” and has become associated with “lower class”. Coined by Chicano scholar Tomás Ybarra Frausto, Rasquachismo reflects an attitude and an artistic sensibility, particularly of the underdog. One of the works on display at Xicanx celebrates this perspective, a newly commissioned site-specific altar installation with a spoken-word video component by David Zamora Casas. The San Antonio-based artist and curator has created politically motivated performances under the name Nuclear Meltdown since 1985 and describes his work as a “conscious radical act to create and move forward dialogue which strives for an inclusive and eco-friendly, empathetic world”.

Citlali: Cuando Eramos Sanos, Debora Kuetzpal Vazquez. Collection of the artist. Photo courtesy of the artist

Other pieces include Rudy Treviño’s Lettuce Field with Target and Skull (1975), a painting that confronts the labour unrest and immigration issues at the heart of protests in the 1970s primarily by Mexican and Mexican-American farmworkers; photographs of artist and muralist Judith F. Baca’s 1976 performance installation Judith F. Baca as La Pachuca, in which she plays with an unapologetically bold Chicana identity in an artistic movement often dominated by the male lens; and Alejandro Diaz’s Make Tacos Not War (2017), a simple, powerful call for peace and good food.

Roberto Jose Gonzalez’s diptych El Paso 8/3/19 and No Hate, No Fear (2019) honours the 23 victims of the August 3, 2019 El Paso Walmart shooting, the deadliest attack on Latinos in modern American history. The artist represents the massacre through skeletons, evoking Mexican traditions of Día de los Muertos.

Tres Marias (detail), Judith F. Baca. Collection of the artist. Photo courtesy of the artist

Queer and non-binary artists are essential to the Xicanx community. On display in Xicanx is queer feminist Debora Kuetzpal Vasquez’s 2012 Citali: Cuando Eramos Sanos, a cartoon anti-hero who challenges social and political issues pertaining to womxn and La Raza (culturally translated as “the people”). Non-binary artist Moises Salazar uses materials and techniques commonly described as women’s work, such as crocheting, glitter, and textiles, to convey their struggle for acceptance.

Many of the themes in the exhibition reflect some of the same issues related to Indigenous rights and social justice happening here at home and around the world.

“I think in general, globally, we are seeing a rise in intolerance and discrimination,” de León says. “It is more visible because we are more connected now and because populist rhetoric is validating hate speech with very little accountability.

“It is a privilege to present the evolution of a political-social-art movement,” she adds. “The Xicanx artists are quite different now than in the ’70s—more women, more queer artists. However, the fight for equality, rights, and recognition is still very current.”