Outrage meets experimentation in yellow objects' multimedia battle cry for Hong Kong

Shadow puppets, sticky notes, projections, and umbrellas: rice and beans theatre work that confounds, rallies, and pushes form

The Firehall Arts Centre presents rice and beans theatre’s yellow objects until May 22, with showtimes on the hour from 6 to 9 pm on weeknights, and from 3 to 5 pm and 7 to 9 pm on weekends.

IT’S ALMOST impossible to categorize the experience of the new “exhibition” yellow objects, which mixes theatre, protest act, visual art and audio installation, puppetry, and projections to get across its message.

Highly experimental and deeply emotionally charged, the rice and beans theatre presentation is a defiant, walk-through monument to the oppression happening in Hong Kong, birthplace of its writer-creator Derek Chan.

The installation is driven by anger and outrage at the closing fist of Chinese rule on the Asian territory. Start with the broken promises of “one country, two systems”, and then look to the more recent violence, imprisonment, and disappearance of unknowable numbers that have happened in the wake of 2019-20 street protests. Most striking is that this kind of blatant criticism of the Chinese rule could never take place without severe repercussions in Hong Kong—a fact eerily underscored by the fact that many of the participating artists in this production are credited anonymously, even here in Canada.

Walking into the darkened main room at the Firehall, we are surrounded by toppled piles of school chairs (a sight that instantly recalls the siege and protest at Hong Kong’s higher learning institutions early last year). It is 2050, and an old radio in a spotlight broadcasts Big Brother-like warnings that citizens should respect the law or face imprisonment and that they should report fugitives.

The journey follows the story of a young Vancouverite, Sandra Wong, who returns to Hong Kong with her grandmother’s ashes, meeting an old janitor, Uncle Chan, to help her uncover what happened to the city 30 years in the past. In a clever work-around for a pandemic era that prevents actors from performing live on stage, the characters talk over speakers and never appear; instead, Sandra takes the form of empty shoes and a roller suitcase; we hear the janitor speak as a spotlight illuminates his mop bucket. It’s surprisingly effective as you stand socially distanced in the dark.

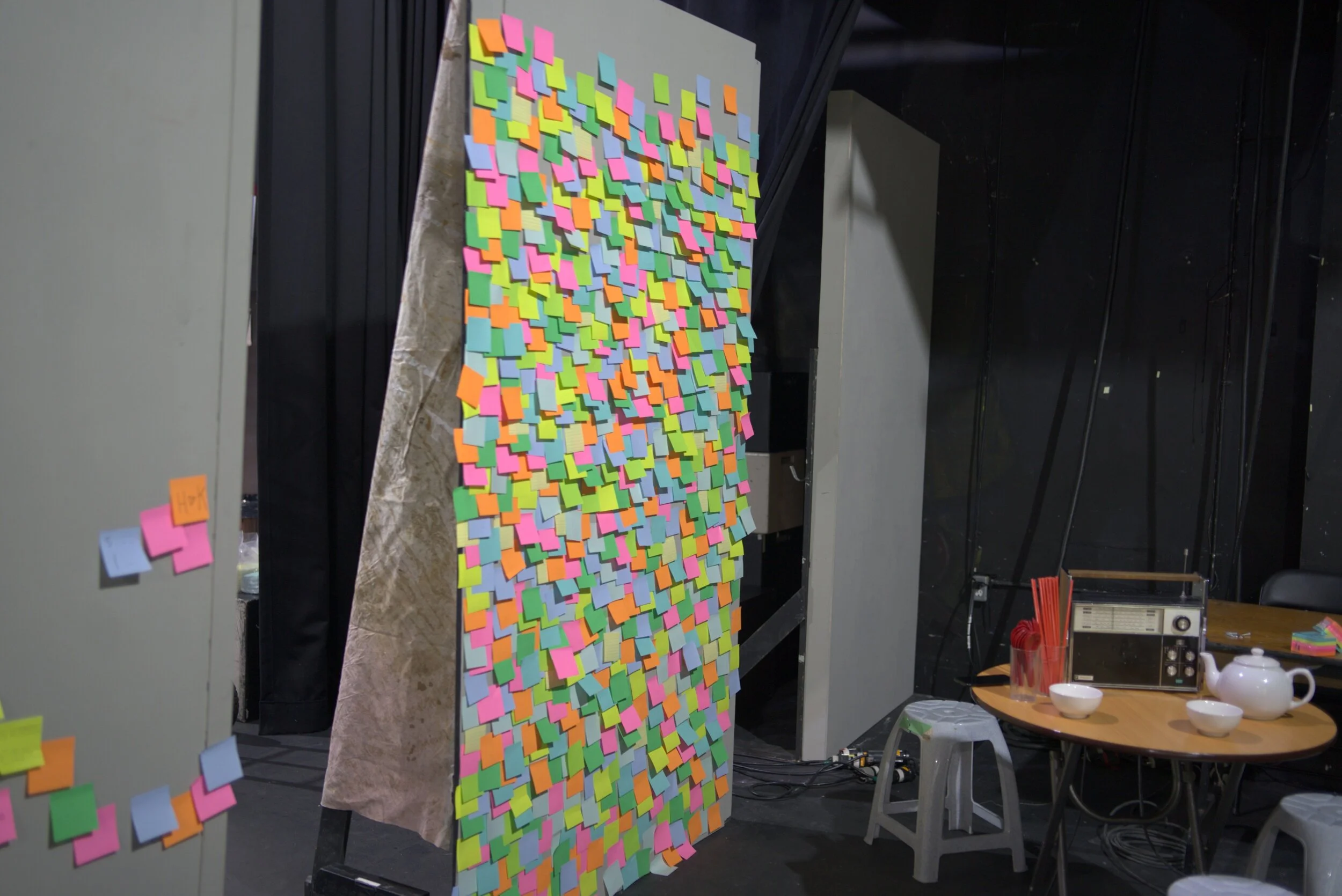

But their journey fragments and dissolves, becoming more and more cryptic as we enter a second room—one that brings to life the resistance movement. Covering one wall, neon sticky notes are emblazoned with protest slogans—a nod to the colourful Post-It memorials that have become a symbol of the movement in Hong Kong. Elsewhere, the ghosts of the past are literally conjured, shaking tables and appearing through projections and puppetry. Meanwhile, a video screen counts out the activists’ key five demands and offers school-like “lessons” on the more loaded terminology of the conflict—the fact that police call protestors “cockroaches”, and the origins of the term “yellow objects”. In one of the show’s darkest moments, an unseen citizen undergoes a brutal interrogation by a policeman.

The installation is infused with Eastern art forms, from the sound of the wood-block bangzi, to the use of the traditional shadow puppets (with controversial Hong Kong chief executive Carrie Lam as the villain—and true “puppet”).

The final portion of the exhibit takes place in the Firehall courtyard. Suffice it to say, it takes the form of a graveyard of umbrellas—the symbol of the movement—as seen from a doomed future.

At times the story itself is confusing and hard to follow, especially when our invisible protagonists are lost in the sound and fury. (Make sure to visit the project's online component here to fill in some of the narrative details.) Ultimately, yellow objects works best on the level of a visual and aural artistic explosion. Let’s face it: outrage by definition is hard to contain, and it doesn’t call for a subdued tone. What we do get is an ambitious and sometimes chaotic exposé of the crisis in Hong Kong, expressed in ways that headlines and nightly news clips on TV just can't. It's revolutionary in form and content; a rallying cry for dissidents. Visit it for its sheer, messy audacity—an audacity that only democracy and free speech can allow.