Sidi Larbi Cherkaoui and Damien Jalet’s epic Babel 7.16 is a vivid reflection on a divided world

Streamed here as part of DanceHouse’s Digidance series, the Belgian work brings together 22 far-flung performers on a stage with ever-shifting metal frames

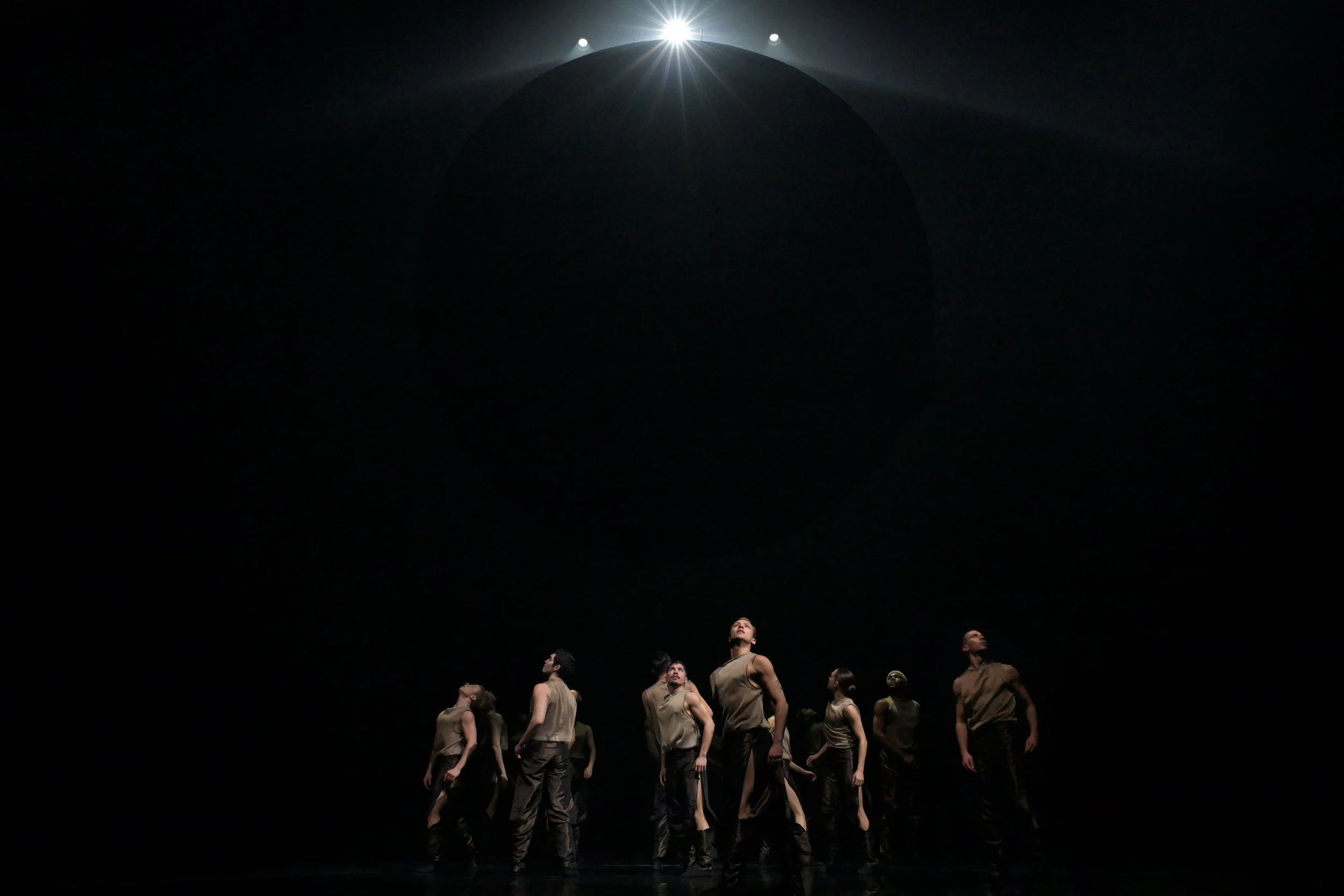

Babel 7.16 was staged in Avignon’s historic Palais de Papes. Photo by Christophe Raynaud de Lage

DanceHouse streams Babel 7.16 via Digidance from December 8 to 19

A DECADE AGO, DanceHouse considered bringing Sidi Larbi Cherkaoui and Damien Jalet’s Babel(words)—a 2010 production whose Belgian premiere had scored a coveted Olivier Award—to Vancouver.

At the time, the work that sent a dozen dancers of different nationalities moving through artist Antony Gormley’s huge metal-frame structure was just too big to bring to the Vancouver Playhouse stage.

Then, Cherkaoui’s Eastman dance company conjured an even larger-scale version of the show. Called Babel 7.16, it debuted at the 70th edition of the Festival d’Avignon in 2016, staged in the southern French city’s historic Cour d’Honneur of the Palais des Papes. And DanceHouse is finally able to bring it here—virtually, through its online Digidance program.

“Now, this larger version blows the notion of ‘epic’ off on an even greater scale and scope, but also in terms of duration,” says Dancehouse artistic and executive director Jim Smith. “They dig a lot deeper and explore ideas to a greater extent than the original version.”

The multilingual cast has been expanded to 22 performers hailing from 15 countries. Each brings not just their own distinct tongue—and there is a lot of multilingual “babble” in Babel.716—but the culture and training that live in their body. Classical ballet dancers perform alongside B-boys. In other words, they speak vastly different languages of dance, as well.

The rhythms that drive them are just as diverse: think taiko drums, bamboo flute, kokyu violin, and Renaissance songs. (Listen to the striking mashup in the trailer below.)

Like the original, Babel.716 riffs on the Biblical Tower of Babel story, in which humankind builds a tower skyward to draw closer to God. But He punishes them by dividing them into different nationalities and languages—making it forever impossible for them to work together again.

British sculptor Gormley’s metal frames shift and reshift into countless geometric forms that by turns connect, separate, and isolate the dancers. The dancers build, tear down, and rebuild the structure to resemble everything from cities to shelters.

Babel 7.16 features dancers inhabiting an ever-shifting landscape of metal frames. Photo by Christophe Raynaud de Lage

Eleven years since the show’s first incarnation, the work’s striking imagery, movement, and ideas have taken on more resonance than ever. This is an era when everything from a deadly virus to racial violence, a refugee crisis, and floodwaters are driving humankind apart.

“Think about the global crises we’re all contending with, be it the pandemic or the state of the environment,” observes Smith. “These global issues have created a need for us all to come together, and while there's a desire to do that, we still have this vulnerability of language in terms of really understanding what we communicate with one another.”

Smith points out that the seed for the project started in part in the language differences between Cherkaoui and Jalet themselves: in bilingual Belgium, one speaks Flemish and the other speaks French.

Separately, they’ve become two of the world’s hottest names in contemporary dance, defying categorization with every new project.

“They are of a generation that is, in many ways, challenging and smashing the idea of what a dance piece is,” Smith observes. “Both are challenging: What is dance? And what is movement?”

Flemish-Moroccan choreographer Cherkaoui has created work for companies like the Royal Ballet Flanders, where he’s artistic director, London’s Royal Ballet, and the Paris Opera Ballet. But he’s just as likely to choreograph a music video for Beyoncé and Jay-Z, or turn a manga series into a kinetic play (Pluto, 2015). Jalet works in dance across visual art, music, film, theatre, and fashion; projects include his critically acclaimed film The Ferryman, at the Venice Biennale, created with performance artist Marina Abramović and composer Ryuichi Sakamoto; and choreography for Antwerp Opera, Nederlands Dans Theater, and Madonna herself.

They’re a busy pair, in demand around the globe. And so the Digidance screening is a rare opportunity to see their ambitious collaboration here.

Their Babel 7.16 may be a story about division, but Digidance is very much about newfound connection. Pandemic innovation has made it possible to bring dance audiences together across Canada. Launched last year in response to COVID-19, Digidance is offered by Canada's leading dance presenters: DanceHouse, along with Toronto’s Harbourfront Centre, Ottawa’s National Arts Centre, and Montreal’s Danse Danse, in association with Calgary’s Springboard Performance. Even though live performances have returned to Vancouver, the platform has now evolved as an outlet for spectacles that are just too big to travel here—including Brazil’s equally large-scale Dog Without Feathers, by Deborah Colker, which screened earlier this season.

“Even though Digidance was a response to a crisis—to a situation that wouldn't allow us to do what we usually do and that was part of that terrible thing of pivoting—what a huge opportunity it has turned out to be,” remarks Smith. “It has opened up this possibility to bring to the communities and audiences that we’re trying to feed with an international perspective on the dance world a whole new level of work that is really, really large and that we would never be able to bring to our theatres or our audiences.”