Conductor Kari Turunen celebrates the respite and honesty in choral works of Arvo Pärt

The Vancouver Chamber Choir brings to life 25 years of the living legend’s work

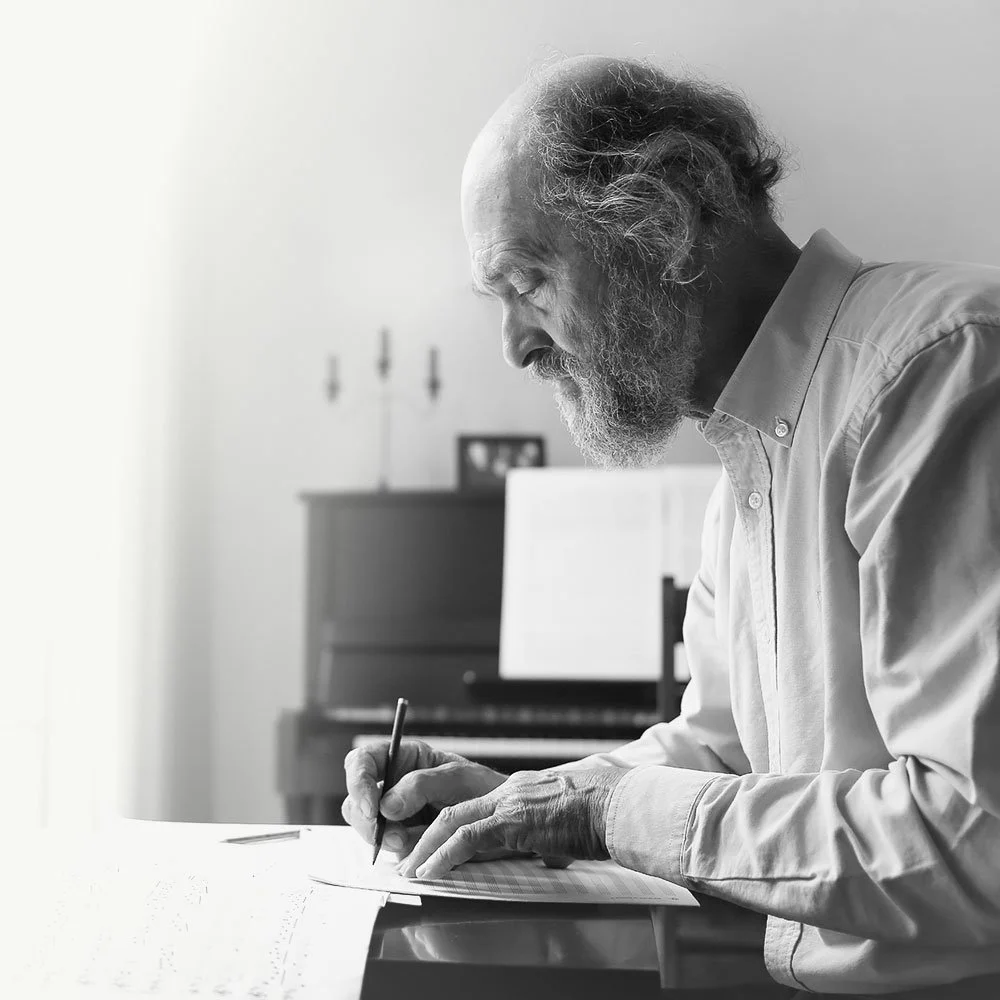

Vancouver Chamber Choir artistic director Kari Turunen

Arvo Pärt. Photo courtesy Arvo Pärt Centre

Vancouver Chamber Choir. Photo by Diamonds Edge

The Vancouver Chamber Choir presents Pärt at Pacific Spirit United Church at 11 am on October 28 and 7:30 pm on October 29

FROM A DISTANCE of almost 40 years, Kari Turunen recalls the first time he heard the music of the Estonian “Holy Minimalist” composer Arvo Pärt.

“It must have been the early 1980s, and it was a very simple piano piece, Für Alina, which was the first thing he’d written after his self-imposed silence of many, many years,” the affable Finn reports. “And then I heard Credo, the version for singers, very early as well, and I was really struck by it. My first thought was ‘How dare anyone write music like this?’

“In music circles, ‘the more complex, the better’ was still the aesthetic, and it was radical to write something beautiful,” Vancouver Chamber Choir’s artistic director explains. “It was almost unheard of, and yet at the same time it felt so honest and real. It seemed like ‘Here’s someone with something to say. I don’t know what it is, but I can hear him orchestrating it.’ And that’s never really disappeared through the years. I still feel that, despite Pärt’s early technique being very, very simple. Anyone could write music using that technique, but it just feels that with Pärt there’s something behind it, that the composer is really trying to speak to me.”

Turunen was not alone. Within a few years, Pärt became one of the world’s best loved living composers: in addition to helping spark a move towards radical simplicity in contemporary composed music, his approach has inspired rock bands and writers of Hollywood soundtracks; even his serene if weathered visage, with its aura of monkish otherworldliness, has become iconic. The international success of early recordings such as Tabula Rasa and Litany has essentially bankrolled his record label ECM’s new-music division, now home to such significant classical artists as András Schiff and the Danish String Quartet. And that such a talent could emerge from a small Baltic nation has also driven a wave of interest in the music of the region, especially its rich choral tradition.

Turunen himself has probably profited from this last development, and he’ll get to pay homage to Pärt this week, when he’ll lead the Vancouver Chamber Choir, with organist Christina Hutten, through two concerts of the living legend’s music.

“It’s sort of a retrospective,” Turunen notes. “The earliest work, a version of An den Wassern zu Babel saßen wir und weinten, is from 1976, and then the last work that we have on the program is from the early 2000s. So it covers roughly 25 years of his work—and you hear the evolving happening in front of your ears, from the simplicity and the utter concentration of An den Wassern to pieces like the Salve Regina, which I think is almost Romantic in essence and doesn’t seem to use the same technique any more, although it’s there if you choose to look a little bit under the surface.

“And then there’s a work like Which Was the Son of…, which I think shows a completely different side of Pärt. It’s actually quite funny, in a Pärt way. It’s hard to explain, but it definitely has its moments of humour, and the whole concept of the piece is that it was commissioned by an Icelandic choir. He wanted to write a piece which reflected the Icelandic patronymics and matronymics, so he listed the genesis of Jesus. ‘Being the son of Joseph, which was the son of Heli, which was the son of Matthat, which was the son of Levi.’ It’s probably the most idiotic text I can think of, but he pulls it off pretty amazingly.”

The spirituality in Pärt’s music is generally less droll, rooted as it is in plainsong and the liturgy of the Russian Orthodox Church, but Turunen points out that one does not have to be a believer to find solace and inspiration in sound.

“The sanctity of his music, if you like, is fairly human,” he says. “Perhaps I can put it like this: a lot of classical music traditionally stems and speaks from a position of power. It’s funded by a patron, and it’s to the glory of the patron and of God and so on. But I’ve always felt that Pärt’s music speaks from a position of humility, and I think that makes it approachable for anyone, anywhere. It is always very close to things like sorrow and suffering, so I think I’ve never felt that it’s exclusively religious. It’s more generically spiritual.”

Another aspect of Pärt’s appeal, Turunen adds, is that his often deeply meditative approach offers genuine respite from the fast pace of modern life.

Pärt is one of a handful of living contemporary composers “who approach time a little like medieval music or Renaissance music, where time is stretched out and events take much longer,” he explains. “Which somehow, in this time, creates a different time zone to step into.…For 10 minutes you’re allowed to wallow in this world, which just seems to have a different pace. I think we feel that in much music: when we go to concerts we enjoy the fact that we have time to just be in our own thoughts and be still. But this is taking it to the next level.”

It’s a stressful time in our world right now, and a chance to bask in Pärt’s next-level luminosity could well be what many of us need.