IzumonookunI pays contemporary tribute to forgotten female founder of kabuki, at the Powell Street Festival

Aretha Aoki’s interdisciplinary dance work draws on everything from synthwave to taiko and Ziggy Stardust

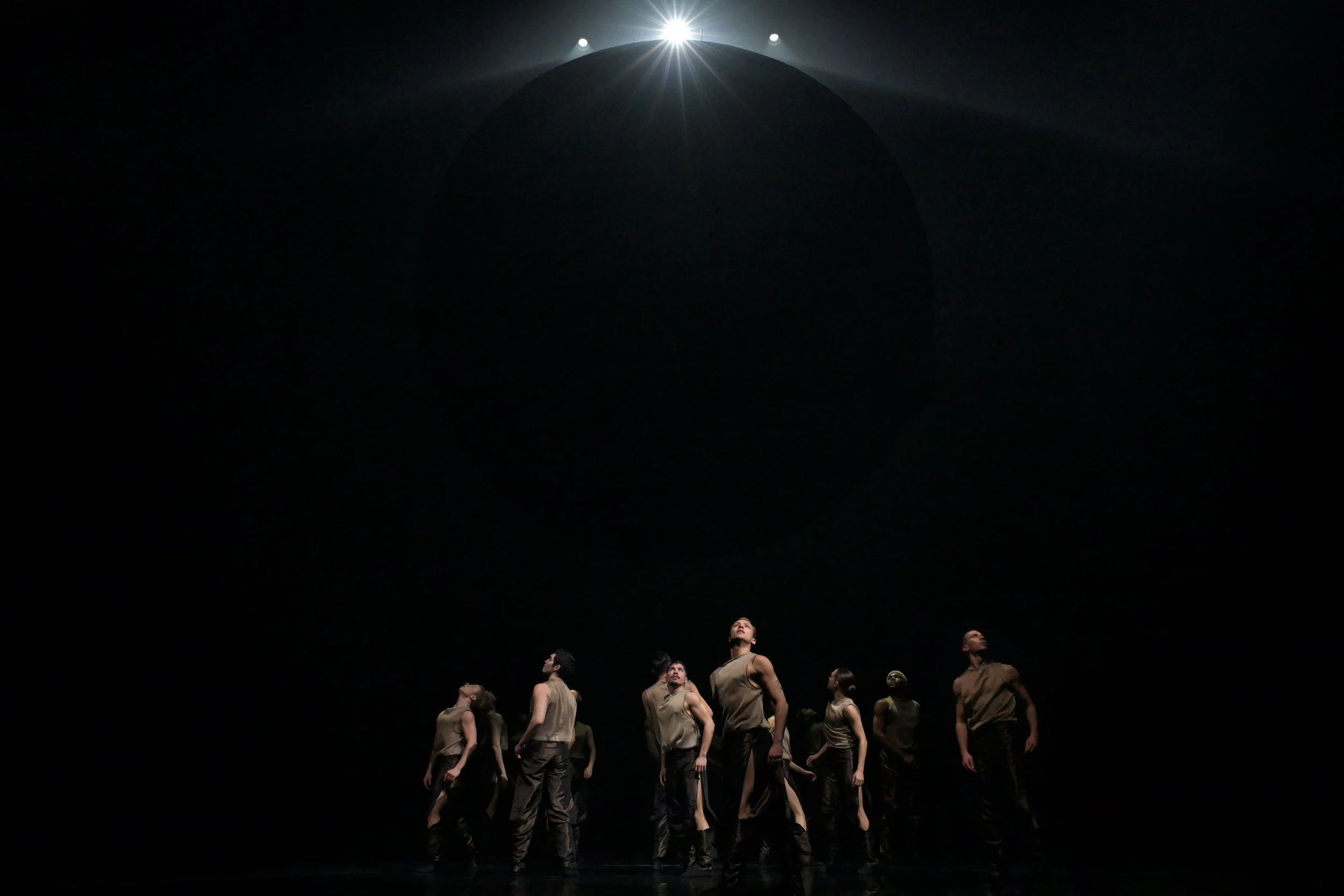

Photo by nikki lee

Powell Street Festival presents IzumonookunI on August 5 from 3:15 to 3:45 on the Diamond Stage in Oppenheimer Park. The fest runs August 5 and 6, 11:30 am to 7 pm in and around the park

FOR CENTURIES, THE iconic Japanese art form of kabuki has been associated with male-only performers—a holdover from an early-1600s decree banning women from the stylized dance-theatre form.

But what many don’t realize is that it was a woman, Izumo no Okuni, who invented kabuki. The shrine maiden started performing the song-filled dramas with a group of lower-class women—many of them sex workers—in the dry riverbed of Kyoto’s Kamo River. The art form was an instant hit that would go on to last centuries, although few details are known about Okuni, who disappeared into the fog of history around 1610.

Vancouver-raised, Maine-based contemporary dance artist Aretha Aoki became fascinated with Okuni’s story when she stumbled upon it in a documentary about kabuki a few years back. The result, premiering at the Powell Street Festival this weekend, is a multidisciplinary new dance work named IzumonookunI that she brings home to the Powell Street Festival this weekend.

“She’s become this inspiration,” Aoki says. “She was kind of this outsider….We don’t know when she died; she disappears soon after women are banned from kabuki. It’s the mystery and the erasure and the surprise that there is this major form—one that this is a national treasure in Japan—and we don’t know the story of her.

“And sadly that erasure is not that uncommon for a lot of women who do important things,” the dance artist and teacher continues. “She is groundbreaking in 17th-century Japan—she’s an entrepreneur in a way, and she’s getting together these outcasts and prostitutes, and going ‘There’s this other way to make money through art.’”

Fuelled by the all-female drumming group Sawagi Taiko, synthwave electonic music, and costuming and makeup that’s as much Ziggy Stardust and Siouxsie Sioux as traditional Japanese performance, this is not a strict biographical portrayal. Neither is it traditional kabuki.

Instead, Aoki and her partner in life and art, Ryan MacDonald, use the classical Japanese art form as a springboard for theatrically charged ideas about ancestral heritage, personal history, empowerment, and reclamation. The heroine becomes a kind of wild, goth-glam-punk fury, moving to MacDonald’s live, looping electronic score and the thundering drums of the five female taiko percussionists (Sawagi members Linda Uyehara Hoffman, Kathy Shimizu, Anny Lin, Felice Kwo, and Fin).

Festival-goers will recognize such touchstones from kabuki as white face paint, outsized expressive facial expressions, vocalizations, and a kimono—albeit a glam, sparkly sequinned one. “We’re interested in blurring the contemporary and traditional in terms of sound and movement,” Aoki explains.

Perhaps the biggest inspiration from the classical art form comes from a translation for the word kabuki itself: “One definition is ‘strange’ or ‘indecent’,” Aoki says.

Look for the pair’s six-year-old child, Frankie, in the work, too—often on a nylon swing that brings an added sense of play to the staging. Aoki enjoys the way the show erases boundaries, not only between art forms but between generations, and past, present, and future.

As for the artist herself, she loves the idea that the work is being performed outdoors at Powell Street Festival in Oppenheimer Park—a bit like those open-air riverbed performances by kabuki’s female founder. For the SFU fine-arts grad who has been away from Vancouver since the mid 2000s, pursuing her MFA in the U.S. and now an assistant professor of dance at Maine’s Bowdoin College, the festival feels like a homecoming. “I went a little bit as a kid, but as a young artist, Powell Street was my first professional gig,” reflects the dancer, who will premiere the full-length ode to Okuni south of the border next year. “It’s where my first art and activist community was, and it really shaped my identity."

IzumonookunI