Plastic orchid factory's fever dreams book captures dancers' reflections on a surreal year

Through photos, poetry, drawings, and essays, a community chronicles a new kind of creative process

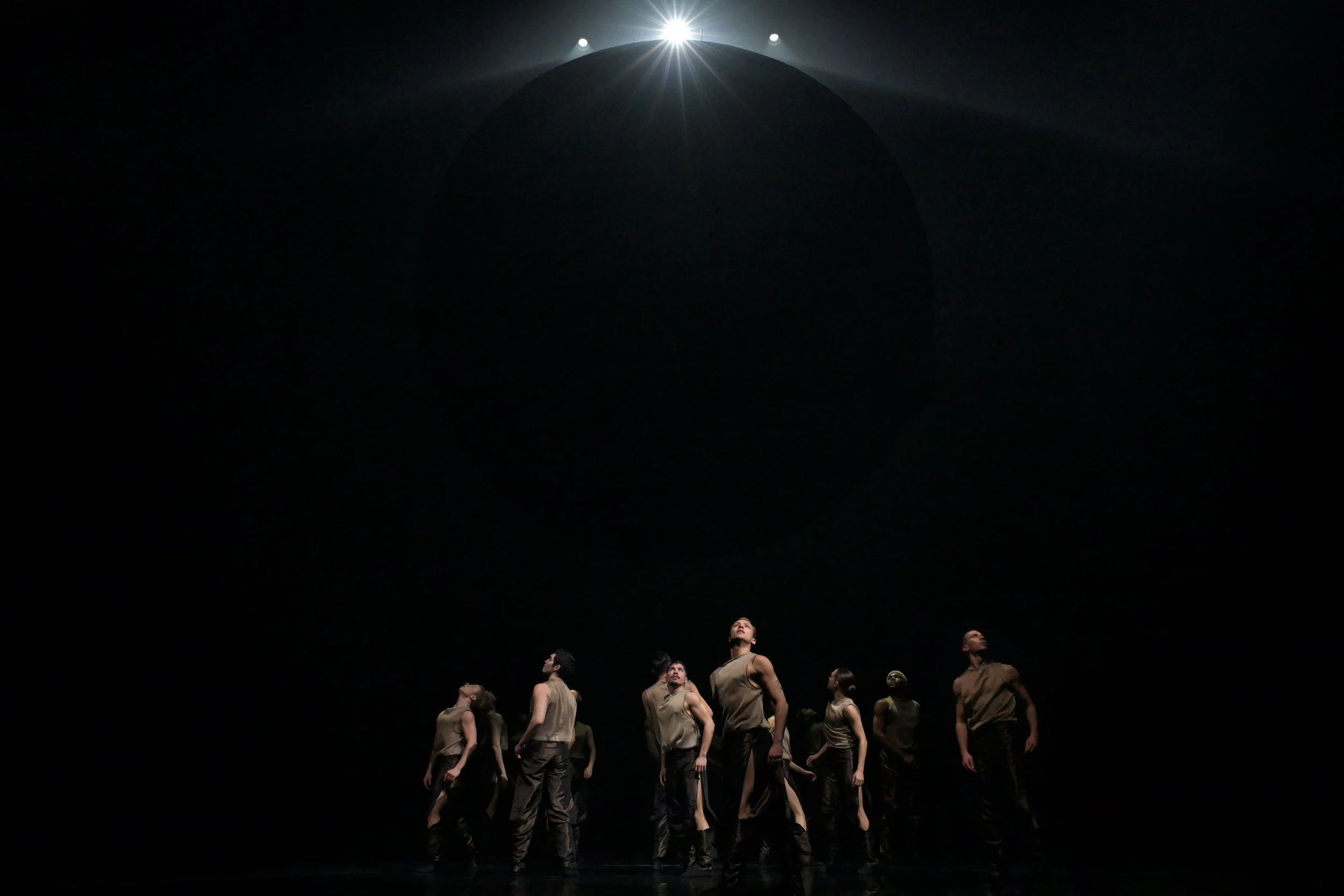

Fever dreams documents an early stage of the pandemic, when plastic orchid factory and friends could only gather to dance in Vancouver parks. Photo by James Gnam

FACED WITH A year of dance going through drastic change, Vancouver’s plastic orchid factory decided to capture what was going on through the medium of print.

That project has now grown into fever dreams—a small soft-cover book of essays, poetry, illustrations, and photos that artfully encapsulate dance creators’ reflections through this year.

It features submissions from 22 artists who are either presenting streamed shows during plastic orchid factory’s online dance season (like Deanna Peters and Less San Miguel) or who have had residencies at the company’s Left of Main studio, including Livona Ellis, Zahra Shahab, Rachel Maddock, Francesca Frewer, and Erika Mitsuhashi.

Realizing a lot of those artists’ work would never reach an audience in the 2020-21 season, artistic directors James Gnam and Natalie LeFebvre Gnam set out to print “something tangible that we could affordably and safely share with a public”, the latter explains.

The book, given extra aesthetic flourish by Montreal’s Julie Espinasse of Atelier Mille Mille, includes a digital version posted on plastic orchid factory’s website.

The title fever dreams caught the entire mood of the year, the duo behind it explains.

“That’s what it all sort of felt like at the time,” explains Gnam, sharing a call with life and work partner LeFebvre Gnam. “Donald Trump was still president, and all that craziness was there. And then being locked in our house and asking, ‘Am I really going to spend $25 on toilet paper?’

“Then as we were trying to wrap up, the whole world caught fire, and we were living in a haze,” he adds of the forest-fire smoke that choked the West Coast last fall. “It felt like the end of days—except not sexy like in the movies!”

“It was definitely surreal,” adds LeFebvre Gnam.

Producing the book was the result of a long, and sometimes difficult, journey for the pair—one that reflects the collective struggle of an art form that has been particularly gutted by the pandemic. Dance is about everything that’s taboo amid a contagion: breathing and moving together, touch, sweat, and connection.

Rachel Maddock working alone at Left of Main, in fever dreams. Photo by Deanna Peters

Rewind to the beginning of March 2020, and the duo was getting ready to move themselves and their two sons to Berlin for an artistic residency. They were supposed to fly out March 12 and made the difficult decision, like so many other travellers, to cancel.

“We had this really exciting opportunity—but it turned out to be just the first of many cancellations and disappointments, and then recalibrations and adaptations,” says Gnam, who would also have toured France, dancing with Montreal collaborators later in the year. (He’s also an associate artist with the Quebec city’s MAYDAY and Grand Poney.)

Suddenly, the two found themselves in lockdown at home with a three-year-old and a teen doing online school. Their studio, Left of Main, an artists’ hub and studio-performance centre in a former upstairs Dim Sum joint in Chinatown, was shut down until the summer.

For the past few years, the plastic orchid factory artistic directors had been on overdrive. In 2017, it had pursued the permits and overseen the redevelopment of the Chinatown space that houses the big studio, as well as headquarters for Action at a Distance, CADA/West, MascallDance, and Rachel Meyer. Plastic orchid factory had been hosting a full roster intimate shows at the space, when it wasn’t being used for rehearsals.

All that came to a halt for a few months. “We eventually realized the best approach was patience,” explains LeFebvre Gnam. “We’re both energetic types, and this was, ‘No, you have to just wait.’”

The turning point, chronicled in fever dreams through photography and text, was when the pair started to dance again in early summer—outdoors in Quilchena, Pacific Spirit, and Jericho Beach parks with some of their close colleagues. “It was a rekindling of what dance could be,” LeFebvre Gnam says. “For me, personally, it was the realization, ‘Oh my god, I need this so badly: to dance, to share time together.’ For sure I cried every day!”

Rejuvenated, the couple went back to work, investigating how to get people back working inside the studio at Left of Main, with safety front of mind. They worked out a system of booking exclusive weeklong “bubbles” of dancers, with a cleaning crew sweeping through after each residency.

At the same time, the duo started planning a season with a few streamed shows. And fever dreams grew out of a sort of printed program for both what artists were experimenting with in the studio, and what would be offered online—what the pair calls “the incubative and the adaptive” work happening out of Left of Main.

The call they put out to artists for the book had no parameters: artists could express themselves through writing, illustrations, or whatever form they felt would best capture their thoughts.

The resulting project somehow quantifies the unquantifiable—the inner explorations of artists working in an ephemeral art form, in a suspended time.

And so, beside an image of dancer Avery Smith you’ll find such poetic lines as “Transmit telepathic secrets to yourself. Whisper them to the shallow crevasses of you./Tie down the ephemeral and ask its name. Watch the concrete fly away and evaporate.”

Juxtaposed with Sarah Wong’s paintings of fleeting, watery blue imagery, and a photo of an abandoned billboard whose blue ocean scene is peeling off and folding in on itself, are thoughts like “Future dreaming seems irrelevant but the impossibility of it makes it that much more dreamy.”

And for Gnam’s own pages, pictures feature him rehearsing his new work, Solo, in a gas mask and hooded jacket (the piece debuts May 23 to 29 online). “The solo that I was working on was slowly becoming my life,” he writes in an essay. “I was in it. My kids were in it. My partner was in it. My neighbours and friends were in it and we all played parts in a six month long fever dream where hours blended into day and days into weeks and weeks into months.”

The experience of recasting their season and collecting submissions for the book have made the folks at plastic orchid factory acutely aware of how hard the pandemic has been on the city’s dancers.

An image from Zahra Shahab’s contribution in fever dreams.

“That first lockdown was hardest for most people in the dance community,” Gnam recalls. “For the first time in many, many years they weren’t practising with other people—because it is at its core a social art form. We were all sort of feeling exposed nerves and everybody just took time to take care of themselves and their practice.”

On the flipside, LeFebvre Gnam adds, dance is needed more than ever, as a way to help articulate and work through the heavier emotions the pandemic has brought. “It has such a profound communication that can have an impact on audiences,” she says. “It’s sort of the way bees communicate: it’s this other way. And I think people are missing that.”

On the more positive side, fever dreams’ writing and imagery look toward a brighter future. If the book reveals anything, it’s that a lot of exciting new ideas are incubating and waiting to express themselves again.

“When we have herd immunity, we have a bunch of artists who have been really thinking for a year about what they do and why they want to do it,” says Gnam. “And there’s going to be a lot of amazing art that’s being made.”