Never Twenty One pushes beyond gun violence into Black identity and creativity

Presented by the PuSh fest and Dance Centre, Smaïl Kanouté’s intense dance work draws on his own quest to connect with Afro communities around the world

The Dance Centre and the PuSh International Performing Arts Festival present Never Twenty One at the Scotiabank Dance Centre from January 19 to 21

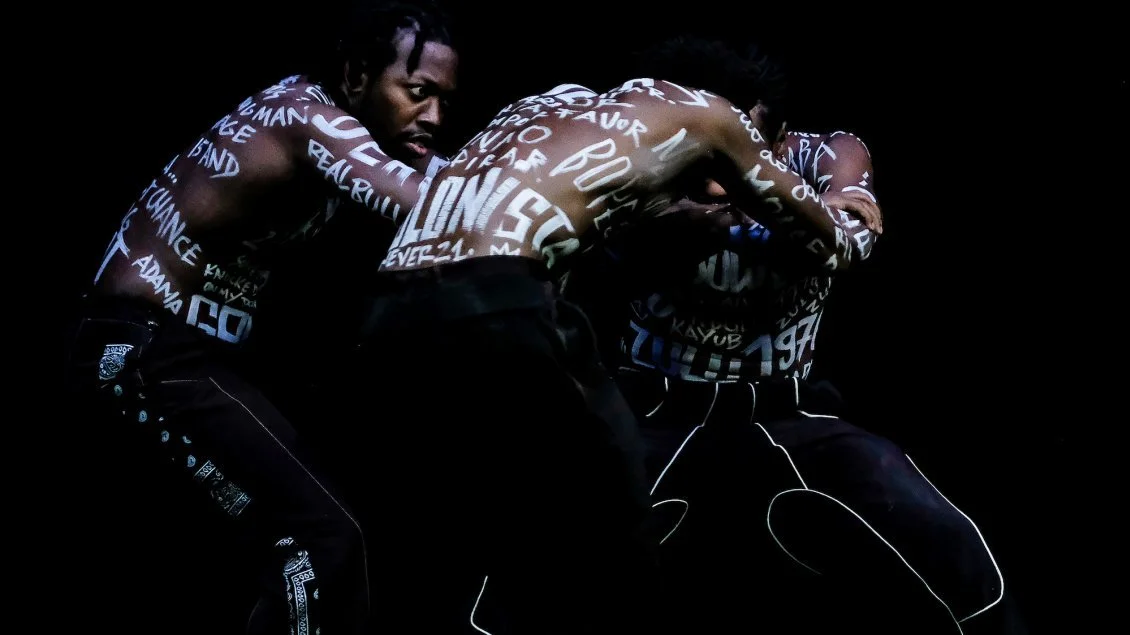

FRENCH-MALIAN DANCE ARTIST Smaïl Kanouté’s riveting Never Twenty One is riddled with disturbing imagery that’s all too familiar: Black men kneeling with their hands behind their head, being caught in the glare of flashlights in the dark, and jerking to the sounds of bullet fire.

Named after Black Lives Matter’s #Never21 hashtag, the dance performance refers to the shootings that have cut young lives short.

But over a Zoom interview from the Paris banlieue he calls home, an impassioned Kanouté explains that his intense work—featuring three Black dancers with words graffitied across their bare torsos—is less about gun violence than potential, resilience, and creativity.

“Yes, we live in an atmosphere of gun violence, but within that atmosphere you have young people who create the greatest music and dance in the world,” the Compagnie Vivons! artistic director begins. “Because when you live in a dangerous city or environment, you don't know if tomorrow you will still be alive. And so each day you create your own identity, your own music, your own dance.

“This is why hip-hop culture is getting stronger and stronger, day by day, because you have this emergency of the creation, you have to create your own place, your own identity, because society will not give you this place,” he continues. “You have to take this place. Each day is like a battle, like a strategy to say to society, ‘We are here and we have to take our place and create our own language.’ In this piece, I want to talk about this good energy.”

Kanouté devotes his life to travelling the world and spending time with the Afro communities he meets there. And it’s in Rio’s favelas, in Johannesburg’s townships, and in the Bronx’s streets—all places that have specifically inspired this show—that he says he has found the most creativity amid youth.

Dance styles from all of those urban communities meld and morph into Never Twenty One’s physically charged choreography. The hybrid movement spans krump, popping, passinho, and baile funk, with contemporary dance.

The trio of performers move to the sounds of a pulsing electro soundtrack and the voices of testimonials from shooting-victims’ family members. (The result is breathtaking: check out the trailer below.)

The words that emblazon the dancers’ bodies are drawn from the latest news reports of gun violence in whichever city the troupe is visiting at the time.

“For example, we went to Mexico in November, one day after the shooting of 12 people by a gang,” Kanouté recalls. “We woke up and we saw the news and we decided to pay tribute to those 12 victims. On stage our dance was even more strong, more real.”

Kanouté admits that Never Twenty One is an incredibly intense piece to perform. He describes the dancers as having to “bridge the visible and invisible worlds”: they’re connecting to the spoken testimony, and the young people lost to gun violence. In some moments, the artist sees Never Twenty One as a lament; in others, it’s like a ceremony.

“There are also a lot of messages, and you have to defend the piece,” he adds. “At the same time, it is our own story–because we are affected by the subject. We live it.”

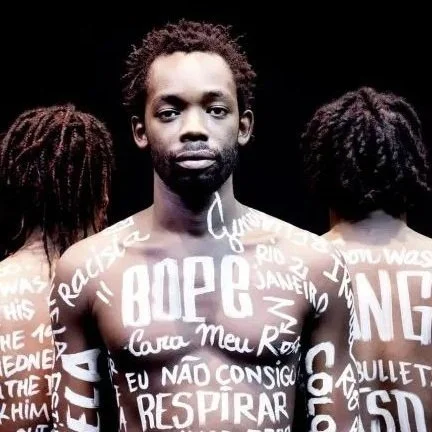

Beyond that intense content, the work has a striking look—and it comes as no surprise that Kanouté splits his time as a respected graphic artist. (He graduated from the National School of Decorative Arts in Paris, and his accomplishments include screen-print collections through the WEAR'T collective, training with Brazilian artist DEUG, a collaboration with stylist Xuly Bët for New York Fashion Week 2016, customized designs for Doc Martens’ DIY Doc’s, and limited-edition totes and tees for AFROPUNK.)

“When I create a choreography, I create it like a painting,” he explains. “The first step is always images.”

Smaïl Kanouté. Photo by Renaud Monfourny

But the biggest inspirations for Kanouté are the constant connections and research he makes on his trips around the world.

Those journeys are part of a quest that, he says, began when he was a young adult.

“I want to meet the Afro community for continued research about the results of slavery business,” he says. “And also the goal is that we have to know who we are. In my case, my parents come from Mali in West Africa and I am a result of the colonization of West Africa.

“So I go back to Africa to know the story of my country and the empire and Mali and the story of Africa. I want to continue to meet people and reconnect to these origins that were cut by the slavery business and colonization.”

Kanouté reveals he’s never felt at home in France or Mali: in the former, he’s seen as an African; in the latter, as a Frenchman, he says.

“I didn't have a specific country, so I decided to create my own identity and my own country with different travels,” he explains. “And now I feel like I’m French, Brazilian, Malian, Senagalese….I created a connection with the people and stories that touched me.”

He adds: “My work is a kind of Afrofuturism–but for me it's not just for the Afro community but for everybody who doesn't know their origin. It's a process I want to share.”