In Tranquility of Communion, Rotimi Fani-Kayode's images of queer desire take on new urgency

Showing at the Polygon Gallery, British photo-artist broke Thatcher-era taboos with luminous photographs that defy easy categorization

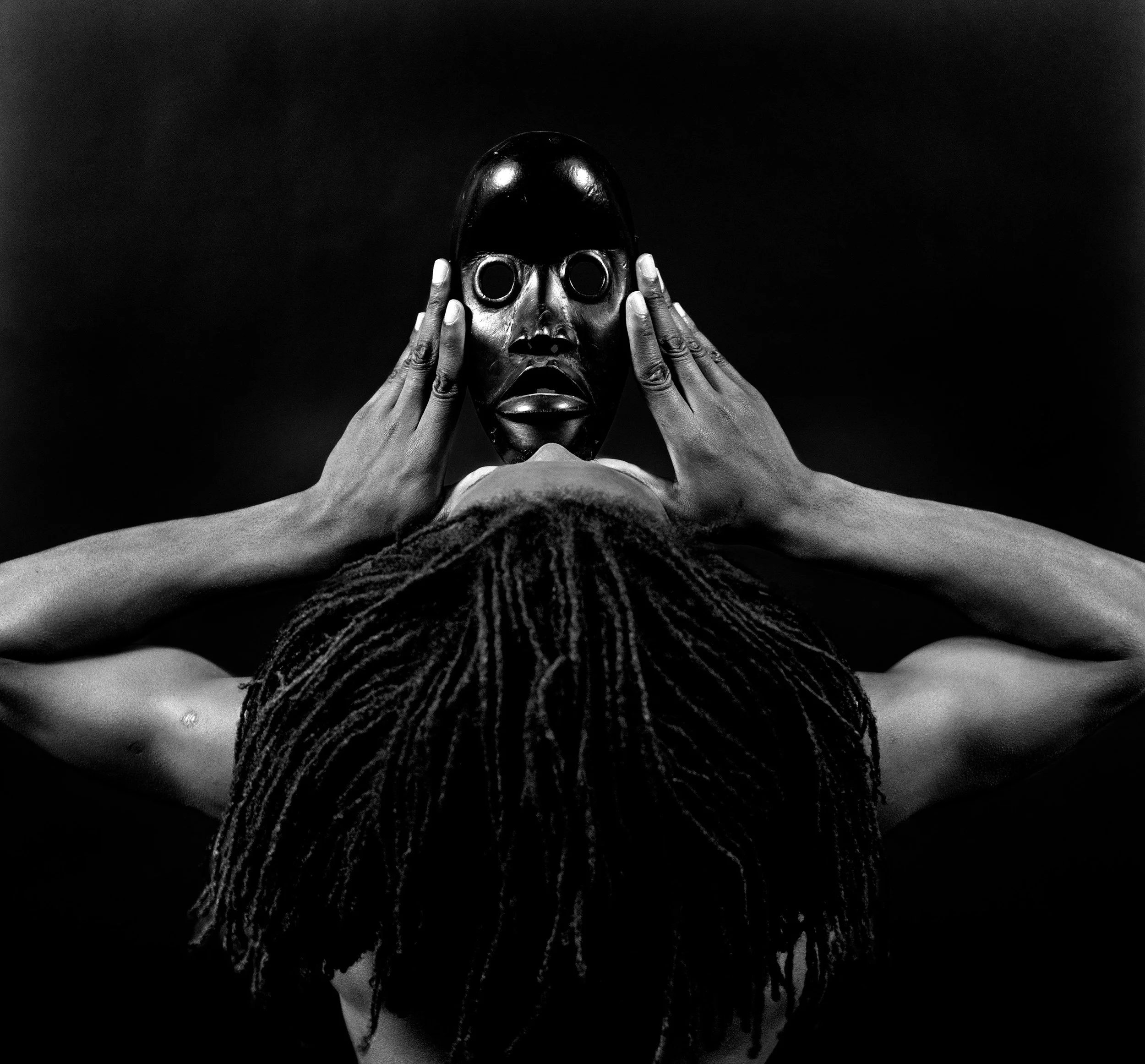

Rotimi Fani-Kayode, Dan Mask, 1989. Courtesy of Autograph, London

Rotimi Fani-Kayode: Tranquility of Communion is at The Polygon Gallery to May 25

IN THE MID-1980s, Margaret Thatcher ruled England with as much zeal for free-market fundamentalism as for traditional family and societal roles. The era was marked by a push for assimilation and race riots.

It was, in short, not a great time to be an outsider.

Into this era came Black, queer photo artist Rotimi Fani-Kayode, who created images that defied easy categorization, interweaving the expression of queer desire with Yoruba cosmologies and pure, soulful celebration of the Black body in all its complexity. Across hundreds of images at the major new Polygon Gallery exhibit Rotimi Fani-Kayode: Tranquility of Communion, ceremonial leaves, Nigerian masks, and, sometimes, bondage straps intermingle in his portraits, the Black skin of his subjects lit like it glows from within.

The Brixton-based talent’s tragically brief career lasted only six years before he died from AIDS complications in 1989, at just 34 years old.

As the prolific Fani-Kayode himself put it in his essay “Traces of Ecstasy”: “On three counts I am an outsider: in matters of sexuality, in terms of geographical and cultural dislocation; and in the sense of not having become the sort of respectably married professional my parents might have hoped for.”

“It was homophobic in nature, super conservative, aggressive, with hostile policing, and cultural institutions were very, very straight,” says Tranquility of Communion curator Mark Sealy in a phone interview with Stir from the British capital. The director of London’s Autograph gallery and photography professor at University of the Arts London is reflecting on the Thatcher era that he also experienced. “Class divide was massive, racial divide was huge. Gender inequality was diabolical. And racism—institutional racism—was completely rife.”

Yet the more than 200 images on display here—from intimately scaled early black-and-white shots to large, colour-saturated photographs—transcend that ugliness.

In Fani-Kayode’s powerful 1987 self-portrait Umbrella, the artist sits naked, legs crossed, holding up a white umbrella that obscures his face—but you can still see his head is upturned, ever looking for some higher plane. The umbrella, an iconic British object, serves as his protection but also obscures his face—possibly a reference to his invisibility as a person of colour in the queer community.

Sexuality meets ancestry in the same year’s Bronze Head, as a nude male’s buttocks lower provocatively onto the bust of a Yoruba god. The artist is merging the sensual and spiritual—in black-and-white, both forms have the same rich hue—giving reverence to then-taboo physical desires. A similar feel of oneness with the spiritual world comes across in the show’s most striking black-and-white image, Dan Mask: here, the artist holds an African mask reverentially above his own obscured face, his long locks flowing below it like a beard, his bent arms suggesting the mask’s “body” and giving it life.

The images feel prescient, celebrating difference when right-wing conservatism is rising again, trying to force people into boxes.

“Rotimi was trying to work something out, really,” Sealy observes. “And I think sometimes, if you’re just a bit ahead of the curve, it takes time for people to kind of catch up.

“Maybe some of these ideas, maybe they just don’t resolve,” he adds. “I’d like to think that these are kind of like signposts to future thinking, really. And I think some people have kind of caught up and taken the direction that they offer.”

Rotimi Fani-Kayode’s Umbrella, 1987. Courtesy of Autograph, London

Fani-Kayode was born in Lagos and moved to England after the outbreak of civil war in Nigeria. He later studied in the U.S., at Brooklyn’s Pratt Institute, before settling permanently in London, where he lived and worked until his untimely death in 1989.

During the 1980s, the studio was Fani-Kayode’s playground, where he could tap fantasy and myth and bring it to life.

“With these later colour, Caravaggio-esque, beautiful pieces, you can be in the dream,” Sealy observes. “They’re very theatre-orientated works—I think using the camera as a performative tool is really an essential way of reading his work. And that means that it’s a dialogue with theatre. It’s a dialogue with the classical traditions. There’s a sense of the sensual that is really important in reading the work. And I think we need to start drawing the difference between the erotic and the sensual.”

Amid the show’s exquisitely staged, vibrantly coloured later images, Adebiyi depicts a male who wears a crown of leaves and flowers, dressed up like the Roman god Bacchus of Caravaggio’s famous painting—but he’s holding an African mask instead of grapes.

As Polygon curator Elliott Ramsey pointed out at the exhibition’s opening night, Fani-Kayode’s complex, multilayered work often satirizes the primitivist or exoticized gestures of Black masculinity in Western art history.

Installation view of Rotimi Fani-Kayode: Tranquility of Communion, curated by Mark Sealy, at The Polygon Gallery. Photo by Dennis Ha

“It’s not to do with ‘Document my community and show you it,’” Sealy explains. “It's not a reportage. It’s a story of trying to actually build and articulate this idea of ecstasy and fantasy and desire and queerness. And it’s kind of infinite possibilities, if you like. And then tying up uniquely, I think, at the time, into an African-Yoruba cosmology is really quite special. I mean, it’s intellectually above and beyond just talking about the erotic.”

It has taken decades to gather Fani-Kayode’s photographs into Tranquility of Communion. The exhibition has travelled here from Autograph, the London gallery devoted to race, representation, and social justice.

“I feel as though since 1991 we’ve been trying to find the time to make this happen,” Sealy says. “He’s tied to the story of Autograph implicitly, because he was an early chair of the organization. And his story becomes increasingly significant as we care for the work.”

The delay in giving the artist his due speaks volumes. “It’s been difficult, it seems, in some places and spaces, to embrace his importance,” Sealy allows.

What is clear from the Polygon show is that the artist produced a massive volume of compelling work. At the same time, he expressed a vastness of thought on identity, queerness, desire, and dislocation in the little time he had.

There was an urgency to making art in Thatcher’s '80s, Sealy reflects. “I remember that, having been an art student in the '80s myself, there was a sense that things were pressing,” he says. “The time was short, and whatever opportunity you had to make something, you needed to grab it.” ![]()

Rotimi Fani-Kayode, Adebiyi, 1989. Courtesy of Autograph, London

![Theatre review: Complete Works of William Shakespeare (abridged) [revised] [again] takes pleasingly panicked tour of the Bard’s canon](https://images.squarespace-cdn.com/content/v1/5f10a7f0e4041a480cbbf0be/1752776963817-BS2BYYQMLMSGU9OG3E37/Nathan-Kay-and-Craig-Erickson.-Photo-By-Tim-Matheson.jpg)