Vancouver Opera leaps into new digital realm with La Voix Humaine's intensely emotional ride

Vancouver-bred star Mireille Lebel takes the punishing lead in a production that aims to bring the stage to your living room

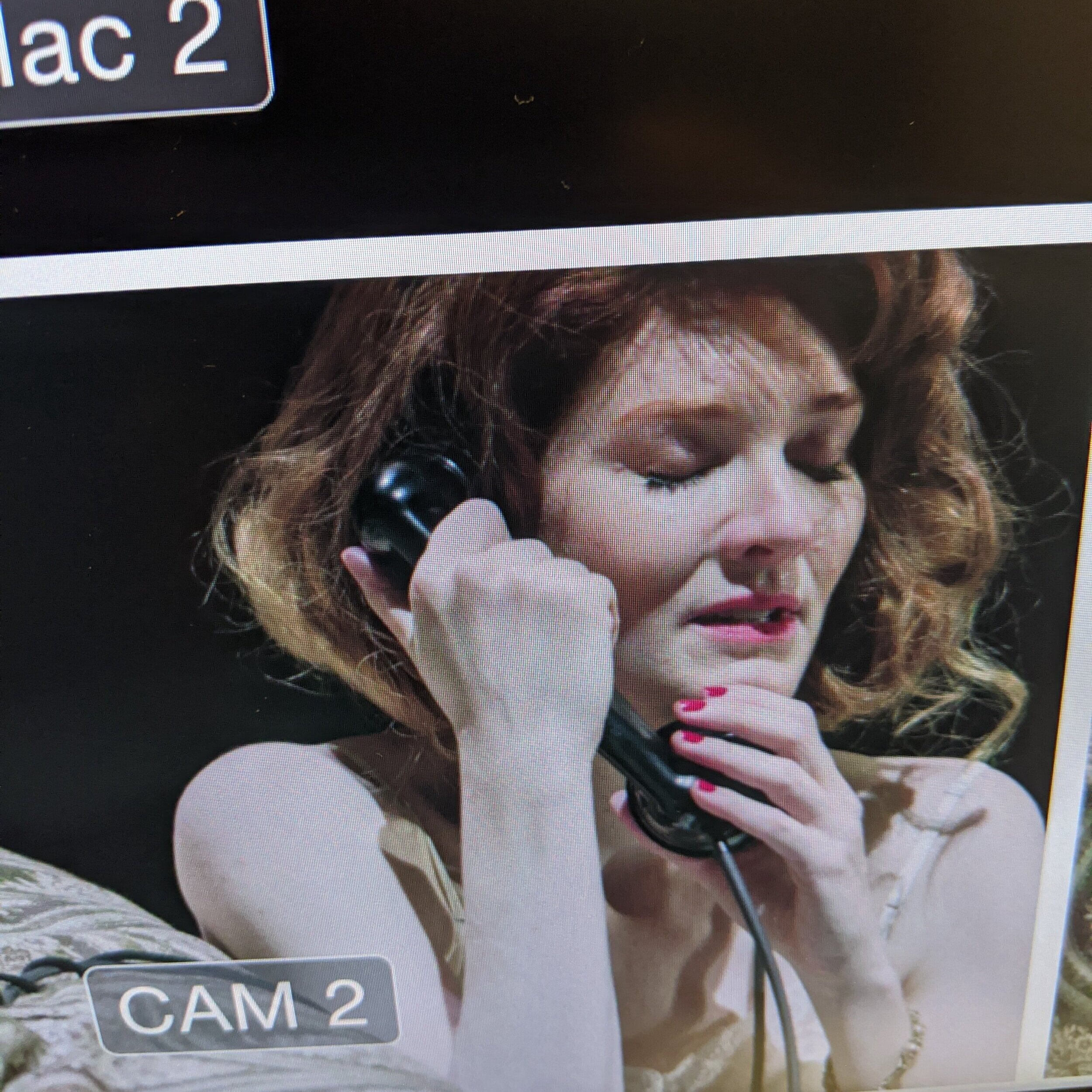

Lebel on camera in La Voix Humaine. Photo by Caitlin Fysh

Mireille Lebel. Photo by Pierre-Etienne Bergeron

Vancouver Opera streams La Voix Humaine starting October 24

AT FIRST GLANCE, the performance taking place on the Chan Centre stage is like any other immersive opera experience.

Looking like a 1940s femme fatale, auburn-haired, Vancouver-bred mezzo-soprano Mireille Lebel wears a slinky slip, moving across a vintage-chic set with a tufted couch, beauty table, clawfoot tub, and unmade bed. In Francis Poulenc’s 20th-century solo opera La Voix Humaine, she sings entirely into a phone--in this case carrying around an old-school black version--unleashing emotion on her ex-lover and herself. “Tout est ma faute!” “Je suis stupide!”

But Lebel, now a draw in opera houses from Berlin to Naples, is not singing to a packed audience. Except for a lucky handful of people invited to see her perform, the rows sit empty. Instead, seven cameras point their attention on Lebel. Her accompaniment comes not from an orchestra, but from music director Kinza Tyrrell, at a grand piano off to the side on the stage. And at the end of the scene, a voice suddenly yells “Cut!”.

This is an inside peek at what the coming opera season is going to look like in the pandemic.

The most expensive art form, opera faces some of the biggest challenges during distancing measures. The VO is used to operating on a grand scale; now it’s moved to digital programming it hopes will retain the high production values its audiences are used to, albeit with works that have drastically reduced casts and musical accompaniment.

“I want to get the orchestra involved so bad. That’s the hard part,” the VO general director Tom Wright tells Stir a few days after the in-person preview. “I can’t involve the whole opera family right now.”

Still, on the day Stir catches up with him, he’s pumped about the first edit of the La Voix Humaine he’s seen and the stage production values it’s captured.

Rachel Peake, Mireille Lebel, and Kinza Tyrrell make up the all-female leadership team on the filmed stage production of La Voix Humaine.

“The film noir-esque lighting and setting were the first things I noticed, and I thought, ‘Yup! You’ve nailed it!’” he says.

When COVID first set in last spring, the opera took the lead of bigger institutions abroad with the idea of going digital. But while major companies like New York’s Met could dig into years of filmed works to broadcast to the masses, the smaller VO had no such resources.

And so, it set about filming some new, more intimately scaled works. Wright says the first challenge was where it could stage a production, and the Chan was the only option, with civic theatres closed. (No announcement has been made yet about when the VO’s regular home, the Queen Elizabeth Theatre, might reopen.) Early in the pandemic, the Chan had invested in additional production crew and state-of-the-art production equipment and cameras.

Wright heard that Lebel was interested in taking on Poulenc’s challenging work, and so the VO assembled an all-female team, with Tyrrell for music direction and Rachel Peake, who helmed La Cenerentola and The Marriage of Figaro here, to direct.

Wright says the one-singer, one-act work, in which the woman (“Elle”) expresses anguish, loneliness, and depression to her former lover, seems custom-made to the themes of these lockdown times. Poulenc based his 1958 opera on Jean Cocteau’s play of the same name.

“The opera and the play are about isolation, about being alone, and that speaks to what people have gone through in last seven or eight months--both some people forcibly being alone and some people being alone with their loved ones for longer than they intended,” Wright says.

In the work, the main character Elle and the former lover on the other end of the phone repeatedly get cut off during their call. The one-sided conversation we hear travels from soft pleading and angry outbursts to beautifully sung revelations and dark confessions. Tyrrell’s piano playing can be lush and cascading or angular and harsh. It’s an intense, melodramatic ride, and a feat for the singer, who has to pour everything she’s got into it.

VO general director Tom Wright

The digital season continues with much different fare: next up is what Wright describes as perhaps the “biggest” streamed production, Amahl and the Night Visitors (premiering December 12). Commissioned as a holiday special for NBC TV in 1951, the family show will star conductor Leslie Dala’s 14-year-old son Andreas with a socially distanced cast. The elder Dala, music director for the production, also will accompany the performance with VO répétiteur Tina Chang in a reduction for two pianos.

In the spring, watch for Richard Wargo’s one-act comedy The Music Shop and La Tragedie de Carmen, Peter Brook and Marius Constant’s stripped-down reimagining of Georges Bizet’s classic; just what form they’ll take may depend on which theatres are open, and what kind of pandemic measures are still in place.

All will be available to stream at-home for a $99 subscription from the VO’s own platform, which the company has also been building.

“A hundred dollars to watch four operas produced at high production values--that’s a great deal because you can bring your family members under one roof and enjoy a wonderful production,” says Wright. “Normally it’s around that to see just one of our [live] shows.”

Wright also hopes to add streamed recitals to the mix to keep opera alive this season, even if it doesn’t look like quite the auditorium-filling extravaganza it normally does.

“And if we do it well then, yes, we should be able to make this as an alternative revenue stream,” he says. “If we build this audience who’s interested in what we do and they watch from afar then there’s no reason we shouldn’t.”