Through circus, Sacre reinvents Stravinsky's Rite of Spring

Australian contemporary-circus company Circa turns the ground-breaking work on its head

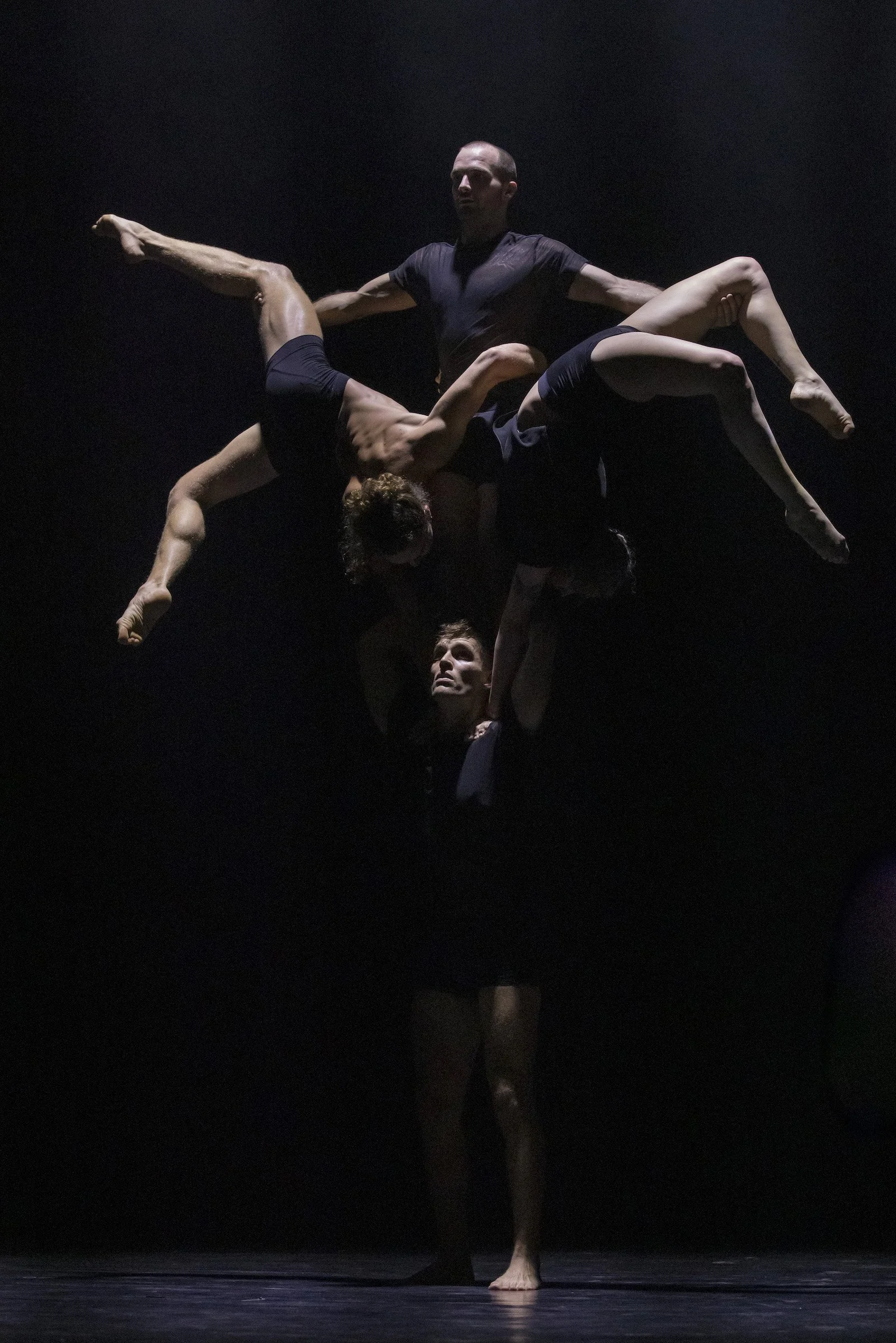

Circa, Sacre. Photo by Pedro Greig

DanceHouse and The Cultch present Sacre from January 17 to 21 at 8 pm at the Vancouver Playhouse

WHEN LES BALLETS RUSSES debuted Le Sacre du Printemps (The Rite of Spring) in Paris in 1913, a near-riot occurred. Igor Stravinsky’s brutal, dissonant score was unlike anything audiences had ever heard before, while Vaslav Nijinsky’s flat-footed, pigeon-toed choreography also came as a shock. Sacre is Australian company Circa’s interpretation of the seminal work, and while it isn’t leading to the kind of furor that broke out at Théâtre des Champs-Elysées 110 years ago wherever it travels, the show is causing a stir of its own: viewers have never seen anything like it.

Circa specializes in contemporary circus. Sacre draws upon the pagan myths and rituals referenced in Stravinsky’s Rite in which a young virginal woman dances herself to death. And Circa artistic director Yaron Lifschitz bases this altogether new version on the fiercely physical language of acrobatics.

As Vancouver will have the chance to experience when Sacre makes its Canadian premiere here courtesy DanceHouse and The Cultch this month, circus is an especially apt art form to breathe fresh life into the famous Rite of Spring, Lifschitz says in an interview with Stir. Connecting via Zoom from Circa’s Brisbane headquarters, the company CEO explains that “circus arts” has, for most of the genre’s history, been almost an oxymoronic term.

“It’s not really been an art form; it’s been a collection of performers and a high degree of artistry put together as entertainment,” Lifschitz says. “The difference between art and entertainment is that entertainment is concerned entirely with the level of pleasure felt by the spectator, whereas art attempts to reach for something terrifying, cathartic, and sublime.

“That’s changed in the last 40 or so years with groups like Cirque du Soleil…and independent artists that have all helped shift that ground, but at its core you can define circus as that historical medium in which a group of people gather and generally pay to see another group of people do things that the audience can’t conceive of doing themselves,” he says. “If you go to see Itzhak Perlman or Hilary Hahn, it’s extraordinarily virtuosic, but we can conceive what it’s like to play a violin. We can’t conceive of what it’s like to balance on someone’s head on one hand. The essence of circus is that it has in it something transgressive and boundary-pushing. As soon as it becomes commonplace it almost ceases to be circus.”

Yaron Lifschitz. Photo by Jessica Connell

As it continues to push the ever-evolving genre forward, Circa has performed across six continents in more than 40 countries to more than 1.5 million people since its formation in 2004. Having premiered in 2021 at the Illawarra Performing Arts Centre in Wollongong, Australia, the full-length Sacre features 10 acrobats and is set in part to an original score by French musician’s Philippe Bachman, which precedes Stravinsky’s ground-breaking composition. (LA Dance Chronicle described Bachman’s music as lying “somewhere between human voice and percussion”, and as having a “mysterious alienation that invites you in.")

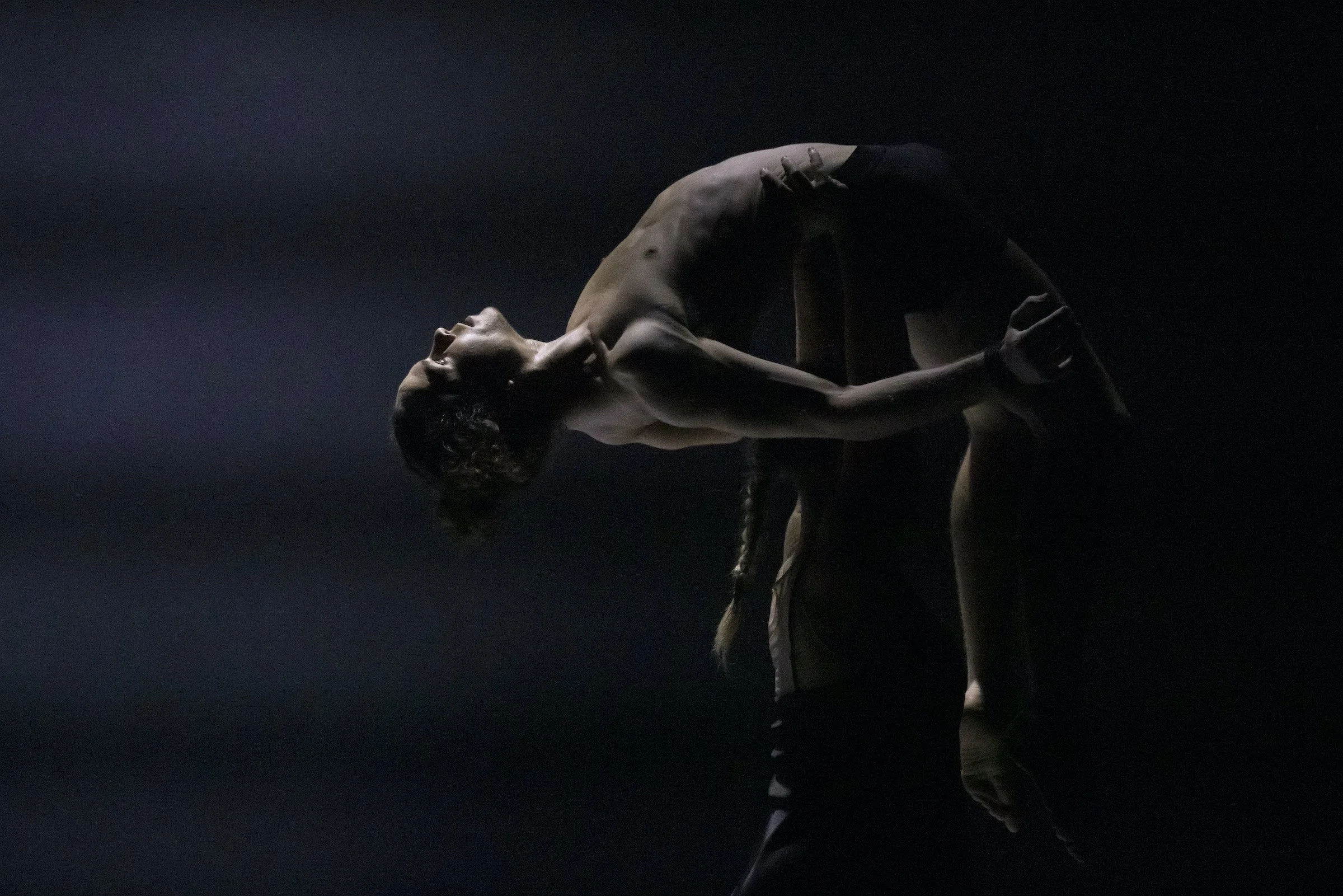

As the performers climb atop each other, leap, tumble, and contort, Sacre’s primal drama is heightened by Veronique Benett’s lighting design in the form of a single, stark fixture.

Intensity is very much what Lifschitz is going for. He was inspired by Pina Bausch’s 1975 Rite of Spring, which he considers a “transcendent masterpiece”. Sacre explores themes of sacrifice, sexuality, and divinity; it also looks the roles of the individual and of the group in community and connection.

For Lifschitz, working on Sacre has only reinforced for him the power and beauty of circus. Having studied theatre, Lifschitz was the youngest director ever accepted into the National Institute of Dramatic Arts’ graduate director’s course. He also has experience working in opera and puppetry, on large-scale events, and in museums and other cultural institutions.

“I trained as a theatre director,” Lifschitz says. “I make plays, and I was unsatisfied with the experience of people talking to each other, trying to create meaning by acting….I realized that theatre at some point had got hijacked by literature and had become kind of a department of schools of English in its essence, and in a sense that was exactly what I didn't want to do even though I have a couple degrees in literature. There’s nothing wrong with literature; it just wasn’t the kind of authentic experience I was after or was looking for.

“The acrobatic language we use is very strong, very physical; this is one of the hardest shows we’ve done,” he adds. “It’s very raw and very rough. It’s one of those circus shows where no one claps during the show—people often tell me they didn’t feel they could really breathe; they were holding a lot of tension in the body. I like that. I’m a big fan of theatre when it’s a phenomenological experience rather than a kind of intellectual one, something that you feel. This is like treating yourself to a really good gym session—it’s hard but it feels great afterward.”

Circa, Sacre. Photo by Pedro Greig