Dance review: Live audience goes wild for Ever So Slightly's timely hip-hop-infused metaphors

On-stage musicians add to a piece that finds Montreal’s RUBBERBAND in visionary form

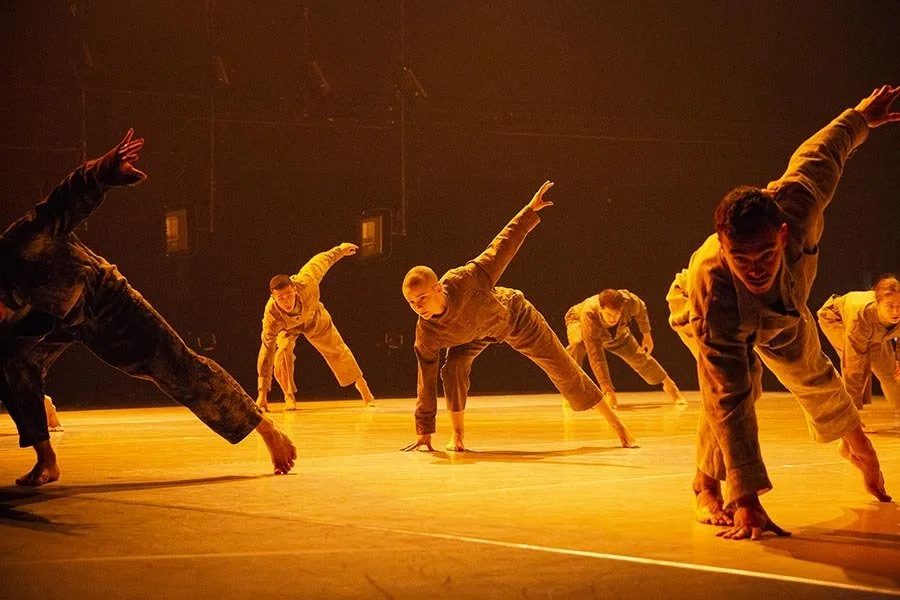

RUBBERBAND’s Ever So Slightly. Photo by Marie-Noële Pilon

DanceHouse presents RUBBERBAND’S Ever So Slightly at the Vancouver Playhouse to October 23

AT THE OPENING night of Ever So Slightly this week, normally reserved Vancouver arts fans leapt to their feet for some of the wildest applause that’s ever followed a contemporary-dance show here. It felt like collective catharsis, after watching 10 performers connecting on-stage in front of a sizable live (masked and double-vaxxed) audience—following 19 months of pandemic withdrawal.

Montreal’s RUBBERBAND, finally returning to the DanceHouse program after having the production postponed in March 2020, had the unique distinction of becoming the first large-scale dance company to take the stage this fall.

And it lived up to the expectation with choreographer Victor Quijada’s most ambitious work yet. With Ever So Slightly, he takes the vocabulary of hip-hop into bold and innovative new places—into graceful balletic formations, and into deep and sometimes disturbing emotional terrain.

Quijada is schooled as much in the LA streetdance scene as in the contemporary ballet of Twyla Tharp and Les Grands Ballets Canadiens; about 15 years ago, he was also a magnetic force in Crystal Pite’s Kidd Pivot work Lost Action. Here, his choreography is at its most mature and visionary, employing a larger-than-usual ensemble that’s uniquely trained in his hybrid style—one that’s less about power moves than seamlessly flowing drops, flips, and kip ups into contemporary dance.

Take Ever So Slightly’s opening sequence, where 10 dancers in coveralls come to life on the floor like gently rolling waves, their slo-mo downrocking becoming hypnotic poetry. Heightening the scene, as they do the entire performance, are live multi-instrumentalists Jasper Gahunia (DJ for hip-hop artist K-OS) and William Lamoureux, creating an aural dreamscape with haunting violin and guitar from risers at the right of the stage.

From here, the music revs up, lights flare, and electric guitar and beats sound, as the troupe forms a sort of society, and all the struggle and revolution that entails.

Sometimes they stand watching and doing nothing as a person suffers; at others, they try to hold down a man thrown into wild panic. The idea of consuming and rejecting our own finds its most wildly physical embodiment in a scene where dancers shoot like rockets into the air, firing straight up and out of a seething mass of bodies.

But what sets Quijada’s work apart is its more quiet and vulnerable moments--the kind you don’t necessarily associate with the energy of hip-hop. On the other hand, Quijada doesn’t hold back when the corps breaks into a brawl that feels brutally real, the dancers pummelling and flailing at each other, screaming and shrieking in animalistic rage.

There’s anger, pain, and distress, but there’s fun here too. Some of the most inventive work comes as the crew strips each other to underwear, pulling off the boiler suits in a crazy-flowing ballet of yanking, kicking, twisting, dragging, and rolling.

The flow of vignettes can feel loose and abstract, even managing to work in a scene that feels like a B-boy battle, each dancer one-upping the other.

But it all flows toward a finale where that competition, struggle, chaos, and conflict dissipate and the corps comes to embrace what feels like change. The dancers converge in a final transcendent moment of connection--spinning, lifting balletic beauty under rose-hued light before the stage goes dark. Quijada had never heard of COVID when he created this piece. But unintentionally, his work has taken on striking new metaphorical value for an unprecedented era of upheaval and pain, and—one can only hope—transformation.