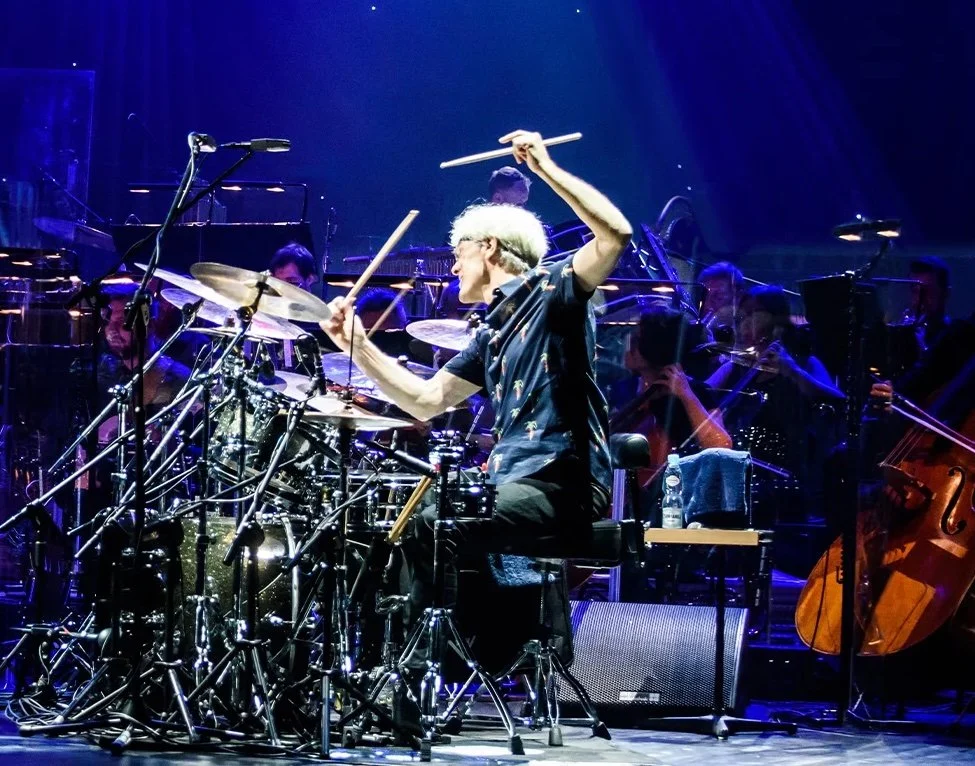

Legendary drummer Stewart Copeland brings symphonic power to Police Deranged

Joining the VSO, the icon uses his opera and film composition knowhow to recast hits from The Police

Rock royalty Stewart Copeland has fun “banging shit” with a full-sized orchestra in Police Deranged.

The Vancouver Symphony Orchestra presents Stewart Copeland: Police Deranged on September 30 and October 1 at the Orpheum

WHETHER HE’S COMPOSING elaborate operas to premiere at Germany’s hallowed Deutsche Nationaltheater und Staatskapelle Weimar or collaborating with Indian New Age composer-environmentalist Ricky Kej, legendary Police drummer Stewart Copeland is one rock star who won’t be retiring to a private island in the Caribbean any time soon.

“Are you kidding?!” he exclaims over the phone from his home in L.A. (We are, by the way.) “I just hit 70 years old and I. Can’t. Wait. to finish breakfast to get to work every day!”

The ever-energized Copeland has written five operas, video-game soundtracks, dozens of film scores, and a ballet. He regularly jams with everyone from Snoop Dogg to System of a Down’s Serj Tankian in his Sacred Grove home studio in L.A. (“where my fancy friends come to play”) for his YouTube channel.

All of which makes it noteworthy that we are actually here today to talk about The Police—the iconic trio that catapulted him to fame in the 1980s and secured his status as one of the (to many, the) world’s most-revered drummers.

Copeland is preparing to bring Police Deranged here—his new symphonic arrangements of hits like “Message in a Bottle”, “Roxanne”, and “Every Little Thing She Does Is Magic”—with the Vancouver Symphony Orchestra. He will take centre stage, “banging shit”, as he humbly puts it.

In some ways, Police Deranged brings the ever-busy artist’s many sides together—the kid who grew up listening to his archaeologist mother’s Ravel, Debussy, and Stravinsky records; the inspired orchestrator of operas and soundtracks; and the platinum-haired timekeeper who gave The Police its singular rhythmic sound of reggae downbeats and punk speed.

“The reason I’m so cheerfully going down this nostalgic path with The Police is because I’m also going forward—I’m writing new music all the time,” the hyper-quotable artist reflects. “I feel really good about the forward motion in my artistic development, so that makes me very casual about delving into the past.”

Copeland is having enormous fun with Police Deranged—but don’t let that fool you: his orchestral arrangements are incredibly sophisticated. The meticulous process of recasting the songs for a symphony was a world away from the way he remembers recording tracks for timeless classics like Outlandos D’Amour and Reggatta de Blanc. Back then, he says he’d listen to bassist Sting and guitarist Andy Summers work out a song for 20 minutes, then lay down his tracks within another 20 or so. Copeland is proud of the spontaneity and freshness that made those songs work.

“And by the way, I’m stuck with it: whatever I came up with in those 20 minutes is the record for my life!” he adds. “They got to redo all their parts, replay the guitar, re-sing the vocals, and everything. It may sound like I’m complaining. I’m not. It’s a brag. Subtle difference! I’m very proud and very intrigued, also, that the inspiration of the moment seemed to be so right.”

Orchestrating Police Deranged, as he did over the pandemic (as well as two operas), was a different matter. He wrote the symphony’s parts in intricate detail—reimagining the songs in elaborate new ways (see the trailer at bottom for a small taste).

“The volume of the orchestra is so much reduced compared to a rock band that my instrument—the drum set on which I bang shit—is actually much improved by that,” he enthuses. “The vocabulary increases enormously. All the ruffs and drags and ratamacues that I studied as a kid when my father forced me to have music lessons: they all have relevance now. The drum set against the volume of this orchestra has a huge vocabulary, so there’s all kinds of slickety-cool shit that I can do.

“And the interesting thing, sonically, is that even though the orchestra is not as loud as a rock band—at all, it’s about a third or quarter of the volume–the dramatic impact is greater,” he adds. “When you're sitting watching a big symphony orchestra, it feels as huge and impactful as a Megadeth concert, just because your ears tune into it. So for the drums to play in an orchestral setting requires a completely different technique–in fact it requires more technique!”

Stewart Copeland, at right, on The Police’s hit Regatta de Blanc album.

Every Little Nuance

What Copeland has come to love about writing for orchestras is the players’ absolute faith to every nuance that he puts on the page. “They are the mighty Vancouver Symphony and that's what they take pride in as their larger whole,” he explains. “Oh how do I love that as a composer! Which means while I’m banging shit, I can go anywhere I like. I can play it differently every night. They are solid, therefore I can be free.

“Which, by the way, was one of the problems between Sting and I,” he says, referring back to the famous tension that fuelled The Police’s greatest works. “For him to soar and fly like an eagle, he needs a solid platform from which to launch himself. And that’s not me! I am a completely un-solid platform, a moving platform, a constantly shape-shifting platform, and he never knows which foot he’s going to leap for the stars from because I’m somewhere different every night. God bless him, I try as hard as I can to give him that solid platform because I love it when he flies, but I’m just not that guy.”

For Police fans, Copeland promises that he knows how to make an orchestra rock. At the Vancouver shows, bassist Armand Sabal-Lecco joins the symphony, alongside the three singers. Copeland makes powerful use of the horns, the strings, four saxes, and his favourite instrument in the arsenal—the undersung bassoon, of all things: “It is actually the cutting edge of the bass line,” he asserts.

And as much as Copeland pushes ever forward in his career—unbelievably, as noted, the artist is now officially a septuagenarian—he recognizes the nostalgic effect The Police’s music has on its audience. Not to mention on the man at the drum kit.

“For one thing, I’m a sentimental old fool and I cry at dog food commercials,” he says with a laugh, “but on the other hand I’m also a student of not just music but the purpose of music. Why must homo sapiens do music? What is its function for humanity? And as a student of that, I learned that emotion and memory and music are all tied together with a very powerful bond….When you add those three things together to play an old song rather than a new song, it's very powerful. So these shows with the big orchestra and the songs that these people know and me banging shit: it actually adds up to a pretty fun night.”

It also speaks to the fact that Copeland continues to love banging shit—and arranging “slickety cool” orchestrations—well into the future.

So Police fans across the generations want to know: what’s his secret?

“I’m always interested in stuff, and that's not because I’m a wonderful person—that’s what I was born with,” he says. “I regard musical talent as a gift—an unearned gift for which I am very grateful. And by the way! Just because you don't get the same gift that I get doesn't mean you can’t pick up a guitar and strum on it and transport yourself with music the same way that I do. You don't need my chops to play music. I'm a big believer in campfire music—music made by all of us human beings. We’re not all Eric Clapton. But music is really fun and powerful even if you don't have a special gift for it.”