Curve! exhibition celebrates women Indigenous carvers on the Northwest Coast

The new show at Audain Art Museum sheds light on the artists who are less-known than their male counterparts

Dale Marie Campbell, Woman who Brought the Salmon, alder, pigment, abalone. Private Collection. Photo by NK Photo

Audain Art Museum presents Curve! Women Carvers on the Northwest Coast until May 5, 2025

INDIGENOUS WOMEN OF the Northwest Coast have long carved masks, poles, canoes, bowls, and panels, yet they are generally not nearly as well-known outside their communities as their male counterparts. A new exhibition at the Audain Art Museum seeks to change that.

Curve! Women Carvers on the Northwest Coast is co-curated by Dana Claxton—an artist, filmmaker, and head of UBC’s department of art history, visual art, and theory—and Curtis Collins, the AAM’s director and chief curator. The exhibition spans more than 125 works, including poles, panels, masks, bowls, and other sculptures on loan from public and private collections across Canada and the U.S. by 14 artists. The show focuses on carvers active from the 1950s to the present day, highlighting the vital role that women artists have played within the broader tradition of Indigenous carving of wood and argillite along the coast of B.C.

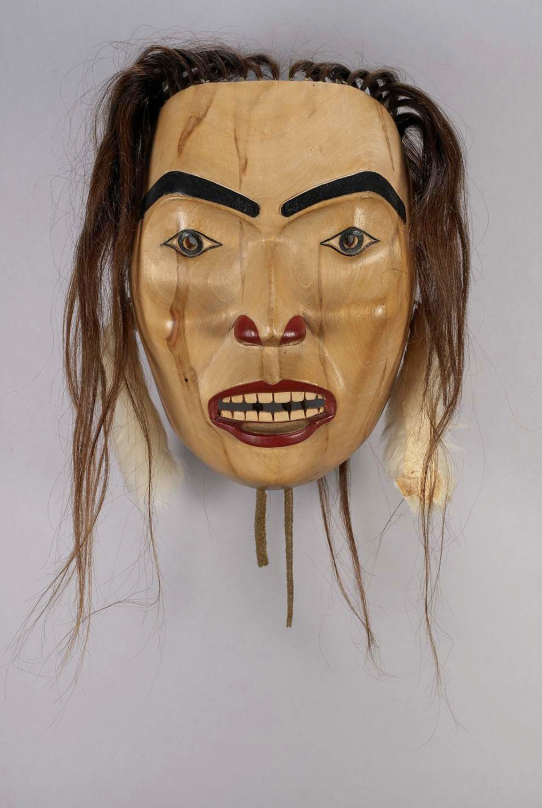

Doreen Jensen, Novle Woman with Labret, 1980, popular, human hair, rabbit skin, pigment. Courtesy the Museum of Anthropology, The University of British Columbia, 2635/1. Photo by Derek Tan

“Carving was traditionally a male practice and to a certain extent it remains a male-dominated practice,” Collins says in an interview with Stir. “During the post-war period, that’s when we see the emergence of women carvers, so this show really examines what I would refer to as the contemporary tradition of Indigenous women up and down the coast. Women were traditionally more involved in weaving whether it was woven hats or blankets, but this movement by these artists that are featured really strikes a new moment in Indigenous art history on the coast. We both find that a really fascinating prospect.”

Ellen Neel (1916-1966), Freda Diesing (1925-2002), and Doreen Jensen (1933-2009) are three iconic artists of the Northwest Coast who serve as historic context for the show. Their trailblazing work paved the way for subsequent generations of carvers. Neel, a Kwakwa̱ka̱ʼwakw artist from Alert Bay, was the first woman in Canada to be recognized for carving totem poles professionally. Diesing, a revered Haida artist from Prince Rupert, studied at the Vancouver School of Art and the Gitanmaax School of Northwest Coast Art and became a mentor to icons like Robert Davidson and Dempsey Bob. Jensen, a Gitxsan artist of the Fireweed Clan, was born in Kispiox near Hazelton and was known for her advocacy in promoting Indigenous art and revitalizing traditional practices.

The exhibition features artworks by Susan Point, a descendent of the Musqueam peoples; Tahltan-Tlinget artist Dale Marie Campbell; and Marianne Nicolson of the Musgamakw Dza-wada’enuxw First Nation, who together represent accomplished senior artists. Marika Echachis Swan, who is of Tla-o-qui-aht, Nuu-chah-nulth, Irish, and Scottish descent; Morgan Asoyuf, who is a member of the Ts’msyen Eagle Clan; Haida member Cori Savard; Stephanie Anderson, who is of the Wit’suwit’en Nation; Veronica Waechter, who is of Gitxsan and European settler descent; Arlene Ness, who is of Wilp Tsi Basaa-Git Luxhl Lim Het’Wit; Cherish Alexander, whose home community is Gitwangak; and Haida artist Melanie Russ are mid-career and emerging artists in the show who continue to push the realm of carving forward.

Susan Point, The First People, 2008, red and yellow cedar. Collection of Seattle Art Museum, Margaret E. Fuller Purchase Fund, in honour of the 75th Anniversary of the Seattle Art Museum, 2008.31. Photo by Nathaniel Wilson

Collins says that during the Dempsey Bob show at the AAM, the Tahltan-Tlingit artist spoke about the tremendous impact that Diesing had on him and his career and the resurgence of carving in general. Dieseing and Jensen were both active as teachers, with the Freda Diesing School of Northwest Coast Art at Coast Mountain College being an important educational institution where many of the carvers in the show studied—while Neel sold carvings of miniature poles and masks out of Stanley Park.

“The vast majority of works in the show, particularly masks, are women representing women,” Collins says. “There’s a salmon woman, moon woman, goat woman—so there are all these female faces that surround you as you move through the four gallery spaces that make up the whole show. There is a preponderance of masks but there are also rattles, poles, frontlets, plaques… It’s mostly carving in cedar both yellow and red as well as alder and also argillite. It’s a nice variety of materials and formats and even the range of nations that are represented I would hope are quite impressive.”

Freda Diesing, Old Woman with Labret, alder, cedar bark, human hair, abalone shell, pigment. Audain Art Museum Collection. Purchased with funds from the Audain Foundation, 2020.005. Photo by Kenji Nagai

Monumental works include a full-scale pole by Neel called Totem Pole, from approximately 1950 to 1955, the earliest piece in the show, and a wall piece by Point titled The First People made in 2008 of red and yellow cedar. Among the pieces by Diesing are Old Woman with Labret from 1973, made of alder, cedar bark, human hair, abalone shell, and pigment; and Shark Woman Mask, also from 1973, made of alder, human hair, argillite, and pigment. Jensen’s pieces include Noble Woman with Labret from 1980, made of popular, human hair, rabbit skin, and pigment; and Soap Berry Spoon 1 and 2, made of red cedar, also from 1980. Campbell’s Woman who Brought the Salmon—from 2021 and made of alder, pigment, and abalone—is among the signature pieces for Curve!, as it captures the relationship between humans and animals so central to Indigenous beliefs.

Accompanying the exhibition is a hard-cover book published by Figure 1 featuring texts by Claxton—who won the 2023 Audain Prize for the Visual Arts—Swan, and Skeena Reece and interviews by Collins with Campbell and Mary Anne Barkhouse. It has images of more than 100 artworks spanning over 75 years of artistic production.

Ellen Neel, Totemland, c. 1965, wood, pigment. Collection of Dana Claxton. Photo by Kenji Nagai

Swan helped Collins and Claxton with protocol and put together a narrative based on quotes by the artists that flow through the exhibition and provide perspectives on the practice of carving.

“The interesting thing for Dana and I with this show is that it is well overdue,” Collins says. “The fact that the Audain Art Museum is the generator of this exhibition bodes well for museum in terms of setting a national standard and seeking out areas in which we can represent ourselves as a leader and recording important moments in art history, not only in British Columbia but I would say Canada and even internationally. The show is very contemporary. We deliberately avoided any anthropological overtones in the presentation of this work, which can be problematic in the treatment of contemporary Northwest Coast art.

“I think it all underlines the fact that we’re a little museum that does big things,” Collins adds. “I really think this is a very special moment in the museum’s eight-and-a-half year history—that we’ve become the pacesetter in British Columbia and Canada in terms of looking at areas like this that have been not given their proper recognition.” ![]()