Art review: Polygon Gallery's Third Realm finds haunting relevance amid pandemic

A million black business cards, saddles bearing megaphones: Asian works offer heightened sensory experience

At Third Realm, Apichatpong Weerasethakul’s Ghost Teen sits to the left of Jompet Kuswidananto’s Third Realm Venice Series #2, Pilgrims & Plagues single channel video, and Family Chronicle #1. Photo by SITE photography; artwork courtesy FarEastFarWest collection

Third Realm is on view at North Vancouver’s Polygon Gallery until November 8

SUSPENDED LEATHER bridles, saddles with blonde horse tails, a couple of drums and marching band hats, and two pairs of boots form a beautifully haunting installation that catches your breath on entering Third Realm at North Vancouver’s Polygon Gallery.

A megaphone floating above one of the saddles suggests a figure atop a horse. On closer look, the boots are Converse-like sneakers. The bodiless costumes suggest a military band or festive parade in procession, without referring to a specific event.

Also titled Third Realm Venice Series #2, the 2011 work is by Indonesian artist and musician Jompet Kuswidananto. Flanked by Apichaptong Weerasethakul’s Ghost Teen, a 2009 mural-sized image of a teenager behind a gory zombie mask, and the same year’s The Field, another mural print of a field set ablaze, the installation engulfs you.

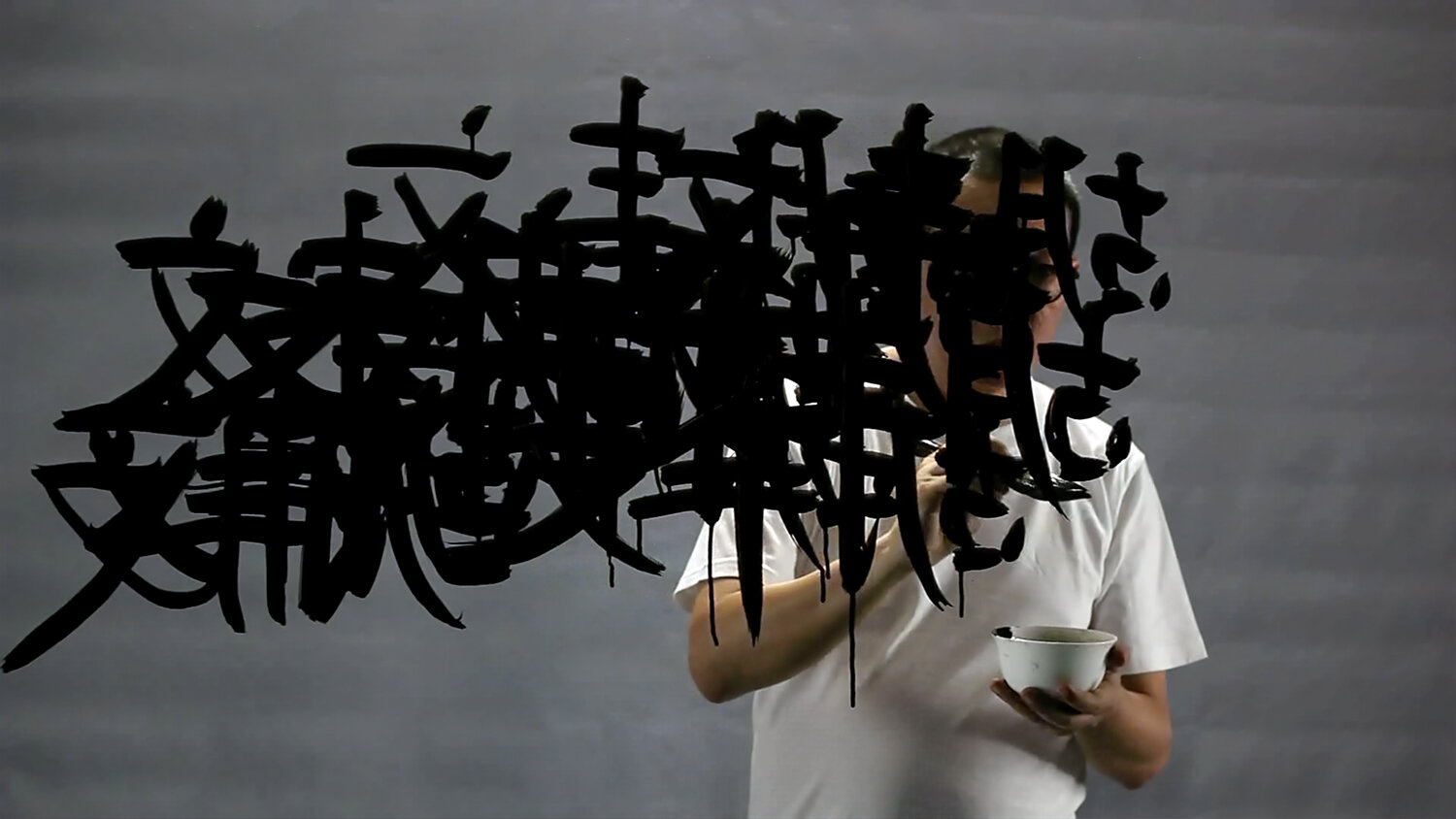

Elsewhere in the exhibition, one million black business cards, all blank, fill an adjacent space in Heman Chong’s 2008 work Monument to the People We’ve Conveniently Forgotten. You have to tread carefully over the slightly slippery cards in order to view the other works in the room—FX Harsono’s mesmerizing 2011 video Writing in the Rain and Sutee Kunivitachanont’s neat row of photographs of billboards that play on Western stereotypes of Thai culture.

One million black business cards carry a dark message in Heman Chong’s Monument to the People We’ve Conveniently Forgotten (I hate you). Artwork courtesy FarEastFarWest collection

Originally scheduled to open at the end of March, Third Realm was postponed, of course, due to the global pandemic. As the first art exhibition I’ve seen in-person in six months, the exhibition offers a heightened sensory experience that is impossible to replicate virtually.

Curated by Shanghai- and Italy-based Davide Quadrio, the impressive group show brings together 16 artist projects—many performance-based—that address contemporary issues in Asia, and produced between 2004 and 2019.

Jompet’s ghost parade, viewed together with two of his large-scale videos and a series of photographs, explores the artist’s ongoing research into Indonesia’s colonial history and modernization. He explores Indonesia’s identity as defined by a constant in-between state. Investigating dichotomies—tradition and modernization, global and local, past and present, sacred and secular—and what lies in-between, sets the premise for the exhibition.

There are subtler pieces that require detailed attention and others that are laugh-out-loud funny, too. Crazy Bird series by artist duo Birdhead, for instance, invites you to lean in and look closely. The photographic installation comprises black-and-white snapshots of daily life in the rapidly changing Shanghai, the artists’ hometown—apartment towers, and traditional Chinese gardens with pagodas and trees. The photos are encased in hand-made wooden frames and displayed salon-style, tacked onto the wall with exposed hooks and nails. The artists, who appear in some of the images, use everyday materials such as coloured craft glue and staples to embellish the photos. Some are placed behind glass held by folded metal tabs, the kind behind cheap IKEA frames. Others are stamped with a traditional Chinese red seal with the character for “love”. Birdhead was formed in 2004 by artists Ji Weiyu and Song Tao, who work collaboratively. They go around the city taking photographs, calling it “sports photography”, and capture whatever is meaningful to them. The individual photograph, like its authorship, is unimportant. It is instead a fragment of a whole.

Red Dogs, by Apichaptong Weerasethakul is a 2010 multivideo installation that can easily be lost. Tucked away in two corners of the gallery, the work is projected close to the ground at dog height. You have to bend down to read the art tag. It shows movements of a stray dog, blazing orange-red, as if filmed through a thermal imaging camera. It flickers in and out like a dream or memory, tying into the artist’s large mural prints that explore recollections of Nabua, a village in northeastern Thailand close to where the artist grew up, through its violent history from the 1960s to 1980s.

FX Harsono’s Still from Writing in the Rain, at Third Realm. Courtesy FarEastFarWest collection

Humour finds its way into the exhibition in Zhou Xiaohu’s three “camp” videos. Bring your own headphones to plug-in or borrow a sanitized pair from the bookstore to watch them in full. They’re hilarious. In Crazy English Camp (2010), a real-life Crazy English teacher, dressed in a suit and tie, stands on a platform and leads a large crowd in red collared shirts into shouting random phrases in English with conviction. They copy hand gestures that mimic the sound of each syllable—”EEEEEE, EEEEEE, EEEEEE, TEEEEEAM”—and practise perfecting tongue positions to produce sounds—”TH, TH, TH”. Behind the teacher we see the phrases “I’m so proud of this team. This team is crazy. This team is strong. This team is passionate.” Overhead is a red banner with Chinese characters and an English translation underneath that reads “Help 300 million chinese speak good english. Make the voice of china heard throughout the world.” The video, a staged performance for 2010’s No Soul For Sale—Festival of Independents at Tate Modern’s Turbine Hall, explores Crazy English. A method created for Chinese audiences by Li Yang, shouting equates learning. Crazy English peaked in popularity leading up to the 2008 Beijing Olympics. Volunteers underwent Crazy English training camps as China prepared to welcome the world. The performance, set in an English-speaking country with a largely white, presumably English-speaking crowd, is then totally bizarre, revealing more about crowd mentality than learning English.

Upside-down Amway actors and globalization

Concentration Training Camp, a 19-minute video from 2010, follows a fictional group of Amway employees during their training at the American company. The video is divided into a series of training activities and team games—No. 3 Fortune Forum, No. 4 Shared in Tear, No. 5, Devise Strategems Together. The employees, dressed in jeans, black turtlenecks, or white shirts, move about awkwardly, stiff-necked with hair sticking up. They float in slow motion and freeze in place. They’re led to recite motivational phrases reminiscent of communist propaganda, directed to clap in unison, or told to perform other team drills. The actors, in fact, hang from a concealed suspension system and are then filmed upside-down to appear upright. China is currently Amway’s largest market, accounting for one-third of its global revenue, which in 2019 was US$8.4 billion. Earlier this year, as factories closed across China to slow the spread of COVID-19, Amway was granted special permission to reopen in order to meet the country’s demands for its health supplements. Training and sales continued virtually.

Apichatpong Weerasethakul’s The Field. Courtesy FarEastFarWest collection

While the exhibition investigates artistic response to rapid globalisation in Asia in the mid-2000s, many of its themes and the issues have new relevance in light of the global pandemic. We can’t help but add new ways of reading the works as the world’s eyes have once again shifted to China. We can add a new dichotomy here: before the pandemic and after the pandemic. Third Realm is well worth a visit.

Apichatpong Weerasethakul’s Ghost Teen. Courtesy FarEastFarWest collection