Isabel Vincent shares story of opera-loving British sisters who saved Jewish musicians from the Nazis at JCC Jewish Book Festival

Author of Overture of Hope put her investigative-journalism skills to work in researching the women’s overlooked history

The Cherie Smith JCC Jewish Book Festival (February 11 to 16) presents Opera in Times of War: Isabel Vincent, the closing event, on February 16 at 8 pm at the Jewish Community Centre. Vincent will appear alongside City Opera Vancouver’s soprano Catherine Thornsley with Roger Parton on piano, who will perform arias by Giacomo Puccini and Richard Strauss.

In 2017, when New York Post investigative reporter Isabel Vincent first learned about a duo of self-described British spinsters who had quietly ferried more than two dozen Jewish musicians, conductors, opera singers, and others out of Austria and Germany during the Third Reich, she was intrigued.

A friend who’d visited The Garden of the Righteous Among the Nations in Jerusalem told her about a pair of trees planted there in honour of sisters Ida and Louise Cook. “I looked them up and realized there's very little out there about these women,” relates Vincent, a former Globe and Mail reporter and Torontonian, on the line from New York. “They were given the distinction by Israel of Righteous Among the Nations in 1965, at the same time as Raoul Wallenberg and Oskar Schindler. And you’ve never heard of Ida and Louise, but you’ve heard of Schindler and Wallenberg. Is it because they were women that they fell through history?”

Vincent was determined that the Cooks would be the subject of her next book, although her publisher was less enthusiastic. “They were like, ‘We don't know how you're gonna do that, because Louise Cook burned the archives about the people they'd saved,’” she says. But with her reporter senses tingling, she wasn’t ready to let the Cook sisters fade into the mists of time. “I sort of looked at them and said, ‘Well, you can always figure stuff out. You can always find a different way. There's always a back door.’”

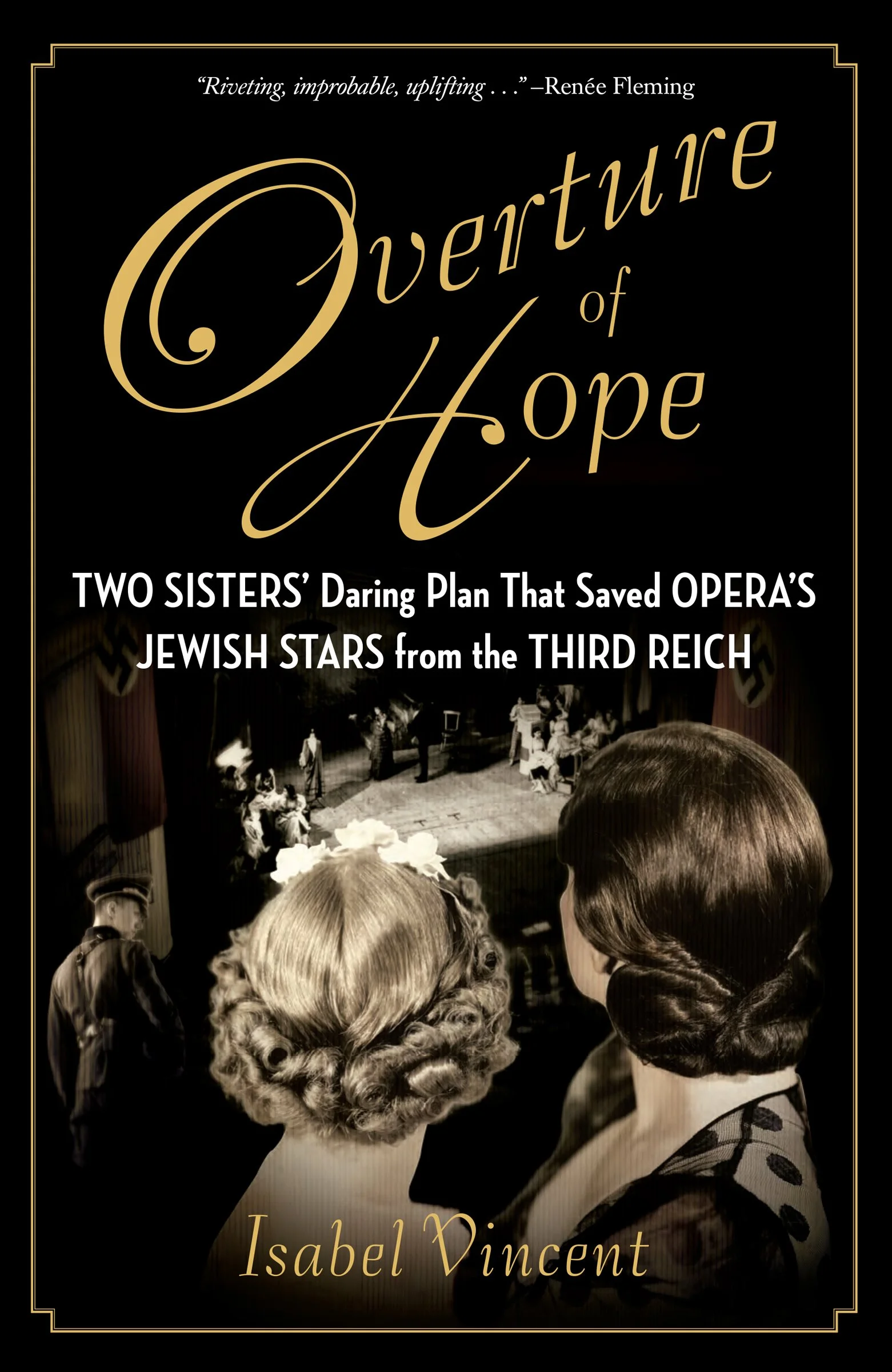

Vincent found that back door in the archives of the opera stars the Cooks had befriended and corresponded with throughout their lives. Her research led to Overture of Hope: Two Sisters’ Daring Plan that Saved Opera’s Jewish Stars from the Third Reich (Regnery History).

Unmarried, middle-aged, and employed as typists with the civil service, the Cook sisters found their romance and passion in opera. Unabashed groupies, they would spend hours camping outside London’s Royal Albert Hall and Covent Garden for tickets, sending fan mail to their favourite singers and conductors, such as Italian soprano Amelita Galli-Curci, which lead to some genuine friendships. The most consequential of these was their relationship with Austrian conductor Clemens Krauss and his wife, Romanian soprano Viorica Ursuleac.

The sisters travelled regularly to Salzburg and Vienna to see performances by Ursuleac and Krauss, who were charmed by the women’s enthusiasm for their art. Then, one day in 1935, Ursuleac introduced them to her friend Else (Mitia) Mayer-Lisman, an opera lecturer who would be visiting London, and asked that they take care of her. When the sisters naively asked Mayer-Lisman whether she was Protestant or Catholic, Vincent writes, “‘I?’ said Mayer-Lisman, rather surprised. ‘Didn’t you know? I’m a Jewess.’”

It was the moment that altered the trajectory of the Cooks’ lives. As Ida went on to become a fairly successful romance novelist under the pen name Mary Burchell, she used her royalty money to purchase a flat and sponsor Jewish refugees. Louise, shy and introverted, learned German, and together, they travelled into Austria over and over again, under the guise of attending operas staged by Krauss. Often, they returned to London covered in expensive jewellery entrusted to them by Jews who had purchased them with their life savings. The sisters reasoned that, draped in their Marks & Spencer clothes, border guards would assume the jewels were fake. And they were right.

“They knew that they were sort of plain and forgettable, and they used that as ammunition for what they did,” notes Vincent. “They knew the border guards would just look at them and say, ‘Oh, these crazy women, here they are again, coming to the opera.’”

Isabel Vincent. Photo by Zandy Mangold

It took years of dogged research and inquiry for Vincent to piece together the stories of the Cooks and of some of the people they saved. “Ida Cook was this prolific letter writer,” Vincent says. “She wrote to the divas that she loved…. I just kept finding correspondence around the world and used that to piece together what…they'd done before the war, during the war, and after.”

The great appeal of the Cooks, says Vincent, isn’t that they were remarkable people–but that they weren’t. “For me, the importance of the story was that Ida and Louise were like all of us,” Vincent explains. “They had no special anything, except this will to help people. Obviously, they were brave and they didn't let anything stand in their way, but they were pretty ordinary women who grew up typically middle-class and very sheltered. They could have just continued to be opera fans and forget about everything else that was going on around them, but they didn’t. I think that needs to be celebrated.”