Stir Q&A: In James Kudelka's Half an Hour of Our Time, two dancers shift through heavy silence

Former National Ballet of Canada artistic director reflects on his 2008 duet as Plastic Orchid Factory gears up to present its revival

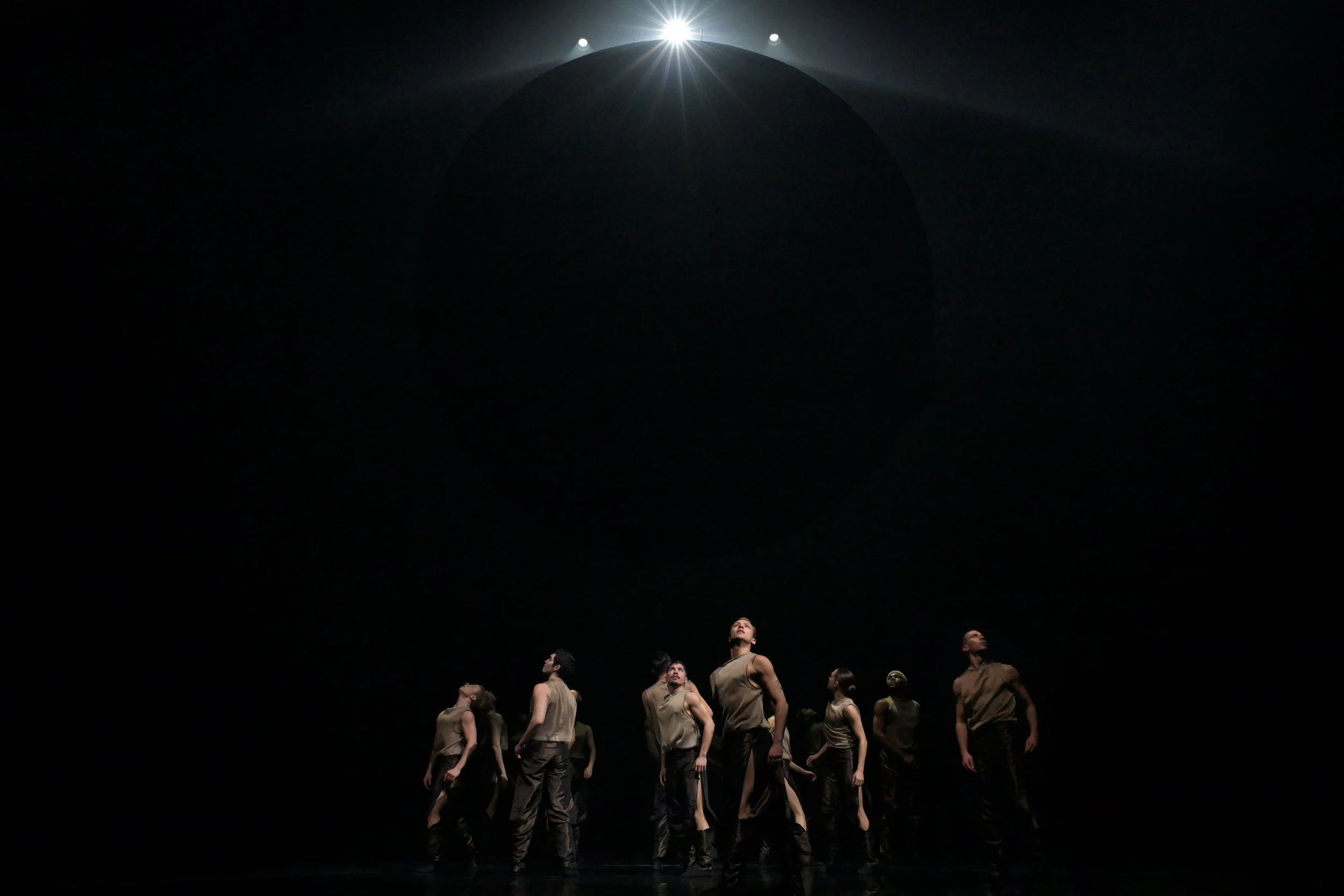

Half an Hour of Our Time. Photo by Jeremy Mimnagh

Plastic Orchid Factory presents Compagnie de la Citadelle’s Half an Hour of Our Time at Left of Main on April 17 and 18 at 7 pm

WORLD-RENOWNED CHOREOGRAPHER James Kudelka needs no bells or whistles to captivate audiences with Half an Hour of Our Time. Just 30 minutes long and performed in complete silence, the minimalist duet shows a couple’s life together unravelling onstage. And when it comes to Left of Main on April 17 and 18, less than a hundred people will get to witness each performance.

The backbone of the intimate work is Francis Poulenc’s one-act opera La voix humaine, which was based on Jean Cocteau’s play of the same name. In the simply designed opera, the libretto tells of a woman’s last phone call with her lover after he abandons her, following which she attempts suicide.

Kudelka is known for his work as a long-time dancer and choreographer for both Les Grands Ballets Canadiens and the National Ballet of Canada, of which he also served as artistic director from 1996 to 2005. He is an Officer of the Order of Canada and a recipient of the Lifetime Artistic Achievement Award at the Governor General’s Performing Arts Awards.

Half an Hour of Our Time was commissioned by Moonhorse Dance Theatre in 2008 and originally featured dancers Claudia Moore and Dan Wild. This revival is dedicated to the memory of Wild, who passed away in 2020, and features dancers Laurence Lemieux and Zhenya Cerneacov. It is produced by Compagnie de la Citadelle (of which Lemieux is cofounder and artistic director; Kudelka also served as resident choreographer there for more than a decade).

Ahead of Plastic Orchid Factory’s presentation of the work here in Vancouver, Stir connected with Kudelka to learn more about its origins.

What was it about Jean Cocteau and Francis Poulenc’s one-act opera La voix humaine that initially captivated you? Does the central phone call in the opera make its way into Half an Hour of Our Time, or have you taken a more abstract approach to the story?

The opera was a starting point, but I was not interested in any more than the drama. In the opera we don’t hear the voice of the lover over the phone. It is a one-sided conversation. In the dance I think we almost see the couple switch places, and we get more of the male dancer’s side of the story. In effect, he has the last word, unspoken. The dance was a commission from solo artist Claudia Moore. We were both at the National Ballet School in the same time period. Claudia was a few years off my own age. The duet is a result of being able to create very subtle situations and moods with experienced dancers. I needed a vehicle in which I could drive that pleasure. La voix humaine offered a context.

It’s rather unique for a dance piece to be performed in complete silence. Does that come with any logistical or artistic challenges? How does that simplicity within both the sound and set design affect the piece overall?

I have to try and remember what I was thinking. Answering these questions is an exercise in trying to create through cloudy hindsight what I might have been thinking while I was working. I did have a recording of the opera. At some point I must have figured out that it would be more interesting for me to work in silence. It was not, and would not be, the last time I chose that avenue of research. Around that time, I saw a work of Mark Morris’s called Behemoth, I think, that was a large-scale work in silence. I found it fascinating that a choreographer known for his musicality (as if none of us were as capable as he of being musical) to challenge himself in that way.

When I work in silence I am very aware that I am the composer, and that I have freedom that choreographers don’t have—being able to expand and contract time like a composer, but without the restraint of a score. A musical score will demand that you complete it. What a good musical score will do is often give the dance work an arc. At the time of Half an Hour’s creation, a lot of dances were created to musical mash-ups, and frankly few of them had less than three endings. I tried to create 30 minutes of material that had many scenes of different paces, but that through the relationship and the unspoken narrative of two bodies in time, and space, and facings, and shared weight, drove through time to an inevitable conclusion.

Given that you have choreographed a lot of large-scale productions over the years, especially for the National Ballet of Canada, what has it been like for you to work on such an intimate duet? Did you find you had to adjust your creative or choreographic process at all for this piece?

After creating 150 ballets I can safely say that there is no one, apart from me, who has seen them all. My full evening ballets for large-scale companies number only half a dozen of those 150. I worked in many venues with many kinds of artists. It made a lot of sense to me after stepping down from the directorship of NBoC to dig down to the roots of my practice and rediscover the joys of not having to keep a company of 60 dancers busy and in line. Working with Laurence at the Citadelle and with freelance artists like Claudia; collaborating with Art of Time; commissions from smaller ballet and dance organizations and Canada’s National Ballet School and the Arts Umbrella, were all part of my creative practice. I learned very early on to work with the dancer in front of me, be it in pointe shoes or bare feet, male or female, adult or child, and the company that commissioned or the organization I was running. Scale and size don’t matter. It is only important to get the most out of whatever situation I find myself in. Why create a solo to recorded music when you have a ballet company with an orchestra and a scene shop at your disposal? How much can I wring out of two exceptional bare-footed performers in a 60-seat theatre in silence? It is a challenge to be met to the best of my ability.

The premise of Half an Hour of Our Time is quite emotional. How would you describe each of the characters’ personalities? What does their story tell us about how heartbreak affects people—and about the importance of human connection?

The dance is about what the viewer thinks it is about. My themes are love, sex, and death, as were those of Martha Graham. I stand by them as the meaning of life and relationships. I try to create work that allows the viewer to think—to give enough information through the dancers and the movement choices so that the story is written by the viewer. I am not asking them to know my story.

How has Half an Hour of Our Time evolved since its premiere in 2008? What sense of purpose or meaning has dedicating this revival to the memory of Dan Wild provided for you and the performers?

To me, because the choreography, the moves, were so complex, I was myself amazed at the success Laurence had in recreating the dance. Laurence was the rehearsal director when the duet was created with Claudia and Dan in 2008. There were working videos, but only a dark and unfocused performance video taken from an angle at a dress rehearsal. I was not there when the reconstruction took place but I entered the process soon after, and as we worked I was able to recall aspects that were being lost. And it was very important to find the rhythms of the moves in the silence. Let the silence ring out in stillness, with just the sound of the dancers’ breathing.

Dan was quite a complex man. Not the healthiest person. A heavy smoker, and in fact I was a little afraid of him. Trying to recreate the male dancer in the dance reminded me of the challenge with many of my ballets, when a particular dancer cast in a creation creates such an impression and one doesn’t question it until trying to teach the role to someone else. The important part is for Zhenya to find his own performance through the moves that Dan fleshed out and interpreted.

I am very pleased that Half an Hour has had a rebirth. I think it can be seen now for the work that it is and not as a facsimile of its original performances with Claudia and Dan. But thank God for them, for having made it possible. It is a brain teaser memory-wise, a challenge stamina-wise, and not for the inexperienced. In dance these days, is it not rare to have a work from 2008 have a second life? ![]()