Dance review: Hourglass is a poignant exploration of passing time

Wooden chairs, breathtaking honesty, and Philip Glass’s 20 Piano Études

Hourglass. Photo by Chris Randle, Dancer Kate Franklin

The Chutzpah Festival presented Hourglass at the Norman and Annette Rothstein Theatre on November 5 and 6

WHILE TIMING IS A frequently considered component of dance work, seldom is it brought to an audience’s attention in such a stunningly conceptual fashion.

A work by Israeli choreographer Idan Cohen developed from the music of Jewish composer Philip Glass’s 20 Piano Études, Hourglass is a poignant exploration of passing time that encapsulates the shared human experience of aging, with all its ups and downs.

Divided into five acts—Childhood, Love, Adulthood, Epilogue, and The Last Étude—Hourglass employs a cast of eight dancers, ranging in age from early teens to late 60s, in order to bring the audience on a journey through time.

The curtains open onto a cleverly crafted set by Amir Ofek that piques the interest immediately. Centre-stage, a man (Will Jessup) outfitted in a blue sweater vest and slacks sits on a wooden chair with a large cardboard box in his lap. Behind him, white sheets are draped over various props around the stage as if they’re in storage, creating an eerie air of abandonment. High above, a rectangular frame hangs from the rafters with a wooden chair inside it. In the upstage right corner, Vancouver-based conductor-musician Leslie Dala is poised behind a grand piano, ready to play through Glass’s work live.

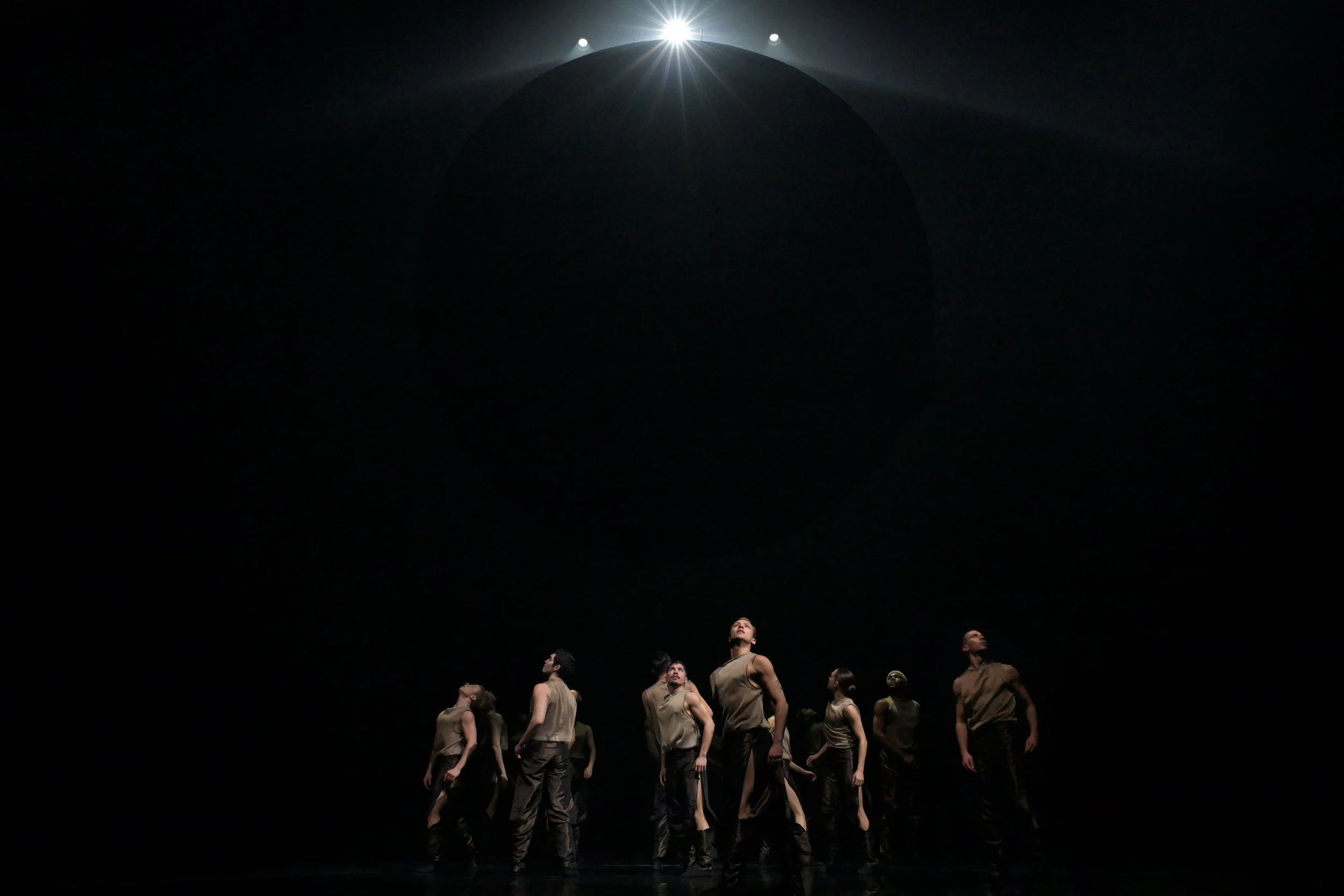

Dancers begin moving around the set, dressed in billowing white garments with ghastly hair and makeup. These haunted figures start peeling the sheets off of props. To the audience’s surprise, there are more dancers under the sheets, blending in against the sharp edges of furniture.

As the show gets underway, it becomes clear that the audience is reliving Jessup’s character’s memories. We are introduced to a cast of colourfully outfitted characters: Jessup’s younger self, a boy dressed identically to his adult counterpart, who rolls a toy truck around; his romantic interest, who eventually becomes his wife and the mother of his child; and his parents, whose communications with each other are often riddled with arguments.

Costume design by Christine Reimer, with the assistance of Charlotte Chang, truly helps to differentiate the slumbering recollection of the dancers outfitted in white from the active memory of those who are colourfully clothed.

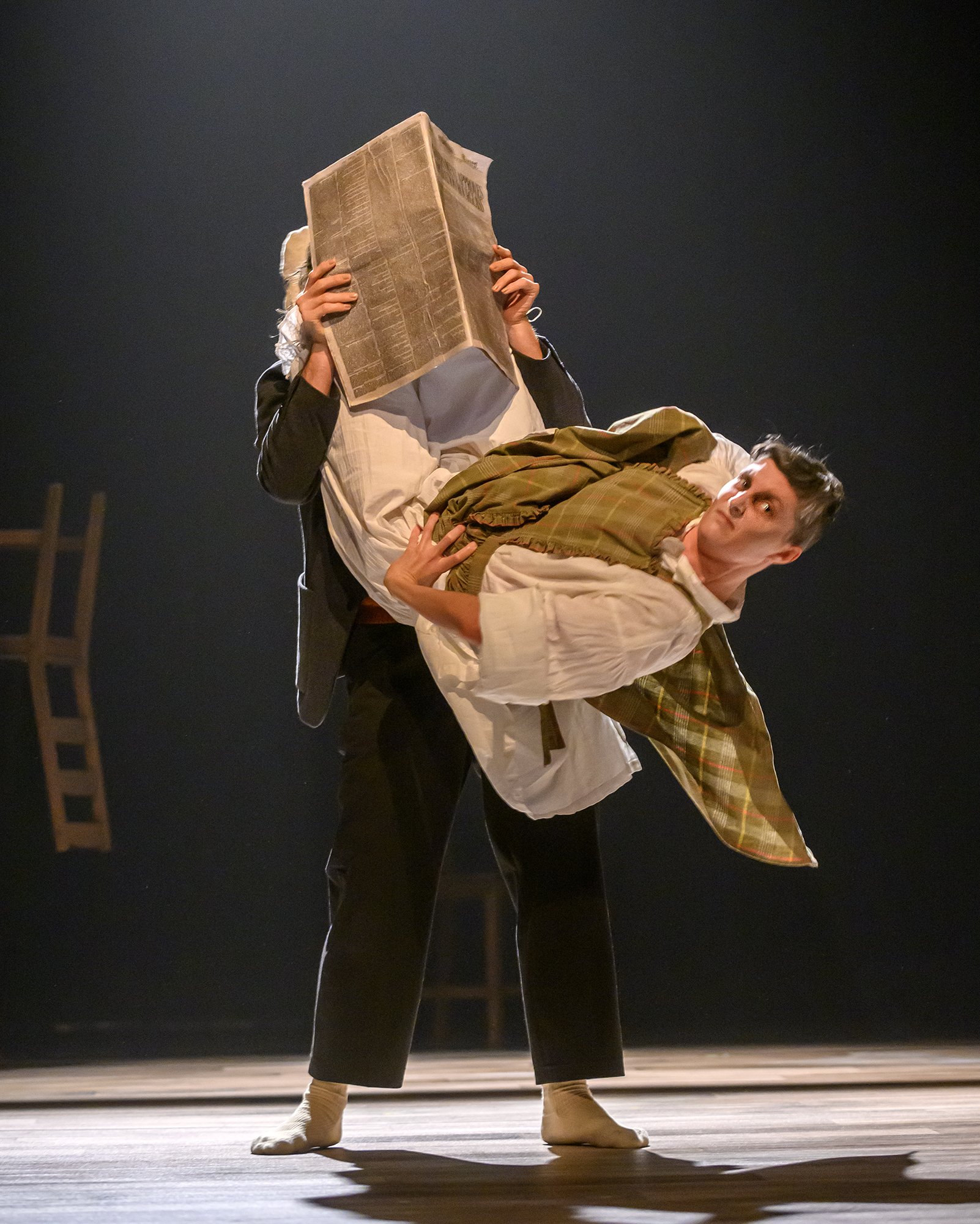

Hourglass. Dancers Kate Franklin and Ted Littlemore. Photo by Chris Randle

At the start of the performance, Jessup pulls objects out of his box, mulling them over—most notably, a miniature wooden chair. It serves as clever foreshadowing that throughout the show, dancers will consistently interact with wooden chairs onstage. This same miniature chair reappears midway through the performance when Jessup’s wife becomes pregnant and gives birth to a baby. But it’s revealed that she’s not holding a baby in her arms—she’s holding the miniature wooden chair.

One of the most striking uses of the chair is when it is wielded by a dancer to begin digging a grave. The chair scrapes along the ground and then is flung over the dancer’s shoulders, imaginary dirt being dropped behind him. The movement is simple, but impactful. The wooden chairs are a stark juxtaposition to the human lives that dance around them; they are constant and never decaying, a strong anchor for the dancers to come back to.

At one point, a fatherly figure is seated on a chair centre-stage, holding a newspaper up to his face, ignoring a woman who dances around him, hoping to gain some attention from her partner—but he doesn’t concede. In dance that seems often to draw on clowning, she even goes as far as wrapping her legs around her husband’s neck, dangling upside down, and swinging from side to side like the ticking of a grandfather clock’s pendulum—yet the man whips the newspaper back up to his face without batting an eye. Though it drew laughs from the audience, the interaction also encapsulates a feeling of lost connection that infiltrates many long-term marriages.

In each scene, the concept of age is addressed captivatingly through the dancers’ movements. In his childhood, Jessup replicates a young boy’s walk by crouching down low and shuffling quickly around the stage on demi-pointe. Many of his movements rebound in resistance, as if to imply that his young self hasn’t quite mastered control over his body yet.

Jessup’s father moves with the weight of age, his walk a shuddering shuffle. Eventually, in a moment of wanting to defy his age, he breaks out into a frenzy of expansive movement and jumps; but the outburst immediately tires him, and his wife helps him stagger shakily offstage.

Though the performance is dripping with dramatic theatrical moments, one thing that remains constant is the dancers’ pure technique. A stellar allegro section mid-show involves a trio of dancers wielding briefcases as they move briskly through a pattern of jumps, taking up space beautifully. Jessup’s character is burdened and distracted by his briefcase, with each step seeming reluctant: he cannot tear himself away from his work, not even to see his child.

Driven throughout by Glass’s repetitively looming, subtly mysterious, and occasionally playful piano notes, the piece comes to a satisfyingly full-circle close when white sheets are once again placed atop the props and dancers. This journey through memories that Hourglass explores captures the trajectory of life; even when it’s unsettling in its open looks at marital distress and aging bodies, it’s breathtaking in its honesty.

While humans don’t get to press rewind and relive a reel of their own lives, getting the chance to watch another’s memories unfold onstage in Hourglass provides the audience with a sense of comfort in knowing they’re not alone—and encourages them to embrace each stage of their life while it lasts.