Coastal Dance Festival work salutes matriarch who helped keep a culture alive

Dancers of Damelahamid’s Margaret Grenier is still waiting to gather to celebrate her mother Margaret Harris’s life, but in the meantime, she’s creating a dance

Dancers of Damelahamid are known for innovations on Northwest Coast traditions that could have been lost but for the efforts of elders. Photo by Chris Randle

Margaret Grenier was awarded the Walter Carsen Prize earlier this year.

Dancers of Damelahamid present the Coastal Dance Festival from March 12 at 9 am to March 18 at 9 pm via Vimeo

ACROSS THE PLANET this pandemic year, properly grieving the loss of a loved one has been difficult because of the ban on social gatherings. It’s proven particularly painful for dance artist Margaret Grenier.

The artistic and executive director of Dancers of Damelahamid lost her mother Margaret Harris—a central force in the revitalization of coastal dances—in July. The Gitxsan community would usually go through a structured process of ceremonies to mark the loss.

“To be so restricted made it a strange year for grounding ourselves and finding a way to move forward,” reveals Grenier, who was also faced with the loss of a brother last month. “It feels like a holding pattern is taking place until we can celebrate her life, especially because she was so connected to the community….I became aware of why we have memorials and feasts and all of that.”

Adding to the sense of loss is that the Harris matriarch was, at 89, one of the last of her generation in the family. Predeceased by her husband, Chief Kenneth Harris, in 2010, she was a keeper of culture who helped revive once-banned dances, stories, and songs through the founding of Dancers of Damelahamid—the company Grenier leads in Vancouver today.

Only a handful of Grenier’s immediate family was able to gather when her mother died. But the artist is creating a new dance work to mark her life, an excerpt of which will premiere on film via the free online Coastal Dance Festival that Dancers of Damelahamid has hosted for 14 years.

“It’s to serve us personally but also to create something that will carry her presence forward,” the artist explains, adding the vision is to build it into a much bigger work once dancers can gather more freely in the studio again.

Called Raven Song, the piece is sung by Grenier’s daughter Renée and danced with the Raven mask. “The lyrics do speak about the presence of someone who passes and also will be there to guide us when it’s our time to pass into the spirit world,” Grenier explains.

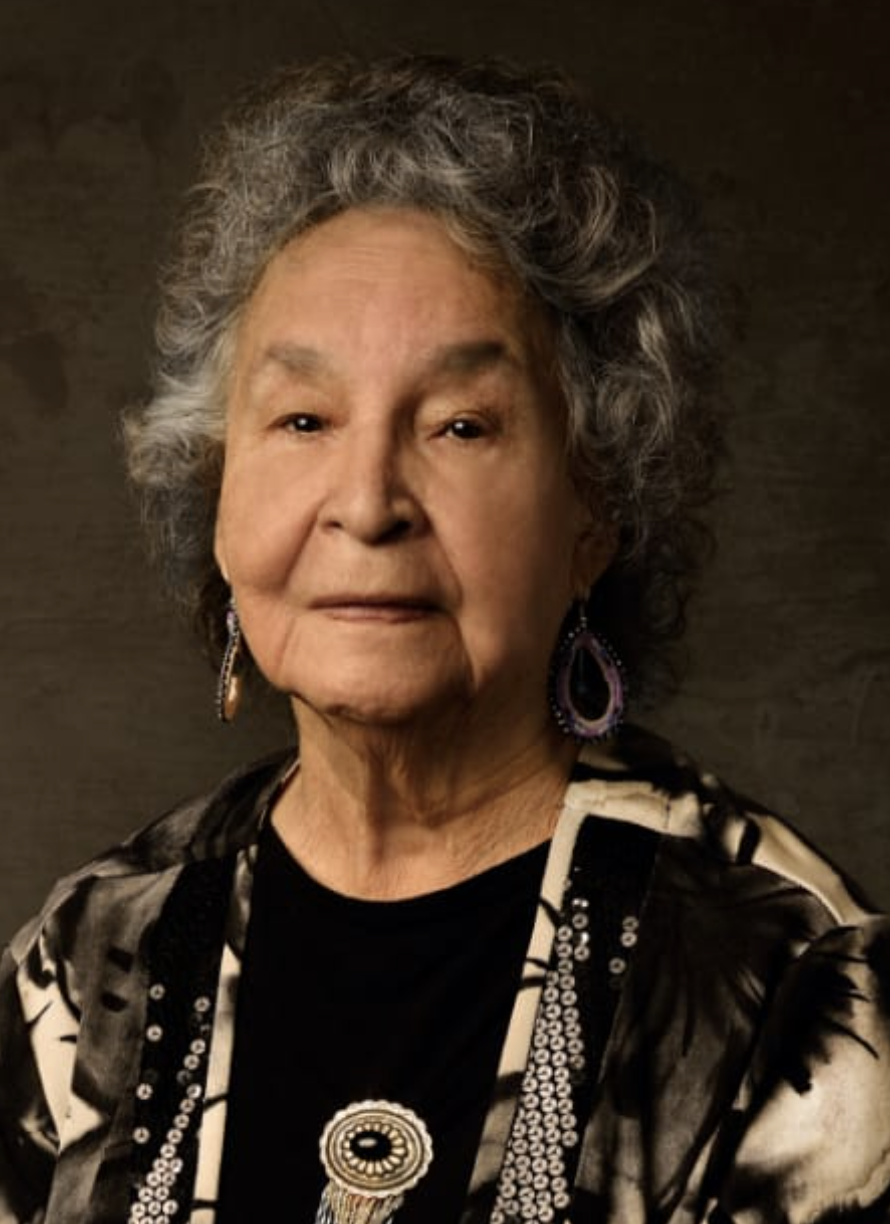

The late Margaret Harris.

The title is a nod to her mother’s unique history. Born in 1931 in Churchill, Manitoba, and raised as a Metis member of the Cree Nation, she was adopted into the Raven clan in 1953, when she married Gitxsan chief Harris, leader of the people who live along the Skeena River in northwestern B.C.

“Her [dance] training was something she was immersed into when she married my father,” Grenier says. “It really was reflective of her personality: someone who has the strength and personality to step into a culture that's very unique. And that’s something I’ve always found remarkable.”

In fact, there is much more that’s remarkable about how Grenier’s predecessors were able to keep their culture alive amid the potlatch ban that outlawed their practices from 1884 to 1951.

“My father never went to residential school himself, and he was trained not only by his mother but also by his grandparents as well,” Grenier relates, “so he had a really strong grounding in language and knowledge.”

Grenier credits Kenneth’s mother, Irene Harris, for a pivotal role in the survival of the dances, songs, and stories. “She had incredible foresight,” Grenier says. “She was born in 1882 and passed in 1972, so the majority of her life was affected by the potlatch ban. She was already in the later part of her life when the potlatch ban lifted….But she had the foresight to support my parents by documenting the knowledge.”

Incredibly, Irene Harris and great-uncle Arthur McDames recorded songs and stories on an old reel-to-reel tape, using pots and pans instead of the traditional banned drums, all in an effort to create some lasting document of their culture. “To have that archive and vision really guided my parents,” says Grenier, whose mother purchased her family’s first drum from a collector when the potlatch ban was lifted.

Her parents’ dance troupe’s first performance was in 1967, outside a feast hall in Prince Rupert for the Ha Yaw Hawni Naw Salmon Festival. That group would grow into Dancers of Damelahamid, and go on to tour the country, and as far away as Japan and New Zealand.

Grenier, the youngest in the family, feels fortunate to have grown up steeped in that culture.

“As a very young girl, I was really blessed, because anyone 10 years or older than me would have a memory of not dancing, and then dancing again,” she says, referring to the lifting of the potlatch ban. “I’m at the right age of going back to my earliest memory, my family was performing and dance was taking place in the community.

“I grew up in something very solid and very connected,” she adds of her years being raised near Prince Rupert. “I always had that connection to a living practice. It grounded me in an identity that was connected to these stories and songs and dances—and those stories always have a connection to a land and place.”

Still, Grenier says it wasn’t until she left home, to study at the postsecondary level in Montreal for five years in the 1990s, that she really started to appreciate that training—and to miss her culture.

“When I was in Montreal, there was a lot that influenced me because it’s a very vibrant and accessible arts community in Quebec,” she recalls, “but at same time what I had taken for granted all my life was my community and practice of dance, which you don’t really think about as a teenager.”

Grenier was also deeply influenced by returning here briefly to perform with her parents’ company in Vancouver dance artist Karen Jamieson’s seminal Gawaii Ganii—a 1991 collaboration that took Indigenous dance tradition into the realm of contemporary dance, with a performance at the UBC Museum of Anthropology.

“It was a different way for our family to engage in collaboration and how it was presented,” she says.

In 1997, Grenier moved back here full-time, pursued her masters in education at SFU, and started setting the stage to take the reins of her parents’ company in 2003. Her goal? To respectfully bring old traditions into a new age. The first performance, notably at the Scotiabank Dance Centre, was her own choreography, Setting the Path. “It was sort of a pivotal transition, where my parents were singing and engaged but had moved over to being elders and mentors,” she says.

In the ensuing years, her company has become known for boundary-breaking hybrids of traditional and contemporary dance, often with cutting-edge multimedia touches, such as the video-projection-driven Flicker and Mînowin.

Alert Bay’s Yisya̱winux̱w Dancers appear at this year’s online fest. Photo by Amanda Laliberte

Grenier’s achievements raising the profile of Indigenous dance in the broader dance and arts community were made obvious last fall, in one of the year’s few high points, when she was awarded the Walter Carsen Prize for Excellence in the Performing Arts. She was the first Indigenous artist to win the biennial award since it was established in 2001.

At the same time, Grenier has worked to build the Coastal Dance Festival, which Dancers of Damelahamid founded in 2008. The event returns in an online pandemic rendition this week, instead of its usual live gatherings at the UBC Museum of Anthropology and New Westminster’s Anvil Centre.

This year’s fest features video performances from Whitehorse’s Inland Tlingit Dakhká Khwáan Dancers, Kitsumkalum’s Git Hayetsk Dancers, Washington-based Git Hoan Dancers, Squamish’s Spakwus Slolem, Alert Bay’s ‘Yisya̱’winux̱w Dancers, and Alaska’s David Robert Boxley. Grenier’s new Raven Song was filmed at the Anvil.

As ever, Grenier prefers to emphasize the diversity of Indigenous cultures on display, as much as the connection between them.

“There are so many stories of loss and so many stories of disconnection that I think that, rather than us seeing cultural sharing as sort of leading to a pan-Indigeneity, that we see that the more different voices we can add to this conversation, the more clear we can be about these languages,” she says.

The world closed down right after the dance festival last year, and the ensuing months have been difficult for Indigenous communities—many of them still unable to gather on any large scale to practise their culture. Organizing this year’s online fest, Grenier has been reaching out to groups across B.C. and the West Coast, and finding many at different stages in the vaccine process.

That they are continuing to find a way to dance and sing at all reminds her of the resilience of Indigenous culture—the same strength and connection her late mother encouraged.

And in that way, the entire festival, as well as Raven Song, can be seen as part of Margaret Harris’s legacy—one her family and community can hopefully celebrate soon in the largest social gathering possible.