Major Jean Paul Riopelle exhibition comes to Whistler’s Audain Art Museum

The show focuses on a lesser-known period of the iconic artist’s life—and raises questions about the collection of Indigenous art

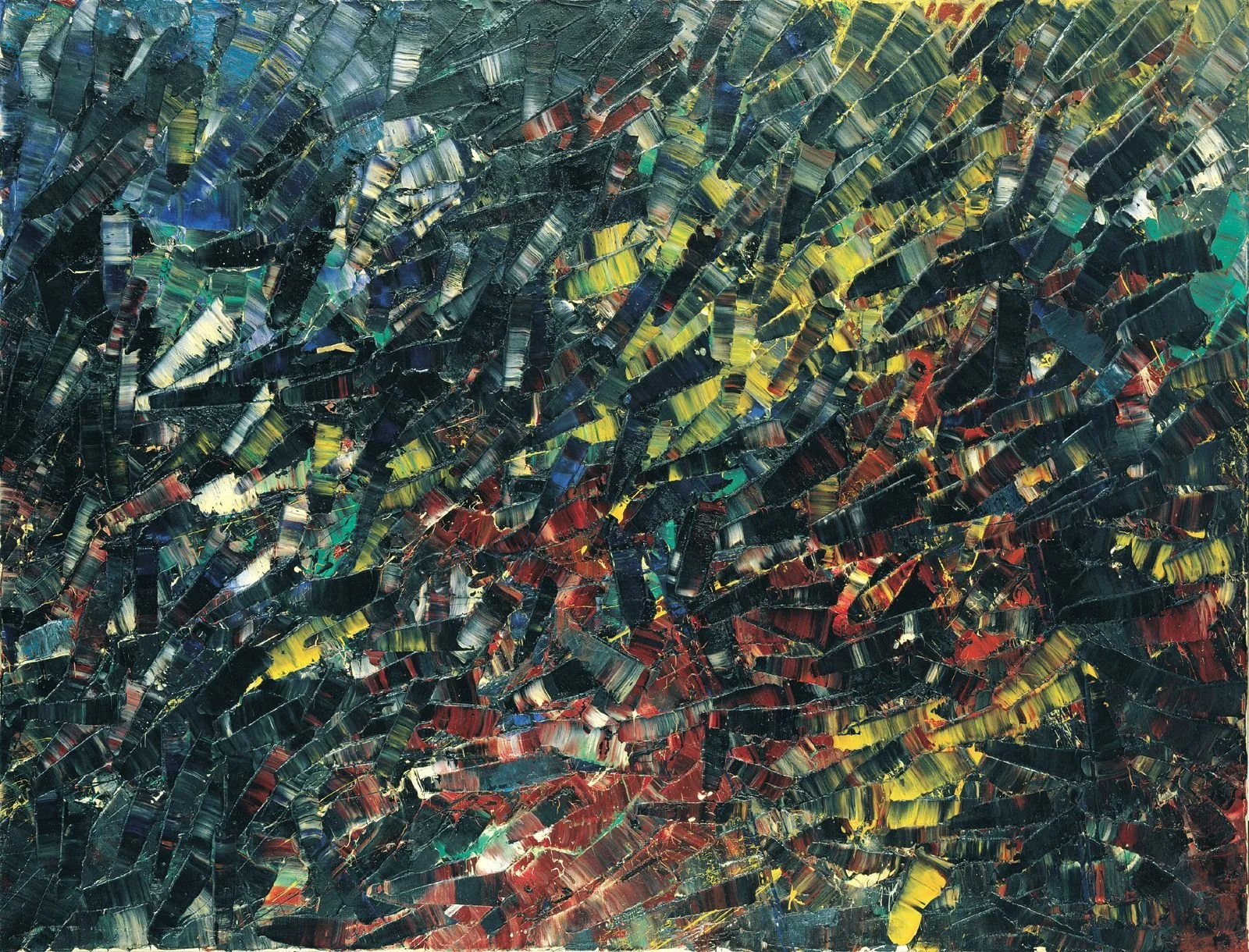

Jean Paul Riopelle (1923-2002), Blizzard, 1954, oil on canvas, 95.5 x125 cm. Private collection. ©Estate of Jean Paul Riopelle /SOCAN (2021).

Audain Art Museum presents Riopelle: The Call of Northern Landscapes and Indigenous Cultures, developed by the Montreal Museum of Fine Arts, from October 23 to February 21, 2022.

RIOPELLE: THE CALL of Northern Landscapes and Indigenous Cultures marks a point of pride for Whistler’s Audain Art Museum. It is the first gallery in the world to host the ambitious travelling exhibition of Jean Paul Riopelle, one of 20th-century Canada’s most prolific and important artists, outside of its birthplace at the Montreal Museum of Fine Arts. The far-reaching show features nearly 160 pieces and more than 150 artifacts and archival documents that shed new light on the internationally renowned Quebec painter’s work from the 1950s onward, with a particular focus on the 1970s, a lesser-known period of his life.

In revealing Riopelle’s fascination with Indigenous communities and artworks, the exhibition may also be the Whistler venue’s most challenging show to date. Audain Art Museum director and chief curator Curtis Collins is fully expecting and encouraging dialogue, debate, difficult discussions, and disagreement.

“The show is important as a new look at Riopelle’s work, and that is also coupled with the potential for a museum critique when it comes to historic First Nations work,” Collins says. “Those are the two edges of the show.”

First, a bit of background: born in Montreal in 1923, Riopelle studied at the École du Meuble de Montréal. There, he met painter Paul-Émile Borduas and the Automatistes. He was one of 16 artists who signed the 1948 Refus global (Total Refusal), an anti-establishment and anti-religious manifesto. Over the ensuing two decades, he lived and worked in France. He fell in with the Surrealists, meeting people like André Breton and Georges Duthuit, who were collectors of Indigenous North American art, including Inuit and First Nations masks. In the 1970s, back in Canada, Riopelle was drawn to the North, going on numerous hunting and fishing trips to places such as Nunavik and Nunavut with his friend Champlain Charest, a Quebec restaurateur and wine collector who owned a seaplane.

Riopelle passed away in Isle-aux-Grues, Quebec, in 2002, and today his work can be found in public collections around the world, including the Guggenheim Museum in New York, Centre Pompidou in Paris, and Hirshhorn Museum in Washington, DC. In 2019, the Jean Paul Riopelle Foundation was launched to preserve, promote, and disseminate his work and celebrate his legacy. (Michael Audain, who co-founded the Audain Art Museum with his wife, Yoshiko Karasawa, is the foundation’s visionary and one of its six founding members. The organization is the realization of Riopelle’s dream of communicating his world views and his passion for art; he also wanted to inspire the next generation of visual artists by giving them a space to explore, experiment, and collaborate.)

Based on original research with the goal of immersing viewers in Riopelle’s approach to artistic production and the inspiration behind his work, Riopelle: The Call of Northern Landscapes and Indigenous Cultures was organized by MMFA guest curators Andréanne Roy and Yseult Riopelle (the artist’s daughter) as well as MMFA’s Jacques Des Rochers, curator of Quebec and Canadian art (before 1945).

The exhibition takes a chronological and thematic approach to Riopelle’s artistic output, with a broad cross-section of distinct work. In addition to paintings, sculptures, and works on paper, the show features two recently restored major works: the monumental sculpture La Fontaine (circa 1964-1977) as well as Point de rencontre (1963), the artist’s sole commissioned work, a canvas previously exhibited at the Opéra Bastille in Paris. There are letters, magazines, photographs, and videos to give a sense of where his inspiration came from as well as historical works from the Yup’ik, Kwakwaka’wakw, and Tlingit communities. In honouring Riopelle’s fascination with living cultures, there are pieces by contemporary Indigenous artists, such as Luke Akuptangoak, Noah Arpatuq Echalook, Mattiusi Iyaituk, Pudlo Pudlat, and Beau Dick. The show also incorporates a commissioned work by Tlingit artist Alison Bremner as well as a new MMFA acquisition by Cree artist Duane Linklater.

It is, in a word, complex.

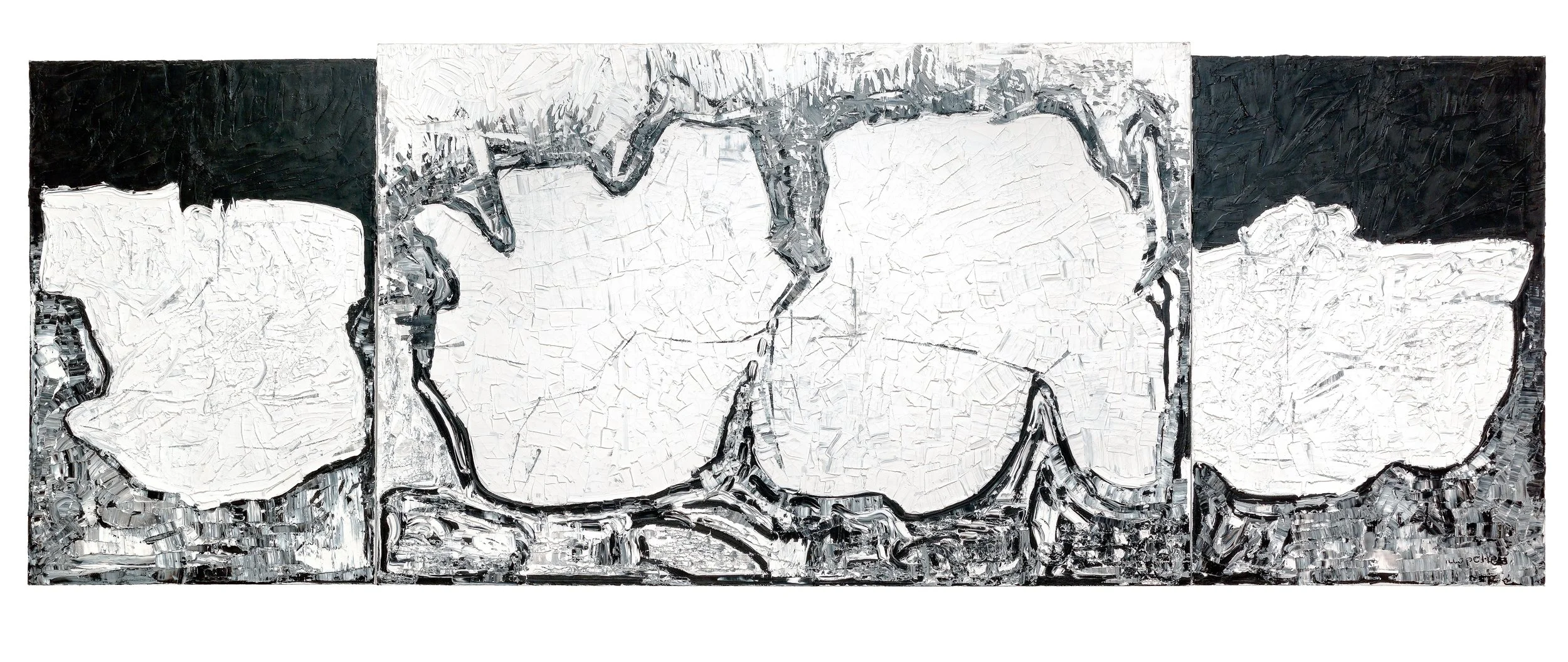

Jean Paul Riopelle (1923-2002), L’esprit de la ficelle (triptych), 1971, acrylic on lithograph mounted on canvas, 160 x 360 cm. Private collection. ©Estate of Jean Paul Riopelle / SOCAN (2021). Photoarchives catalogue raisonné Jean Paul Riopelle.

Noah Arpatuq Echalook (born in 1946), Woman Playing a String Game,1987, dark green stone, ivory, hide, 26 x 39 x 24 cm. National Gallery of Canada, Ottawa, purchased in 1991. ©Fédération descoopératives du Nouveau-Québec. Photo NGC.

Collins explains that MMAF first approached him approximately two and a half years ago about the possibility of holding the exhibition in Whistler. He was especially intrigued by the show’s focus on the iconic artist’s work from the 1970s, which presents variations from what many would expect or understand of Riopelle.

“His work becomes much more figurative in the sense that he’s rendering somewhat identifiable objects and landscapes,” Collins says on the line from Audain Art Museum, which is situated on unceded territory of the Squamish Nation and Lil’wat Nation. The image of an owl, for instance, plays an important role in the show, both as a painting (Grand duc, 1970) and as a bronze (Femme hibou,1969–70, cast initiated about 1971). There are paintings that explore the influence of Riopelle’s hunting and fishing trips, as in Icebergs (1977). The Jeux de ficelles series, inspired by Canadian anthropologist Guy Mary-Rousselière’s 1969 book Les jeux de ficelle des Arviligjuarmiut, may have also been based on discoveries he made on those Northern expeditions, namely Inuit games called ajaraaq. The games, which consist of knotting a string around the fingers to create various figures called ayarauseq, also have a ritual function. “The strings rendered by Riopelle are sometimes inspired directly by the ajaraaq figures; at other times, the artist takes great liberties in creating his own motifs,” the MMAF notes in a release.

Soleil de minuit (Quatuor en blanc), from 1977, is a quadriptych that depicts the midnight sun entirely in black and white. “Most people associate Riopelle’s work with these highly coloured screens; in this case, for example, there’s a series of four sequential paintings of the midnight sun all in black and white,” Collins says. “It’s an interesting approach to a subject matter you would normally associate with colour.”

Basil Zarov (1905 (?)-1998), Jean Paul Riopelle outside of the Studio at Sainte-Marguerite-du-Lac-Masson with “La Défaite” in the Distance,about 1976, black and white photograph. Library and Archives Canada, Ottawa. ©Estate of Jean Paul Riopelle / SOCAN (2021). Photo©Library and Archives Canada. Reproduced with the permission of Library and Archives Canada/Basil Zarov fonds/e011205146.

In addition to books and publications that Riopelle was looking at during his time in France, the show also includes pieces such as masks from various Indigenous communities that he came across while living there—leading to what Collins describes as a problematic context of the show within the Audain Art Museum and B.C. in general.

“You have historic material--Northwest Coast masks for the most part--in the context of trying to expand on an understanding Riopelle’s work,” Collins says. “Issues around appropriation are important to understand but also the provenance of how such materials come into collectors’ hands. That is an open discussion that we want to have with our visitors, but it’s also an open discussion we’re already having with our visitors in relation to our permanent collection in the sense that our permanent collection also features historic Northwest Coast masks and that’s a very strong feature. Both historic and contemporary Northwest Coast Indigenous art is central to our permanent collection, so in some ways this show makes a lot of sense in this building and the fact that we can bounce it back and forth off the collection.

“It is problematic in terms of how some of these older objects would have come into collections,” he adds. “We have to open that up—that these works are out of context, they’ve been removed from their ceremonial function, and they’re no longer in the hands of the makers or the ancestors of those makers.”

From 1977 to 1979, Riopelle produced three groups of works featuring iconography he borrowed directly from the First Nations of the Northwest Coast and the Inuit. One was a series of silverpoint drawings whose main subjects were Northwest Coast masks and objects. He reproduced images from Claude Lévi-Strauss’s 1975 La voie des masques. And The Lied à Émile Nelligan lithographic suite featured Indigenous iconography, including masks from Robert Bruce Inverarity’s 1955 book Art of the Northwest Coast Indians.

“Impressed with a profound admiration for Indigenous peoples and their material cultures, Riopelle realized the dialogic possibilities of appropriation and paid them homage in such a way that today leaves him open to reproach,” MMFA states in a release. “But he was a man of his time, and Euro- Canadians of his time were not yet engaging in the necessary postcolonial interrogations of today.”

Jean Paul Riopelle (1923-2002), Pangnirtung (triptych), 1977, oil on canvas, 200 x 560 cm. Musée national des beaux-arts du Québec, achat grâce à une contribution spéciale de la Société des loteries du Québec. Inv. 1997.113. ©Estate of Jean Paul Riopelle / SOCAN (2021). Photo MNBAQ, Idra Labrie.

In the lead-up to the exhibition, Collins consulted with Xwalactun, an internationally recognized artist in wood, paper, stone, glass, rock, and metals of Squamish and Kwakwakw'wakw heritage. Having studied at Emily Carr University, Xwalactun (whose English name is Rick Harry) is a member of the Order of B.C. and sits on Audain Art Museum’s board of trustees. His He-yay meymuy (Big Flood, 2014-15), an aluminum totem with LED lights, welcomes visitors at the museum’s entrance.

“Xwalactun, as a member of the Squamish Nation, because of his position on the board, and because of his long-standing reputation as a well-respected artist across Canada and internationally, is someone that I look to for guidance on a regular basis, and he’s been very generous with his time and with his advice,” Collins says. “It was important for him that we open up the discussion and that the museum is open to being critiqued.”

Xwalactun focuses on themes of unity, spirituality, and growth in his work. Although he was not familiar with Riopelle prior to his meeting with Collins, he sees the exhibition as a way to bring about crucial conversation and understanding.

“I’m just learning about him,” Xwalactun says of Riopelle in a phone interview with Stir. “When I saw some of the images, I saw some that he took from an actual original artist’s work and made it his own in a sketch. If I were to copy another artist’s work, it isn’t right. I want to understand why he copied it, and I have a lot to learn about that. Going through this show, I might learn something new about why he did that.

“Other artists or curators going through it might have some reservations about it,” he says. “I’m for sure open to learning and to going through the show just to hear people’s thoughts, to listen to all the dialogue in all different directions to see where it will take us. It’s one step of a conversation about reconciliation and where we are at today with it and where can we go tomorrow. As artists, we have our own backgrounds and we’re learning as we go; I’m interested to learn more.”

The museum’s temporary wing has been completely transformed for the exhibition, with custom-made glass showcases to protect historic material; the walls are painted a dark green. A companion publication features 11 essays by authors and artists, including Guy Sioui Durand, a sociologist, historian, playwright, director, actor, and filmmaker of the Wendake Huron-Wendat Nation.

“For him to contribute to this book told me that there’s an area of discussion that I’m comfortable with in the sense that we may take some critique from Indigenous curators, academics, artists…” Collins says. “However, I would say that the show has been vetted to that extent, and no one can assume that Indigenous people across Canada or North America for that matter speak with a monolithic voice. There will be differences here, and again, there will be an area of discourse and critique. We’re going to get disagreement here.

“It’s a conversation that needs to happen here,” he adds. “It’s a conversation that’s related to our collection here but it’s also a conversation that extends beyond B.C. “

For more information, see Audain Art Museum.