Dance review: Ballet BC's Take Form shows the troupe members in a different light

From powerful duets to surreal visions, mixed program gave an up-close new look at the company

Passing By by Justin Rapaport. Photo by Four Eyes Portraits

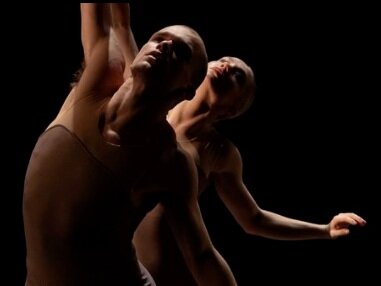

Passing By by Justin Rapaport and Overcasr by Kirsten Wicklund. Photos by Cindi Wicklund

IT WASN’T SUPPOSED to look like this. Ballet BC should have been debuting new work on the Queen Elizabeth Theatre stage, showing off the vision of a new artistic director, and preparing for tours around North America and Europe.

What we got instead from the company this week was a streamed program of nine short works created by and for its dancers and artists-in-residence, encouraged by artistic director Medhi Walerski. (The troupe had to pivot quickly, after his own creation, to be performed live to a socially distanced audience at the Polygon Gallery, was postponed and then cancelled last month due to the province’s ongoing arts-performance shutdown.)

Proving great creativity can emerge from limitations, the show called Take Form provided new insights on, and a new appreciation for, the honed members of Ballet BC. There is some real choreographic talent emerging from the corps, but that’s not really a surprise: many of its members have spent years working closely with some of the top visionaries in the world. Veteran company dancer and artist-in-residence Peter Smida did a crack job of camerawork, and the pro hands of costume designer Kate Burrows and lighting designer James Proudfoot added extra finesse.

It should be noted that, unlike so much dance we’re seeing now, this show went beyond duets and solos into group work. Late in the fall, health officials decided to treat the ballet members like the legit professional athletes they are—not fitness-class-goers or hobbyists—allowing them to work in a strict bubble together. That added to the range and movement the choreographers could explore here.

Highlights of the one-night-only program included the opening five-hander, the beautifully innovative Semble, by Jacob Williams—made all the more amazing by the fact that he’s an emerging artist who’s joined the troupe from Arts Umbrella. It opened with a brilliant trompe l’oeil overture, the dancers’ bare shoulders, heads, and hands popping in and out of the dark in kaleidoscopically surreal and disembodied formations. Hands might emerge on either side of a face, clenching it and pulling it back into the void, or a pair of feet might somehow descend down above a head. That gave way to amorphous, shifting sculptural formations—at once organic yet mechanical and herky-jerky, bodies suddenly pulled back by some unseen force. I loved the angular play of bent elbows and knees here, especially in Rae Srivastava’s solo, a study in focus and control. (He’s another exciting emerging artist: this bodes well.)

Another standout was Kirsten Wicklund’s powerful pas de deux Overcast. The longtime Ballet BC dancer has been making a splash with her choreography on local stages, and she’s developed a distinctive voice. Think classical technique, but supercharged and devoid of frailty. The brilliance here is the perfectly matched pairing of Jordan Lang and Parker Finley, muscular dancers in identical beige bodysuits, Finley en pointe. Arms slice the air and backs ripple, but the piece finds incredible strength in still poses as well. Set to the flickering electronica of Ben Foster, Field Works, and Loscil, the partnering is dazzling. At one point he goes from hoisting her upside down to horizontal over his shoulder then upright above his head—but not at lightning speed, so it seems even more physically punishing.

More striking partnering came from dancer Justin Rapaport, whose Passing by featured sibling Evan Rapaport and Srivastava, circling like whipsaws, twining and untwining. Something about the piece, with the men in their sad, ripped business suits, spoke to the toll the pandemic is taking right now—people trying to make a living, or struggling with job loss or even depression. From the opening, in which the men would pass repeatedly, only bumping, to moments where they would support each other, to the ending’s final tender act of simply laying their heads on one other’s shoulders: the choreographer and his expressive dancers imbued it with a humanity that resonated deeply.

I could go on. The two overriding impressions from the show were the physical chops and versatility of the corps right now, and of the diversity of vision of the people creating the works. On one end of the spectrum you had the emotionally charged pairing of Jordan Lang and Alexis Fletcher’s if we were to meet, giving way to Livona Ellis’s clever self-reflective duo The Valenced Other, with its inventive floorwork and chair play, and to Stefanie Noll’s magnetic dancing and creative editing in Double Self Portrait. On the other end, you had the bouffon-vaudeville touches of Brandon Alley’s solo This and That, the surreal caught-in-a-TV imaginings of Smida’s an untimely and abbreviated errand, and Zenon Zubyk’s darkly humorous and clubby Denial of My Skeleton.

Take Form offered a rare up-close-and-personal look at the dancers--several of them new faces. That should enrichen our experience of watching them show their considerable stuff where they belong, across the expanse of the Queen E. stage--whenever the pandemic gods decide that will be.