Five local female artists explore women’s fashion, aerospace, and equality in new North Van Arts exhibition

I wanted to go on a Space Walk but had nothing to wear celebrates achievements of women in science and looks at barriers that have held them back

The Rockettes by Kiku Hawkes.

North Van Arts presents I wanted to go on a space walk but had nothing to wear at CitySpace Community ArtSpace to April 14. A virtual tour is available at northvanarts.ca.

IN MARCH 2019, what would have been a revolutionary mission for aerospace history—the first all-female spacewalk—was cancelled due to an unforeseen issue: There was only one spacesuit that fit both of the astronauts. As a result, one of the female astronauts was replaced by a man, and the date for an all-female spacewalk was postponed.

Frustrated by the news, five female Vancouver artists were inspired to celebrate achievements of women in space and beyond through their work. After a slight delay due to the pandemic, I wanted to go on a Space Walk but had nothing to wear is a group exhibition now running at CitySpace Community ArtSpace in North Vancouver.

The five artists behind the show are Ilze Bebris, Kiku Hawkes, Marcia Pitch, Ruth Scheuing, and Catherine M. Stewart. They display artworks in the form of assemblage, photography, weaving, textiles, printmaking, and media. Through story-telling and rendering of historical events and figures, the artists examine how limitations put on women through fashion have deterred the achievement of gender equality in early and modern society.

When it comes to the show’s title, Stewart says it stems from the fact that each artist tapped into diverse sources for the group exhibition. “We thought it was kind of just a humorous, catchy title that would provide a kind of a core for us to go in different directions and widely interpret in our own way,” Stewart says in an interview with Stir.

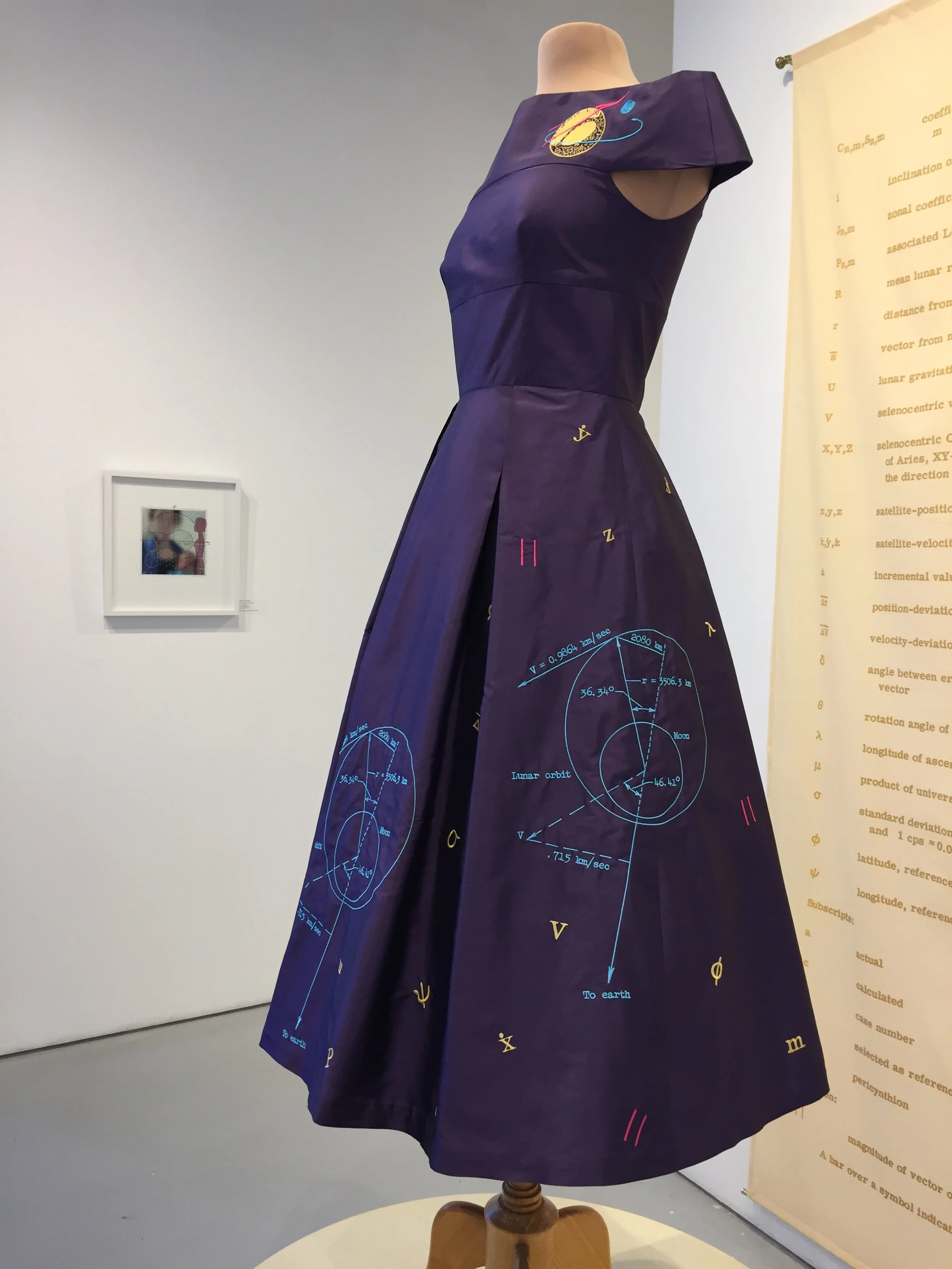

Investigating the intersections between fashion and science, Stewart’s section features Katherine Johnson Dress (2022), a handmade purple taffeta gown as a tribute to the namesake mathematician who made crucial contributions to NASA’s first space mission in 1969. Stewart was inspired by the way Johnson juggled her work as a successful mathematician with that of her role as a mother to two daughters, and her ability to fulfill—and exceed—traditional expectations all while challenging the limitations of being a woman in her field.

“This piece links her professional life as a mathematician with her personal life as a homemaker and an active community member,” Stewart says. “She sewed many of her home clothes, as well as those of her daughters and for members in the community who needed a special outfit to wear to a special occasion. She was very proficient with the sewing machine, so I thought it would be really nice to kind of honour that in her.”

Katherine Johnson Dress (2022), by Catherine M. Stewart.

Embroidered on Stewart’s gown are symbols and diagrams sourced from one of Johnson’s published papers about lunar orbits from 1916. Behind the dress is a backdrop that shows the definition of each symbol, resembling a legend—an explanation of characters, symbols, or markings on a document that might be unfamiliar to the reader, something that Johnson would begin her reports with. “[Johnson] started the paper by showing the symbols that were used in the paper and giving them definitions,” Stewart says. “So I thought, well, I'll use the symbols and then put their definitions which are taken directly from her paper.

Drawing from magazine images of fashion from the 1960s, Johnson’s modest yet elegant style, and insight from local fashion historian Ivan Sayers, Stewart curated a piece that captures Johnson’s brilliance both in her professional and home life.

“[The gown] is one that I thought she might have made herself had she been invited to an imagined NASA event celebrating that first moonwalk in 1969,” Stewart says. “I would like the viewer to consider the connections between the beauty of mathematics, the beauty of a lovely dress, and the beauty of a life fully lived.”

Accompanying Stewart’s handmade gown are nine framed prints featuring Stewart’s own family photos as well as images from a textbook on orbital mechanics, which Stewart believes Johnson used in her work. To emphasize the connection often created between women’s work and home lives, these pieces play up Stewart’s family photos with symbols and diagrams and elements of sewing. “There is a kind of balance where there is not the separation between family and work,” Stewart says. “I’d like viewers to look for a connection between the diagrams and the photos with which they are paired. Who knows—perhaps viewers will be inclined to consider the interactions of their own existential orbital paths with those of the people around them.”

Kiku Hawkes’s The Rockette series takes inspiration in part from garments in the Grimm Brothers’ fairytale of Allerleirauh, wherein the doomed princess has three dresses: one of the sun; one of the moon; and one of the stars. Hawkes presents three digital prints on canvas, each representing one garment from the fairytale. The dancing figure in each print resembles Allerleirauh. Hawkes also takes elements from planet rotations and images provided by NASA and the Hubble telescope as well as Neo-Assyrian copy of a Sumerian clay planisphere documenting the transit of a large asteroid passing over Mesopotamia in 3123 BCE, on its way to decimating a mountaintop in Austria. Hawkes’s series challenges the contemporary view on space exploration by billionaires and “questions if viewing the cosmos solely through a lens of resource extraction and tourism might be using the wrong end of the telescope”, according to her artist statement.

Just before getting ready to mount her work for the exhibition, she added glass globes, which dangle off of each print. Hawkes says each one resembles Morse codes that she rendered from shadows on her wall one particular night. “I went on Google and looked up what the letters might be, and they were E, S—and I kind of thought, ‘Yeah, for women, space travel: easy,’” says Hawkes in an interview with Stir. “These come from a Galileo thermometer. It would be a glass cylinder and the temperature of the environment affects the coloured water.”

Ilze Bebris’s Shameless (2022) uses textiles, driftwood, yarn, and foam earbuds to echo beauty standards enforced on women. Colourful threads and fiber in the shape of breasts and other body parts are assembled in no particular pattern, stringed together in an almost unsettling way. According to Bebris, it represents the “unruly bodies” of women.

“Shameless is a metaphor for the fragmented body, an echo of a culture that sees certain traits as desirable, others as embarrassing or shameful, making women’s bodies sites of exaggerated and commodified desire and endangering women’s health and well-being,” Bebris says in her artist statement.

Detail: Trip Trap by Marcia Pitch from The Invisible Woman (2019-2021).

The Invisible Woman by Pitch revisits the disappointing NASA mission in 2019. In an installation that displays recycled materials and discarded objects from everyday life, such as a used lamp shade, clock, CD, and a denture mold. Pitch’s work is an homage to the discarded and cast-off.

“I am struck by the lack of foresight to tailor for women’s bodies in the world of science and space exploration,” Pitch notes in her artist statement. “This is one of many examples of how women are rendered invisible in a world designed primarily for men. Another inspiration stems from looking closely at what else we cast off. When I picture outer space filled with junk from decades of space travel, I imagine all the useless and archaic relics drifting past. Space will become gold mines for future Archaeologists. What will future generations think of us?”

Scheuing’s section of the exhibition is inspired by the experience of Sarah Henley, a woman who jumped off the 75-metre Clifton Bridge in Bristol, United Kingdom in 1885, saved by her hooped crinoline skirt, which acted as a parachute. Combining her love of old and new technologies, Scheuing depicts Henley’s miraculous story through textile and weaving.

“This story seemed a good entry into space travel with a slightly twisted feminist focus,” Scheuing says in her artist’s statement. “I later explored the early lighter-than-air ballooning craze and its aeronauts. One of the first women aeronauts was the French Sophie Blanchard (1778-1819), who made over 60 solo flights after the death of her husband and ballooning pioneer Jean-Pierre.”

Through the exploration of humour, fashion, art, space, and breaking boundaries, the five artists behind I wanted to go on a Space Walk but I had nothing to wear shine light on the modern and historical constraints of women — not only in aerospace, but in all facets of life.

For more information, see North Van Arts.