Jeremy Dutcher returns to West Coast, finding new ways to express himself in songs from his sophomore album

Appearing at the Vancouver Folk Music Festival, the celebrated two-spirit Wolastoqiyik artist explores land rights, injustice, and more from powerful Motewolonuwok

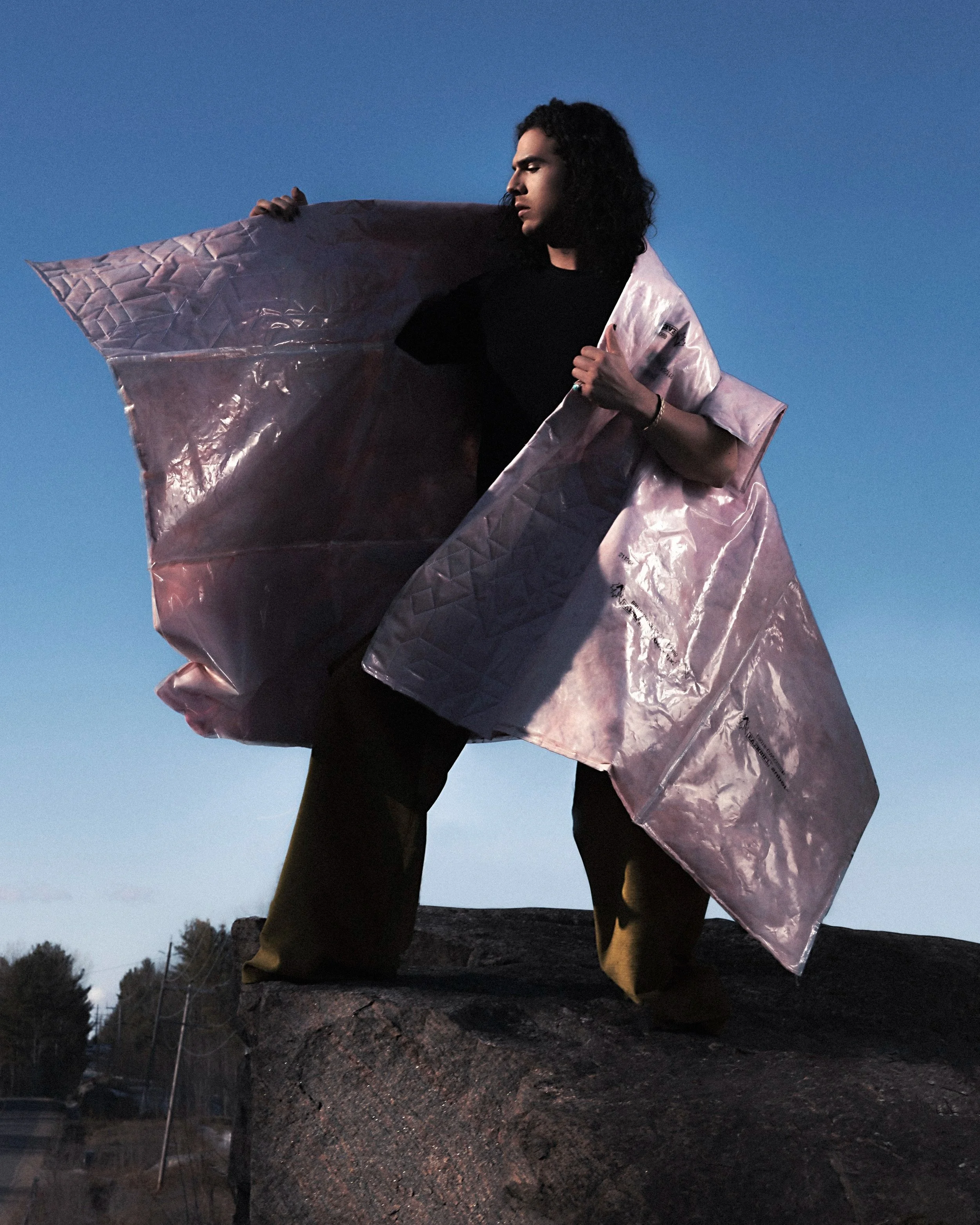

Jeremy Dutcher. Photo by Kirk Lisaj

Vancouver Folk Music Festival presents Jeremy Dutcher on the Main Stage on July 21

JEREMY DUTCHER HAS BEEN on a ride he never saw coming since the 2018 debut of his Wolastoqiyik Lintuwakonawa, an album featuring new songs based on Wolastoqey-language originals from early-20th-century wax-cylinder recordings. The operatically trained member of New Brunswick’s Tobique First Nation created the album for his own community, but its luminous music spoke to a much wider audience. It ended up catapulting him to Polaris and JUNO wins, performances for NPR’S Tiny Desk Concerts, features in Vogue, collaborations with Yo-Yo Ma, and concerts in cities from New York City to Paris.

Almost six years later, the West Coast will hear a slightly different Dutcher as he hits the Vancouver Folk Music Festival, riding high on his sophomore album Motewolonuwok, where the songs are alternately moving and powerful. In the spirit of “Take My Hand”, a track backed by a crescendoing chorus, swishing drums, round-midnight horns, and rousing heya, heyos, he invites a broader public to explore the experience of contemporary Indigeneity with him. “Take my hand and walk with me,” sings the two-spirit artist.

Notably, Dutcher sings not just in his gorgeous, flowing mother tongue but, for the first time on an album, in English—an act of reaching out that hand to his growing legions of fans. But when he first sat down to create Motewolonuwok, he was not without his doubts; when you’ve worked tirelessly to keep a language alive that only 100 or so people still speak fluently, it’s hard not to feel like you’re abandoning the cause.

“I was super reticent,” begins the authentically affable Montreal-based artist, who’s happy to be spending downtime on his home territory in the Maritimes when Stir reaches him. “I wasn't ready, I think, at the start to go into that English journey. Because for me, the whole reason why I started sharing my music was about cultural resurgence and revitalization—not just pointing towards our historical song tradition, but also our language and the messages and philosophies that are found in our songs.”

He continues: “For me, it always came back to ‘You’re doing it because when you grew up, you didn't have a school where you could go and learn your language.’”

But Dutcher came around to the idea of being able to share those messages and philosophies wider through English. And he felt secure that his first album had formed the foundation for his work in Wolastoqey. “As we always say, ‘Well, we gotta do it our way first,’” he says. “That’s how we introduce ourselves and how we start our gatherings around here: it’s always rooted in the language.”

Motewolonuwok expands on the sound of the first album—tracks like “Sakom” feature a rising 12-voice choir made up of Dutcher’s queer and allied kin, with orchestral swells adding to the beauty of the musician’s grand-piano playing.

It feels natural to compose at the piano, Dutcher says. “I carry with me this sort of imposter syndrome, because I’m a self-taught pianist,” confides the artist. “I never took a lesson, I don't know if it’s very technically correct, but I enjoy it. I just play what sounds nice to me.”

While much of his 2023 album draws on lush orchestral and choral textures, Dutcher will strip things down a bit at the Folk Fest here, accompanied by an ensemble with upright bass, guitar, trumpet, and drums. “They play fluidly and move in unexpected ways, because jazz kind of moves that way,” says the artist who feels a deep affinity for the West Coast. “So, yeah, I love working with really flexible musicians, and I have this amazing group of people that I've been working with over this last year or so.”

Dutcher explores sociopolitical issues and sometimes emotionally wracking territory in his deeply empathetic new songs. Powered by resonant strings, “Skicinuwihkuk” creates a stunningly moving ode to land protection. The jazz-inflected “Ancestors Too Young” tackles the epidemic of suicide amid Indigenous youth. And the aching “The Land That Held Them” touches on the tragedies of Tina Fontaine and Colten Boushie (“Into the water she wade/Propelled by the air he lept”).

Dutcher reveals that he actually ended up dialling back the emotion in that last song to let the facts speak for themselves.

“Because the whole song was kind of thinking about the casualness with which we treat Indigenous life as each of us is looking at all of these stories that we've heard in the news,” he relates. “And so I sat there and did it with just the coldness and the detached nature of that. Kind of paradoxically, when you want to offer something highly emotional, taking yourself out of it and just offering the details of it can be more effective than trying to put yourself in it too much.

“I wrote this song because I was kind of pissed off,” Dutcher adds. “You know, why are these just headlines? Why can't we actually honour these people's stories? This is just one particular instance, but there are many kinds of decisions around when to share, how vulnerable to be, does it feel good, how to tell a story. I guess this is why it takes me five years to make an album!”

Speaking out, whether it’s for land sovereignty, queer rights, injustice, or language protection, has always come easily to Dutcher.

“I've been fortunate in my life to be allowed to express myself in ways that feel good and free to me,” the singer says. “I’ve had very supportive parents and community and family around me. So in a way, it's like breathing, you know, just to express and tell your story.”

Jeremy Dutcher. Photo by Kirk Lisaj

That expressive force will be on full view at the Folk Fest, as will the famous stage presence of an artist known for his flowing and sometimes intricately braided long hair, showstopping Indigenous-designed outfits, and beaded regalia.

At the concert here, what may prove to have evolved most perceptibly is his voice. The radiant, arresting tenor of Wolastoqiyik Lintuwakonawa has taken on complex new colours—in some ways freeing itself further from operatic training. At times Dutcher finds a quivering fragility on Motewolonuwok that reminds you of Anohni. At others, he taps a powwow fire—his technique and vocal power clearly honed.

“From the get-go, what I really tried to think about was honouring all the ways of making sound with your voice,” he says. “I was very fortunate to grow up around song keepers in the lodge. All music has a pedigree, is what I'm trying to say. All music has a lineage. And even though we might think of them as very different—traditional music and operatic music—they both need the same breath. They're both rooted within the body to make that noise.

“I’ve been trying to weave together these two seemingly very separate aesthetics and ways of making music. And I keep coming back to this term: ‘the middle voice’. I was always looking for the middle voice, which is to say, What is the balanced place between these two seemingly polar opposite ways of making sound?”

So much of what Dutcher does so beautifully is bridge worlds together, to offer his hand at a time when people and cultures seem divided. That he can find the middle ground through his mesmerizing music perhaps gives hope that the rest of us can find common ground as well.

“My mother is Wolastoq and my father is a settler, and seeing them find each other, and love each other, and disagree, and come to understanding—I think it sent me on a path to think that that was possible,” the artist reflects. “Whereas I think a lot of people in this moment right now don't know that that's possible—that we can actually talk across those lines.

“I'm here to tell you from inside the house, it is possible,” adds Dutcher. “It requires work and deep listening—which is why music is great too, because it kind of inculcates us to do that.” ![]()