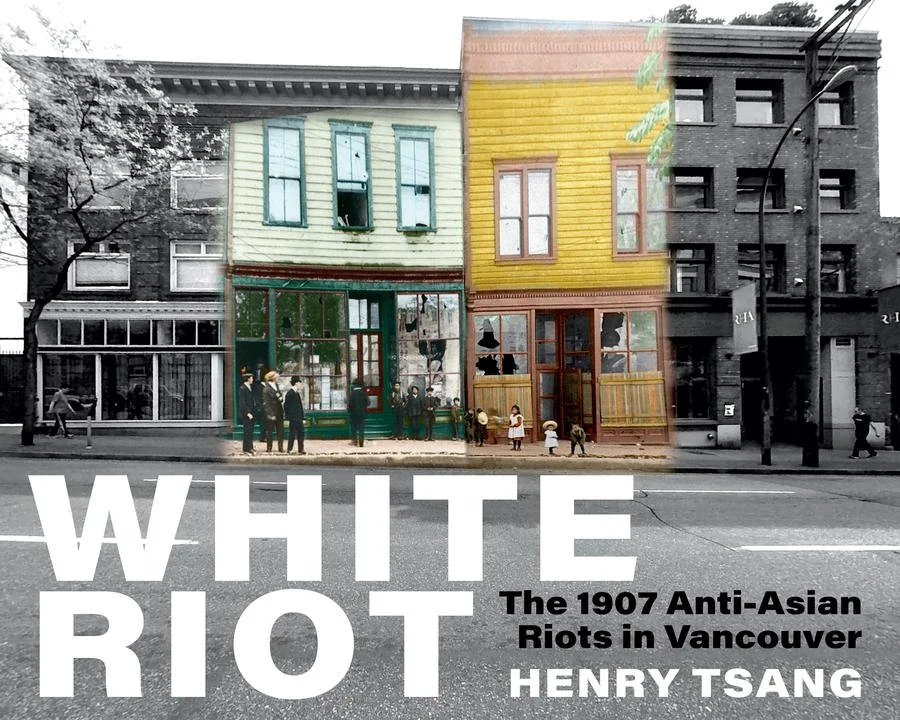

Henry Tsang’s White Riot documents a shameful episode in Vancouver history

Vancouver artist’s new book grew out of a walking tour that revisits sites of 1907 anti-Asian violence

IN 1907, IMMIGRATION was a hot-button issue in Vancouver—especially when it came to new arrivals from Asia, whose very presence threatened the ideal of Canada as a “white man’s country”. The newly formed Asiatic Exclusion League (among the founders of which were Mayor Alexander Bethune and several city council members) organized a rally and parade for September 7 of that year. Thousands gathered at the old market building, which once stood on Main Street next door to the Carnegie Centre and served as City Hall at the time.

Incendiary speeches stoked an already fiery crowd, and when someone (variously described as “a boy” and “an unruly teen”) hurled a brick through a window, that proved to be the spark that ignited a couple of days of rioting. The mob swarmed Chinatown, smashing additional windows and causing many thousands of dollars in property damage to Chinese-owned businesses.

By the next day, the rioters were advancing on the Japanese neighbourhood at Powell Street. With the advantage of having had the better part of a day to prepare themselves, residents there were better able to fend off their assailants, and the riot eventually fizzled out.

While it’s surely one of the most shameful episodes in Vancouver’s history, many who live in the city have only the haziest recollections of learning about it in social-studies class—if they were taught about it all.

“There are people who have no idea that this riot happened here, and these are people who were born in Vancouver and went through the school system,” says local visual and media artist Henry Tsang. “There are still kids who are going through the school system and it hasn’t been introduced to them. You know, it all depends on the social-studies teachers. So, some kids have been introduced to this, but again it’s voluntary from the point of view of the educators.”

Henry Tsang.

To help redress this knowledge gap, Tsang, who is also associate dean and a professor at Emily Carr University of Art and Design, launched a project called 360 Riot Walk in 2019. On the tour, participants are directed to 13 stops in and around Chinatown, where, through interactive 360-degree video technology, they learn about the events and context of the 1907 riots via their own mobile devices.

Although the 360 Riot Walk was designed to be self-guided, it has also been presented as a guided group tour during the warmer and drier months. (After watching at least one tablet get destroyed by Vancouver rain, Tsang cautions against completing the walk in inclement weather.) In the summer of 2022, however, taking a group through certain parts of the Downtown Eastside became impossible as a tent city sprung up and its residents tussled with police officers tasked with clearing it away. Because the 360 Riot Walk is situated in a neighbourhood with a high density of vulnerable and marginalized people, Tsang recommends that participants take a companion along and treat the residents of the DTES with respect and courtesy.

“There are insensitive visitors who go down there for poverty tourism or something weird, and people get really upset if they think you’re taking their picture, so be polite and show them what you’re looking at and say, ‘This is an art project,’” he advises. “And usually people are okay after that.”

For those who are unable to undertake the walk in person, it is possible to view it on their web browser at home, albeit without the full functionality of the “gyroscope” that makes it an immersive experience. Tsang says he and his tech team are planning to roll out “virtual tours”.

In the meantime, there is also a forthcoming book, White Riot, which Arsenal Pulp Press will release on April 4.

White Riot includes imagery from the walking tour along with the full text of its voiceover script. The book also features a number of insightful essays that place the events of 1907 into historical context and examine the ongoing impact of anti-Asian racism.

“When I built out the website I invited some people to do some writings to further contextualize the topic, and then I also built out a series of panel discussions,” Tsang says of the book’s genesis. “And all around that I was thinking it would be nice to have something that isn’t going to be obsolete in a few years because of technological changes. And I love books. I’ve always loved books. There’s a lot of pictures here, and I had some writings already. I already wrote some stuff myself and I thought, well, it would be nice if there was a book. So here we are, a couple years later.”

As any serious student of history knows, examining the events of former times through a modern lens can shed light on the roots of the problems that plague society in the present. While 1907 might seem like the impossibly distant past, the topic of anti-Asian racism—which reared its shameful head in a significant way in the wake of the COVID-19 pandemic—is all too contemporary.

“This kind of awareness helps us understand how things got to the way they are today—that there is a historical precedent for the anti-Asian violence that has bubbled forth and hurt a lot of people,” Tsang says. “It’s still in people’s hearts and minds because they have this attitude that some people are less than human, or that they have the right to inflict their violence and anger on others; that they have more rights than others.

“Why is it important to know our history? Well, if we don’t know our history, we can’t move forward—because it does define our place and time.”