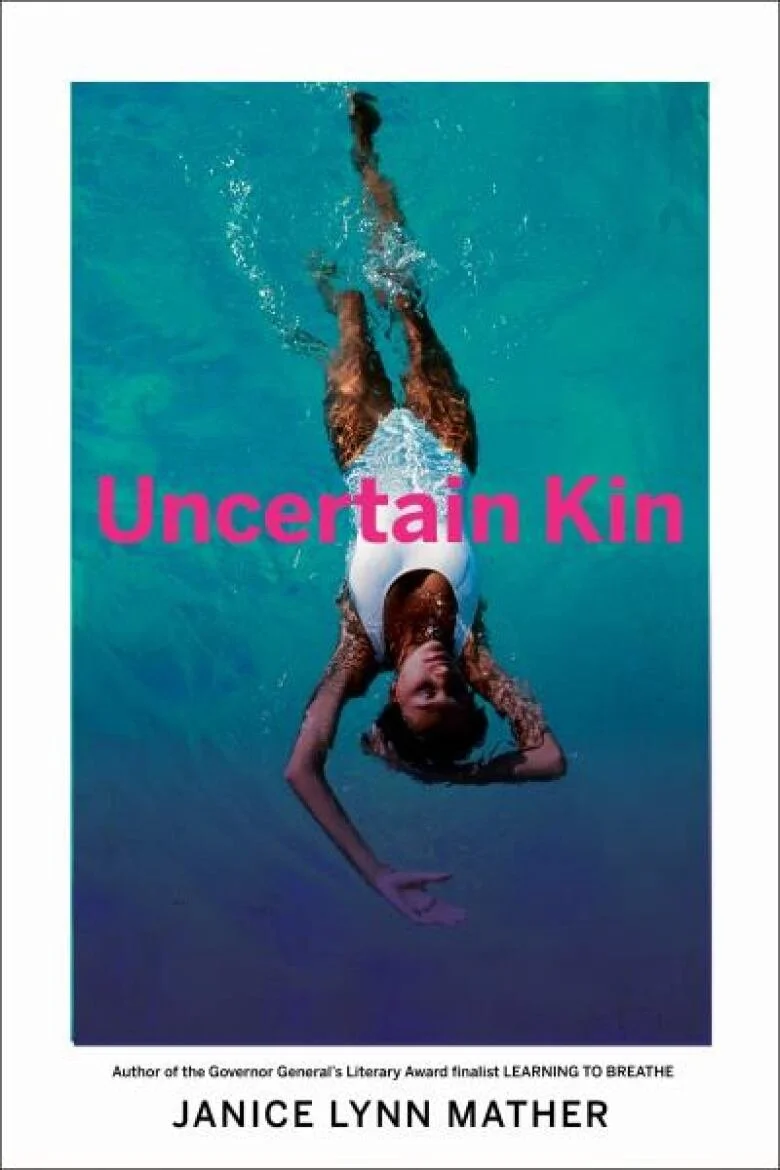

Scents and sounds of Bahamas, as Janice Lynn Mather writes short stories through the eyes of girls and young women

In her new Uncertain Kin, Vancouver-area-based author conjures island life through vivid memory

Janice Lynn Mather. Photo courtesy Doubleday Canada

IN “MANGO SUMMER”, one of the indelible new short stories in Uncertain Kin, Vancouver-based author Janice Lynn Mather doesn’t just take you to the Bahamas–she makes you smell it.

Mather writes that “sugar apples melted off trees and lay open on the ground, splattered buffets left for the rats.” People left bags of “sickly ripe” mangoes on their neighbours’ doorsteps, the August humidity “so tight with smell it hazed orange”.

They say one of your strongest memories is scent, and that seems to hold true for Mather, who moved to Vancouver in 2002 and pursued her BFA and MFA in creative writing at UBC, and who has been distanced from Bahamas during the pandemic. Taste is a close second—baking and jam and sour meats with rice and beans—and you can hear and feel the place, too: the sound of a cutlass clinking against a metal fence as it slices through grass; the sensation of sitting on a cool washing machine to escape the heat.

Mather allows that distance may bring some of those sense memories into relief, or into heightened perspective. Like so many of the affecting and unsettling stories about girls, their mothers, aunts, “grammies”, and neighbours in the aptly titled Uncertain Kin (just released by Doubleday Canada), the facts have been altered from her specific experience growing up in The Bahamas. The fruit in Mather’s family’s back yard had actually been guavas.

“I do remember summers in my childhood home when we had all these guava trees and it did become extremely excessive,” she begins with a laugh, speaking to Stir from her home in Tsawwassen. “There’d be worms through them, and then they'd fall and you'd go out and see that the rats had been feasting on them—on these overripe, rotting guavas—and then you’d see this whole little forest of extra guava trees that would start to sprout out of it before the fruit was even all rotted. So there are those memories you have, and when you're away from a place and you think about them, you still have that scent memory.

“And then, the first time I found really good guavas in Vancouver, I was living in Marpole and was walking by Granville and 70th. I stopped in my tracks and went back into the produce store. My nose had taken me right to the guavas. And it was like being back in my back yard,” she continues. “So you have those things that you don't necessarily think of in the same way when you have them all the time. And it’s with absence and with distance that you realize how much it meant to you.”

That separation also allows the writer to ply territory she might not feel totally comfortable exploring if they still hit close to home. Uncertain Kin explores some difficult subject matter—grief, betrayal, trauma, exploitation, teen pregnancy. Not all of these haunting yet full-hearted stories are set in The Bahamas: one focuses on an immigrant mother struggling to plant roots in Vancouver.

“A lot of the stories circle around secrets or things that people don't want to talk about; things that everyone knows are going on but that no one is acknowledging in conversations,” Mather says. “I think sometimes to have a little bit of space allows you to say, ‘I’m doing this and I can't get into too much trouble,’ because there’s not as much immediacy.”

Mather is a well-known author for young adults, her Learning to Breathe a finalist for the Governor General's Literary Award and her Facing the Sun winning the Amy Mathers Teen Book Award. Even here, in a book that transcends that genre, she often focuses on the world through the eyes of girls and teens who are coming of age. In the unsettling first story, “Centipede”, a school girl tries to process the reason her Grammy sends her, but not her teen sister, out of the house and closes the curtains when a repair man comes. In “Glory”, almost-15-and-pregnant Priscilla navigates having to stay with a Grammy who says she’s brought shame upon the house. In “Malcom’s Shoe”, a girl struggles to comprehend her older brother’s beating in the middle of the night.

“I think it's a key time of life, especially when you are on that edge of childhood, or on that edge of womanhood,” she says. “Are you child or woman? It depends on who’s looking at you and what their interests or fears or suspicions or judgments are—what they're looking to make you into or get out of you. I think there are a lot of really important and sometimes painful questions around that age.”

In these stories written over years, and revised meticulously during the pandemic, Mather’s craft shows itself in restraint—in the way certain details are never explained, often because the characters themselves don’t quite understand the whole picture. As adult readers, we’re left to unravel and mull over the information in front of us.

“You're kind of bewildered and really not knowing—children are always seeing and hearing things, and there's not always a ton of effort put into shielding us from things,” Mather reflects. “Sometimes adults think they’re doing great jobs at keeping things under wraps, but they don't necessarily.

“Looking back as adults at how we interpreted and tried to make sense of things, I think many of us may be able to relate to information having been missing from experiences we had as children or things that we saw that our adults didn't know what to do with themselves,” she adds. “They weren't equipped, and we were even less equipped.”

Interwoven is the sense that sometimes what’s happening in these short stories may be beyond earthly knowledge–that some mystical, surreal, magical, folklorical, or even Biblical force may be involved, and that events may or may not have a logical explanation. Why are girls disappearing, seemingly into thin air, during that heavy, humid mango summer? And why does bright-red blood pour from Nassau’s taps after a pastor gives a fiery sermon?

“Depending on who you talk to and where you are in the world, people will speak with greater or lesser certainty in the validity of dreams or messages that they've received from someone who has passed on or what certain odd natural happenings mean,” Mather says. “For one world view, it might be ‘Oh, the insects are swarming; they do that once a year’ and for others it’s a sort of an ominous warning.”

And so it is with the overwhelming scent of rotting mangoes—or guavas, as the case may be. In the book, that humidity, that odour, makes people act strangely. And whether that’s a logical occurrence, or there’s a more mysterious, possibly sinister force at work, the pleasure of reading Uncertain Kin is that some of its secrets are left unspoken.

“‘Mango Summer’ is one that’s extra dear, and even I don't know all the details of all the details of what's really happened at the core of the story,” Mather says. “When it comes to certain kinds of community tragedy, there often are secrets at the core of a community.”

And the kinds of secrets she’s talking about happen far outside her very specific and detailed Bahamian settings, the writer adds: “Those topics exist for every community and culture and country, to different degrees.”