In Bulleh Shah: Seeker of Light, Gaurav Bhatti pays homage to an 18th-century Sufi mystic

Choreographer blends Kathak and contemporary influences in solo presented by the Dance Centre and New Works

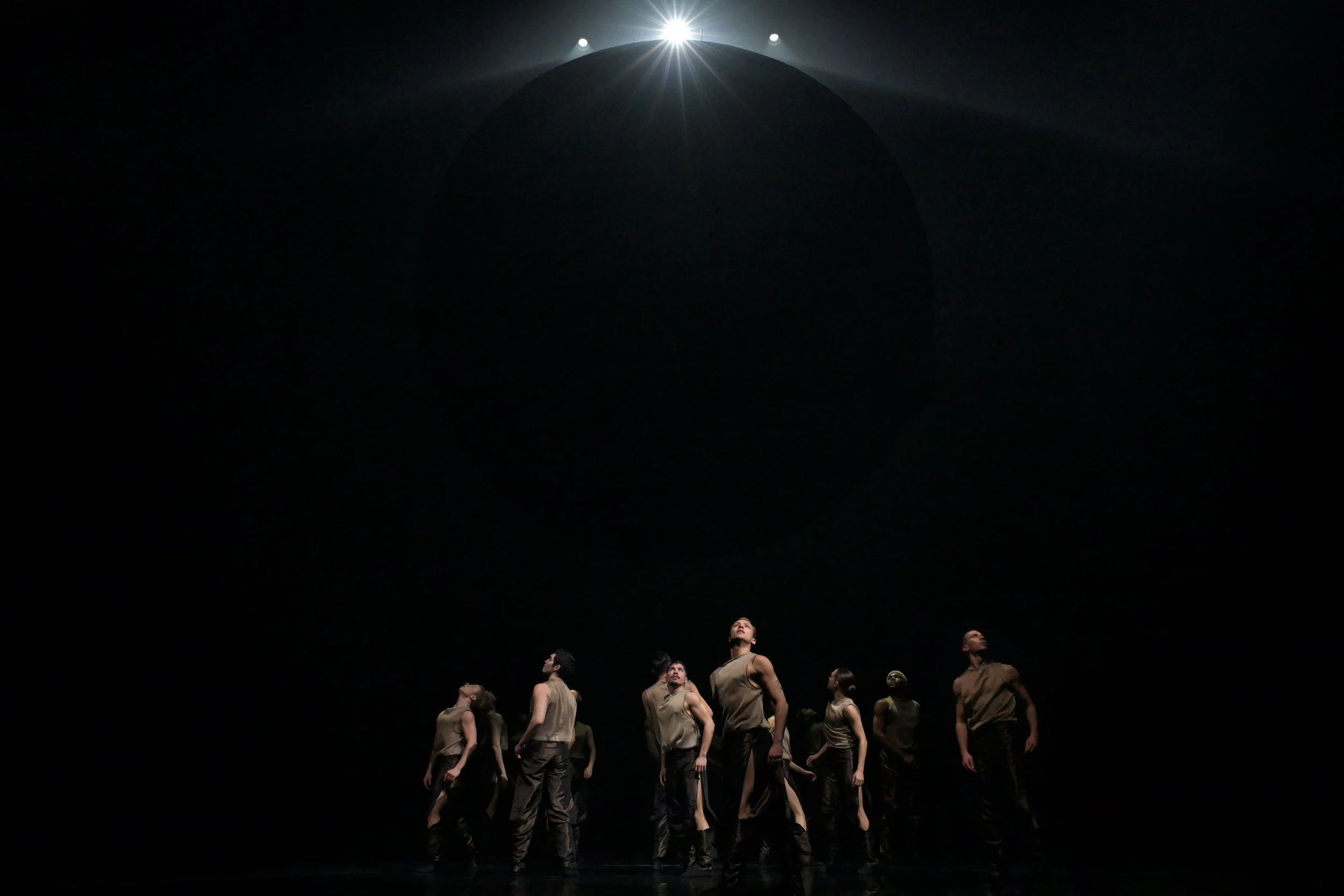

Gaurav Bhatti in Bulleh Shah: Seeker of Light. Photo by Innee Singh

Gaurav Bhatti. Photo by Innee Singh

The Dance Centre and New Works present Bulleh Shah: Seeker of Light at the Scotiabank Dance Centre on March 28 and 29 at 8 pm, as part of the Global Dance Connections series

KATHAK AND CONTEMPORARY dance artist Gaurav Bhatti’s latest solo draws inspiration from a powerful source: the teachings of 18th-century Sufi mystic Bulleh Shah.

Called Bulleh Shah: Seeker of Light, the solo’s titular poet and philosopher was widely revered for his thoughts on spiritual enlightenment. Most notably for the time, he advocated tolerance of human beings across all religions and social standings.

Speaking to Stir by Zoom, Bhatti shares that Bulleh Shah’s poetry questions several aspects of society. In one of the couplets the dance artist references, the mystic challenges people to consider whether there is any point to reading a thousand books and gaining knowledge externally without first looking inward and reading oneself.

“I really believe in the fact that Bulleh Shah’s teachings were about self-discovery, love, and building bridges between people’s hearts and souls,” Bhatti says. “Not just crossing bridges, but building bridges, and meeting at some point as well. And also while we meet each other, we’ll think about what is happening with us: What are we doing? Where are we standing? And why are we doing what we are doing?”

The world premiere of Bulleh Shah: Seeker of Light will take place at the Scotiabank Dance Centre on March 28 and 29, in a copresentation by New Works and the Dance Centre as part of the latter’s Global Dance Connections series. Drawing on a virtuosic combination of Kathak, Punjabi folk dance, and Western contemporary movement, Bhatti delivers his signature explosive energy while contemplating and embodying Bulleh Shah’s teachings.

Born and raised in the Punjab state in northwestern India, Bhatti came to Canada in 2006. While attending high school in Ottawa, one of his friends brought him to the Indian classical dance studio she practiced at, and he became hooked. But there was a minor issue: his parents, like many others in the Punjabi community, did not consider dance a profession.

Over the next few years, Bhatti took dance lessons in full secrecy from his family. A trip to Liverpool, U.K., to attend a workshop taught by some of the major gurus of Indian classical dance opened his eyes to the variety of styles at his disposal, from Kathak to Bharatanatyam. He soon committed himself fully to his craft, going on to study visual arts at the University of Ottawa and eventually sharing his dedication with his parents. His dance career has since taken him across the globe, from competing on the Canadian reality-television series Bollywood Star to performing an early version of Bulleh Shah at Dance Base in Scotland as part of the Edinburgh Festival Fringe.

Bhatti now splits his time between Vancouver and New Delhi, which is a main hub for Kathak. While in New Delhi, he trains with his current guru, Aditi Mangaldas, a leading practitioner of the style who runs the Aditi Mangaldas Dance Company and the Drishtikon Dance Foundation.

Mangaldas was Bhatti’s mentor for Bulleh Shah. With her guidance, Bhatti translated some of Kathak’s subtle gestures and inner workings into a more physically demanding and universally understandable movement language. The piece journeys through moments of innocence, searching, suppression, war, and peace.

“You know when you’re listening to music and it’s just serene?” Bhatti muses. “It’s like a sunrise in the morning. It’s beautiful, with trees and birds and flowers blooming, and you’re pure towards your devotion if you believe in God—you’re praying and you’re being repetitive. And then all of a sudden, something enters your body. It’s as if you were to pour a dark sort of ink in your cup of water, and then the colour changes completely. Then the darkness takes over, and it completely shakes you. So there is sort of the feeling of agony and inner turmoil.”

Gaurav Bhatti. Photo by Innee Singh

Bhatti is working with an international artistic crew for Bulleh Shah, including U.K.–based lighting designer Ryan Stafford, New Delhi–based sound designer and composer Ish Shehrawat, and Pakistani-Canadian costume designer Muhammad Alamgir.

His costume features the chikankari design, a traditional embroidery style that originates in the northern Indian city of Lucknow (which is where Alamgir sourced the fabric from, later sewing the garment in Toronto and Pakistan). The final costume has a special reveal built into it: as Bhatti sweats, a mesh layer made with the jali (net) stitch seems to become one with his body.

Just as Bulleh Shah mused about internal and external knowledge hundreds of years ago, the costume is symbolic of Bhatti bridging his innermost feelings with the outside world. And that connection carries over into how the artist hopes to reach audiences.

“My aim for Bulleh Shah was to bring Kathak dance with the Punjabi language to the Punjabi people of Canada and try to bring them out—give them a reason to come out, give them a reason to start connecting to the local scene,” Bhatti says. “Kathak, Indian classical dance, is seen by Punjabi people as not necessarily a career. It’s not necessarily a good thing, especially a boy wearing bells on their feet and dancing. So it’s me trying to make my space, but also trying to help people from the same country, from the same land, from the same roots, even though they’ve gone abroad…I would like to show them that there is another way of looking at how art could bring them closer to their ancestors, to their language.”

Bhatti adds that his practice comes down to creating acceptance within his community, and paving the way for kids in Canada to learn Indian classical dance if they so choose.

“No doubt that there is so much hard work,” he says. “There’s so much to sacrifice. I’m not saying that it’s an easy thing to do. But maybe if there are kids who are hiding just like how I used to hide and dance secretly, this becomes the voice for them.” ![]()