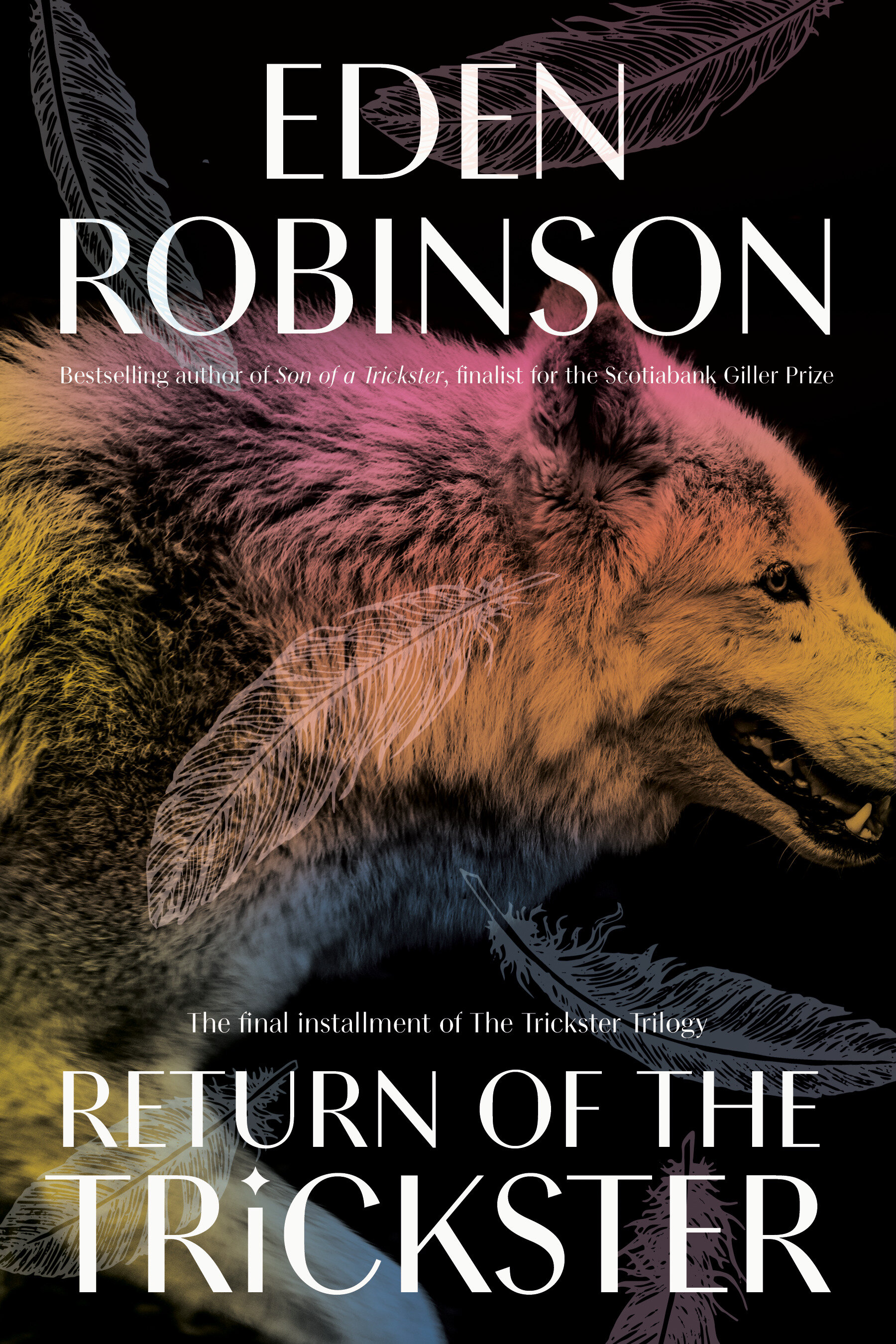

Eden Robinson's Return of the Trickster goes to supernatural war

The writer from the Haisla and Heiltsuk First Nations cites Stephen King as an influence

Writer Eden Robinson says the horror genre helps her make sense of the world.

EDEN ROBINSON’S COVID-19 isolation and her love of horror almost led to the gory deaths of all the main characters in the third and final installment of her Trickster trilogy.

During an interview with Stir, the Haisla and Heiltsuk author from Kitamaat Village explains that she wrote the second draft of Return of the Trickster (Penguin Randomhouse)—which follows 2017’s Son of a Trickster and Trickster Drift from 2018—amid the loneliness and uncertainty of self-isolation. (She had been in contact with someone who had potentially been exposed to the novel coronavirus.) In that version of her highly anticipated novel, “everybody died.”

She dove into the next draft after her quarantine ended. It was then that the her highly anticipated new book truly began taking shape.

“The third draft is more of the novel that’s out there now,” Robinson says. “It’s gruesome and it still reflects a lot of that headspace, but it’s toned down a lot.”

Return of the Trickster continues and concludes the series surrounding teenager Jared Martin, the Trickster. The story resumes just hours after the end of Trickster Drift and follows Jared as he finds himself in the middle of a supernatural war.

Robinson says she gets a lot of her inspiration from the horror genre, including author Stephen King, but while her novels have horror elements, they also have “Eden humour”. “There were always these incredibly absurd moments that surprise you and you laugh,” she says.

During a conversation in which the Eden humour shone through, with her quick wit and infectious laugh, Robinson explains that she discovered her passion for writing in her teens.

“When I discovered writing, I fell in love with it because I could tell stories, but I could edit them until they were good,” Robinson says. “That was a revelation. I knew quite early that I loved reading, but I didn’t know until high school that I loved writing.”

After one of her short stories was read out loud to her high-school class, Robinson says that she never felt cooler. It was during this period—which was a difficult one—that she began writing short horror stories and fan fiction.

“When I was around age 13, I had my first depressive episode,” Robinson says. “Back then, you didn’t talk about it. You didn’t admit to any kind of depression. I found that a lot of the stories that they gave you in high school did not reflect the reality that I was experiencing. But horror really encapsulates what it’s like to be depressed—that kind of dread and fear. It just resonated with me.”

Horror will always be a part of her writing, she says, especially during a time when there is a tremendous amount of injustice in the world. Horror has become her way of grappling with things she cannot control.

Her love of storytelling is also inspired by her family and Indigenous culture. She comes from a family of storytellers. When she began the Trickster series, she wrote it with them in mind as the target audience, so that they could see themselves reflected in her story. However, while her relatives and friends have influenced the development of some of her characters, she says they are not solely based on them.

“They give a lot of inspiration, but I find it hard to work with real characters,” she says. “When I write a character that is solidly based on someone, they’re kind of limited to what that person did. I find it hard to make them do things that are outside of the character that I know in real life.”

With respect to the cultural influence on her writing, Robinson explains that when it came to Haisla stories, she wanted to ensure she was respectful.

“When I was writing Monkey Beach [2001], I didn’t understand that some stories are only for us, and some stories can be for other people,” she says. “The concept of story ownership is very different, and it’s attached to the potlatch.”

As a result, she writes about stories in the Haisla public storytelling domain; this is where the Trickster stories lie. The stories of Tricksters were used to teach children and “were meant to be funny and wild.”

(Robinson’s Trickster series had been adapted to a CBC television program but was cancelled after its second season following controversy surrounding producer Michelle Latimer’s claims of Indigenous identity.)

Robinson compares her feelings on concluding the Trickster trilogy to that of a break-up. While writing the novels was a long, lovely journey, she says it’s time to move on.

“There’s many novels that I want to write, but I’m just not there yet,” she says. “I’m still in the ice-cream eating stage.”