Doug and the Slugs get their due as true Canadian legends in new DOXA documentary

In which filmmaker Teresa Alfeld helps a former doubter find a fevered appreciation for one of Vancouver’s most misunderstood bands

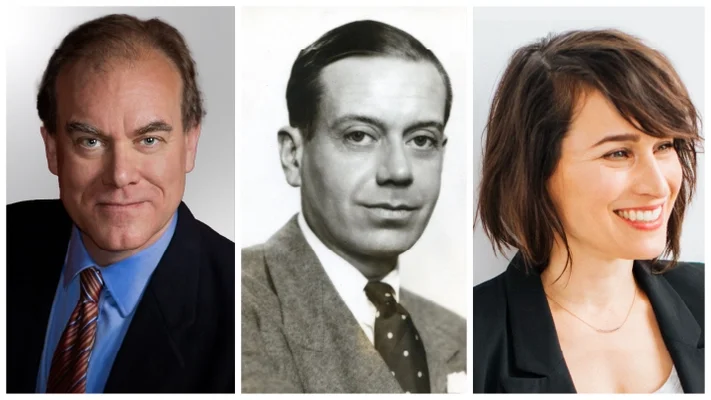

Filmmaker Teresa Alfed (pictured with the Bennett sisters) grew up in East Van next door to lead singer Doug Bennett’s household.

Doug and the Slugs and Me closes this year’s DOXA Documentary Film Festival at the Vancity Theatre on Sunday, May 15

IN THE SPIRIT of Teresa Alfeld’s very personal new film, I’ll add myself as a character to this article and declare that Doug and the Slugs and Me demolished 40-plus years of antipathy I’d felt towards the band.

I could appreciate that hits like “Too Bad” and “Real Enough” defined a certain flavour of early ‘80s Canadiana, and it was impossible to deny their buoyant personality and craft, but to use the British expression, I thought they were a bit naff. In short, I’d dismissed Doug and the Slugs as a novelty act.

Alfeld’s connection to the band goes back to childhood—in the early ‘90s she lived next door to vocalist Doug Bennett’s lively family home on Semlin Drive, where she became besties with his daughter Shea—but she sympathizes.

“I understood Doug and the Slugs as that sort of comedy thing,” she tells Stir, reached at her home in Vancouver. “Personally, that didn’t appeal to me so much either when I was younger. But when I really started researching the band, when I sat down with all their records and listened to them front to back, I was floored.”

Well, yes, exactly. Her born-again enthusiasm is infectious.

Doug and the Slugs and Me is peppered with deeper Slug cuts—“Chinatown Calculation”, “Dangerous”, “Wrong Kind of Right”—that work like little subliminal programming cues, emphasizing the band’s amazing agility and the uncommonly sharp and literate musical inventions of singer-composer Bennett. I was lining up the records on Spotify and falling in love and kicking myself after one viewing.

Says Alfeld: “Doug and the Slugs created, especially with those first few albums, some really distinctive, complex, sophisticated music. But this is not what we think when we think of Doug and the Slugs. We think of all the sex jokes in ‘Making it Work’. So that’s one thing that I’m really hoping people get from this film, that this is a catalogue of music that deserves a second look beyond just the hits.”

A feast of archival footage and the singer’s extensive journals make the new documentary Doug and the Slugs and Me much more than a straightforward story of the rise and fall of one of Vancouver’s best-known bands.

As a rock doc, Alfeld’s film delivers everything you’d expect with a feast of archival footage (Vancouver in the ‘70s and ‘80s never ceases to fascinate), along with contemporary interviews—including all the surviving Slugs: guitarists John Burton and Richard Baker, keyboardist Simon Kendall, bassist Steve Bosley, drummer Wally Watson—and the contributions of supporting players like former MuchMusic VJ Michael Williams, who recalls his time doing double duty as the Pointed Sticks tour manager and the East Coast distributor for Vancouver label Quintessence. It was through his efforts that Doug and the Slugs scored their first hit in 1980 with the independently released “Too Bad”. It’s a reminder that Doug and the Slugs might have been victim to lingering subcultural prejudices and some revisionist history over the years, and I’ll cop to that. There’s an aura of legend attached to their colleagues in the historic Vancouver punk scene, who never came within spitting distance of the Slugs’ popularity and chart success, but it seems to have eluded Bennett and his partners, no?

Alfeld isn’t sure. “They’re certainly remembered for their off-the-wall warehouse shows that they used to put on, not unlike D.O.A., bands that were too outsider to get booked in the clubs, and who had personalities like Doug Bennett who said ‘Fuck it, let’s do it ourselves.’”

There’s no disputing that Doug and the Slugs came “super close” to the U.S. breakthrough that benefactors like Sam Feldman (also interviewed in the film) believed was within reach. Sadly, their commercial success in Canada was impressive but never quite enough, and the band was eventually consumed by mainstream ambition, along with debt and internal tensions, mostly over Bennett’s autocratic domination of the project. He was a man restlessly spilling over with ideas. (Among the discoveries Alfeld made during her research: Bennett planned to go to film school but his student loan never turned up. The band would win a lot of attention from the videos he conceived and directed.)

Significantly, she began the film thinking it would be a straightforward chronicle of the band’s rise and fall, which, as these things tend to go, ended with Bennett’s declining musical fortunes and health, leading to his death in 2004 at the age of 52. Then Bennett’s widow Nancy handed her the singer’s extensive journals, and suddenly, as alluded to by the Slugs old tour manager Joe Jackson, it was like Doug was directing from beyond the grave.

“Everything changed when I got my hands on those journals,” Alfeld says. “And once I read them, beginning to end—holy shit. This felt like sitting down and having a conversation with a big figure from my past.”

She subsequently called on Bennett’s friends, colleagues, and family to read significant passages from the journals on camera, in turn lending the film one of its most memorable and painful moments. Bandmate John Burton was the first to join Bennett on his mission back in the ‘70s, but they also had the rockiest relationship, and the guitarist is visibly shaken to read aloud Bennett’s blunt assessment of their growing estrangement. Alfeld gives “huge credit” to Burton for going through with the exercise, which is mirrored in the film’s tentative and poignant reuniting of Alfeld with her old pal Shea, and the grief they share over personal losses.

Undoubtedly, it’s fair to say that Doug Bennett was one of those inspiring freaks of nature who galvanized (and vexed) the grown-ups who fell into his creative orbit. Bob Geldof offers fond memories of his rascally colleague at the Georgia Straight in the early ’70s, where Bennett put his artistic gifts to use as a political cartoonist. Burton also provides the best line on his old partner, saying the weirdo he first encountered at a party in the mid-70s looked like “a seedy bohemian used car salesman.” (Totally true.)

To Alfeld, however, Doug Bennett wasn’t a hitmaker or showman or a seedy bohemian or anything else besides her best friend’s dad and “a goofy guy in a goofy shirt who used to chase us around the yard with a turkey on his head.” Or perhaps he was more than that? The film includes an intimate scrap of history almost too good to be true: a snatch of home video from a family visit to the Grandview Lanes in which we hear Doug Bennett instructing his infant daughters to hand the camera to Teresa, who’s wobbling around the bowling alley at a bare 30 inches tall. Is it fanciful to suggest that Alfeld’s future career stars here? She laughs. “Ya know, I’d love to give Doug that credit.”