Matriarchs Uprising taps a growing wave of Indigenous women innovating in contemporary dance

A full roster of new video works streams all week, while a live double bill features choreographer Jeanette Kotowich’s exploration of sovereignty and Cree cosmology

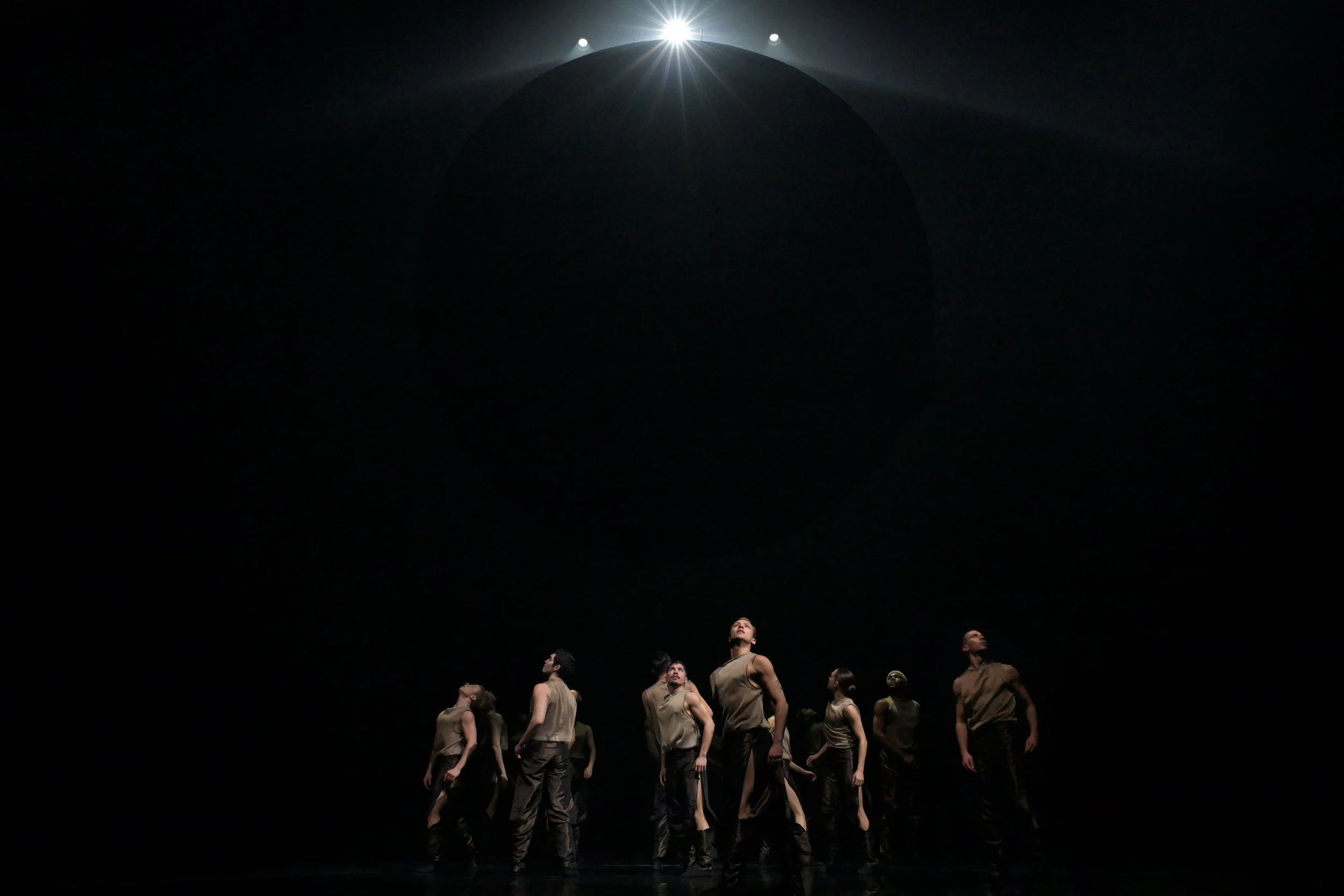

KWE features Tamar Tabori, Olivia Shaffer, and Stéphanie Cyr. Photo by Yasu Okada.

Maura García. Photo by Gosdayi.

O.Dela Arts and the Dance Centre present Matriarchs Uprising live and online from February 14 to 19

LESS THAN A YEAR before the pandemic shut down the performing-arts world, Vancouver dance artist Olivia C. Davies pulled off the almost-impossible: she staged a three-day event celebrating Indigenous women in contemporary dance. Matriarchs Uprising, the culmination of her residency at the Dance Centre in 2019 and a longtime dream, brought visitors from as far away as Australia for performances, events, and circle discussions.

Three years later, Matriarchs Uprising is staging another installment, combining live performances, an array of new video pieces, and online discussions—and it’s growing, despite the state of the world.

“It’s amazing and the dream is very much alive and well—it was a one-woman operation in 2019,” Davies reflects to Stir, pointing out she now has a dedicated festival coordinator (general manager Brian Postalian) and a marketing manager (Kelly McInnes).

It’s rare for any festival to get off the ground, let alone flourish during the pandemic. But the success of Matriarchs Uprising speaks not only to Davies’s abilities and dedication but to a surging group of Indigenous women, here and elsewhere, who are innovating in both contemporary dance and their own cultural forms—and decolonizing the stage and the wider world in the process.

“I feel it’s exploded,” Davies says. “I see that more and more in spaces around not only Vancouver and across BC and the country, but worldwide. It’s exciting and it’s got a beat of its own.”

This year’s festival features not just live performances (which were sold out at last check) but an on-demand video program that showcases the wide range of emerging voices in the field of contemporary Indigenous dance. Amid the online offerings: Christine Friday’s Firewater Thunderbird Rising, touching on ancestors, dreams, blood memory, and the land directly connected to her Anishinaabek ways; Nipissing artist Animikiikwe Couchie-Waukey and Maori artist Bella Waru’s Within the Layers, an exploration of ancestry and identity, with acclaimed choreographer Penny Couchie lending a hand as dramaturg; Métis-Assiniboine artist Sandra Lamouche’s Gather, inspired by the Soniyaw niyipsi berries whose seeds are made into necklaces for spiritual protection; and Ktunaxa dancer Samantha Sutherland’s ȼ̓inaⱡ upxamik, in which the artist expresses the importance of her Indigenous heritage in her life.

Sutherland’s piece is an example of the way Matriarchs Uprising has made an impact on a new generation of dance artists in just a few short years. “Samantha was a young dancer who came up to me after witnessing the 2019 performances and said, ‘I really want to explore my own Indigenous roots, and I hadn’t thought of it too much before coming here,’” says Davies, who serves as a co-mentor on the piece, “and now here we are in 2022 and her first solo work is a re-remembering of her Indigenous roots.”

Sandra Lamouche. Photo by Leland Chapin

The live performances on February 18 and 19 at the Scotiabank Dance Centre feature a double bill of KWE, by Vancouver choreographer Jeanette Kotowich, and Ancestor Dances by American artist Maura Garcia (of non-enrolled Cherokee-Mattamuskeet heritage), whose work is inspired by the stories and movements of seven of her recently deceased ancestors.

As for Kotowich, who is of Nêhiyaw Métis and mixed settler ancestry, her KWE is an ensemble work that explores Nêhiyaw (Cree) cosmology. The word Kwê derives from iskwêw (feminine spirit) and iskotêw (fire). Kotowich describes it to Stir as an act of courage, one in which bodies seek sovereignty, pushing back against colonial and patriarchal structures through movement.

The choreographer, whom dance fans have seen perform for Raven Spirit Dance, says the idea of sovereignty was inspired not just by movements within her own culture, such as land-back protests, but also wider initiatives like Black Lives Matter.

“What I started to realize is no one’s going to give you agency; no one’s going to give you sovereignty,” she says, “you have to take it back.

“In this case the audience is actually being invited to witness this person’s empowerment rather than consuming that person’s empowerment,” Kotowich adds.

The fluid KWE, which draws on everything from sky imagery to the electric energy at music festivals, is performed by a non-Indigenous cast—Stéphanie Cyr, Olivia Shaffer, and Tamar Zehava Tabori.

“It’s been a really beautiful experience, because we have had many deep conversations around ‘What does it mean to be engaging with my world view—as I say, my cosmology?’” Kotowich says. “It’s such a sensitive sharing of things. First and foremost, we’re all human so we share that same understanding when we talk about sovereignty or patriarchy, we hold that as a group.

“I feel like my body is a giant hug around the work,” she continues, “so it has this Indigenous framework around it but then, for the people working the material, it’s not even essential that they’re Indigenous, because their body is so connected to my body. They never feel like I’m asking them to perform my culture. They don’t ever feel like they’re mimicking my movement.”

Like so many other diverse pieces on the Matriarchs Uprising program, Kotowich’s work is bridging cultures and art forms, even as it’s being shared in the supportive space of the festival.

In guiding Matriarchs Uprising, Davies keeps coming back to the notion of the circle, a key symbol in Indigenous spirituality, family structure, gatherings, songs, and dances. As she puts it: “Right now as a whole circle of humanity we’re trying to find ways to gather hope and to find the care we need to move on and to move out of the decaying structures crumbling all around us and really find a way forward.”