Dance review: Striking imagery and a powerful Crystal Pite piece at Ballet BC's season-opening DAWN

A standing O for Frontier’s awe-inspiring visual magic and multiple, moving layers of meaning; plus, an erotically charged Heart Drive and an ever-shifting Cloud Poem

Ballet BC dancers Rae Srivastava and Jacalyn Tatro in Frontier by Crystal Pite. Photo by Michael Slobodian

Ballet BC’s DAWN continues at the Queen Elizabeth Theatre to November 9

FOR THE CRYSTAL Pite fans who turned out in force to Ballet BC’s sold-out season opener, the internationally in-demand Vancouver choreographer definitely did not disappoint.

Her dramatically striking Frontier closed the company’s DAWN program, preceded by two other decidedly cinematic-feeling pieces—Heart Drive by the Netherlands’ Marne and Imre van Opstal and Cloud Poem by Paris’s Pierre Pontvianne.

And as interesting as the other two works were, it makes sense to start with our homegrown star showing a major piece that’s never been seen here before. It was clear from the opening moment of Frontier that audiences would be in for a fully realized vision from the choreographer behind Kidd Pivot hits like Assembly Hall and Betroffenheit, not to mention Ballet BC favourites like The Statement. Out of the darkness after intermission, 20-odd hooded shadow figures, dressed and masked in black, scrambled up from the audience and rolled over the edge onto the stage.

From there, Frontier displayed Pite at the peak of her powers: awe-inspiring visual magic, intricately carved-out choreography, and—most importantly—multiple, moving layers of meaning.

These kabuki-esque “puppet masters” at times manipulated other, unmasked dancers, dressed in white. The shadow figures hoisted them skyward, moved their arms and legs, or, in some of the most striking moments, turned and lifted them sideways, carrying them around like stiff porcelain figurines.

Pite has said the hooded creatures represent the unknown, the dark matter of the cosmos, or simply all-too-relatable human doubt. They were mysterious and sometimes sinister—but they also supported the dancers in white, occasionally mirroring their movement and dancing in unison with them. At key moments, the “humans” turned the tables on them, managing to wrestle these embodied fears down.

Frontier has never been seen in North America before, and for dance fans, it was a revelation. The piece was originally commissioned for Nederlands Dans Theatre, where Pite is a celebrated associate choreographer, but she’s renovated and expanded it for Ballet BC (with an expanded corps that includes Arts Umbrella dancers) to smashing effect.

The work was bookended, as in the original, by Eric Whitaker’s soaring choral works, but Vancouver composer Owen Belton has rebuilt the central score with a haunting soundscape of human whispers, breathlike exhalations, and skittering consonants. Adding to the eerie feel were Jay Gower Taylor’s set and Tom Visser's lighting. Transparent screens enclosed the action, suggesting a veil between worlds. A thin frontier between the conscious and unconscious? The known and unknown? At times, rows of lights behind the scrims illuminated imposing silhouettes of the shadow figures. And then, with the blink of an eye, they were gone again.

There was gorgeous, inventive partnering—at one point a few shadows hoisted a languid, liquid Pei Lun Lai—and some power-packed solos. But what was most stunning was how Pite’s choreographic chops and these honed, magnetic dancers combined to give the masked, anonymous shadows in loose black sweats such personality and motivation. The shadows’ group work was also amazing, the figures sometimes scattering like a mass of ants, other times pooling like a blob of pulsing primordial ooze.

Full of visual surprises and truly affecting ideas—who hasn’t felt the weight of some unknowable force manipulating them?—Frontier built to a strange and satisfying finale that brought the packed Queen E. to its feet with loud applause and cheers.

Ballet BC dancers Kiana Jung and Michael Garcia in Heart Drive by Imre and Marne van Opstal. Photo by Michael Slobodian

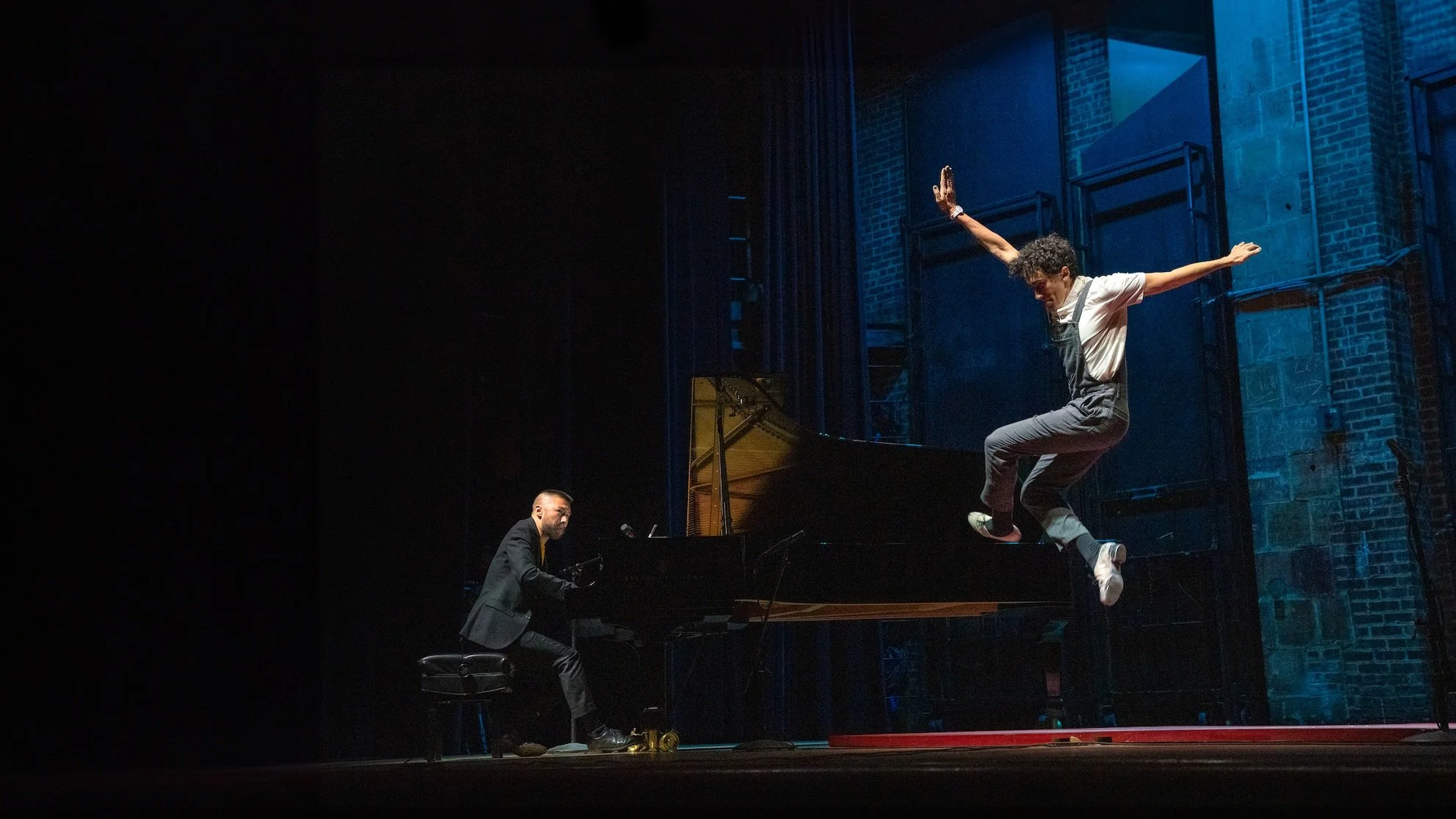

Frontier mixed well with the other two offerings on the DAWN program. The van Opstal siblings’ erotically edgy Heart Drive made a welcome return, the dancers back in their squeaky, leg-baring PVC leotards, harsh splinters of light reflecting coolly off them in the opening moments.

A second look at the work brought a new appreciation for its demanding choreography, the dancers fully committing to its pelvic thrusts and deep, sensual lunges, slinking around on all fours and partnering in the most rawly sexual yet empowered ways—legs scissoring wide, torsos entwining, hands finding buttocks and the smalls of backs.

The Dutch choreographers built geometric space out of unique triangular light, animated by swirling smoke imagery to match the heat that was happening onstage. Guitar reverb and slow-build beats drove the partnering. At other times dancers, lying prone, flapped forward like the world’s sexiest fish. Michael Garcia was one of the fierce standouts, limbs windmilling; in one logic-defying split-second, he somehow switched from standing upright to lying on the floor, propping himself up on his elbows. His ferocious pas de deux with Kiana Jung was one of the highlights of the night.

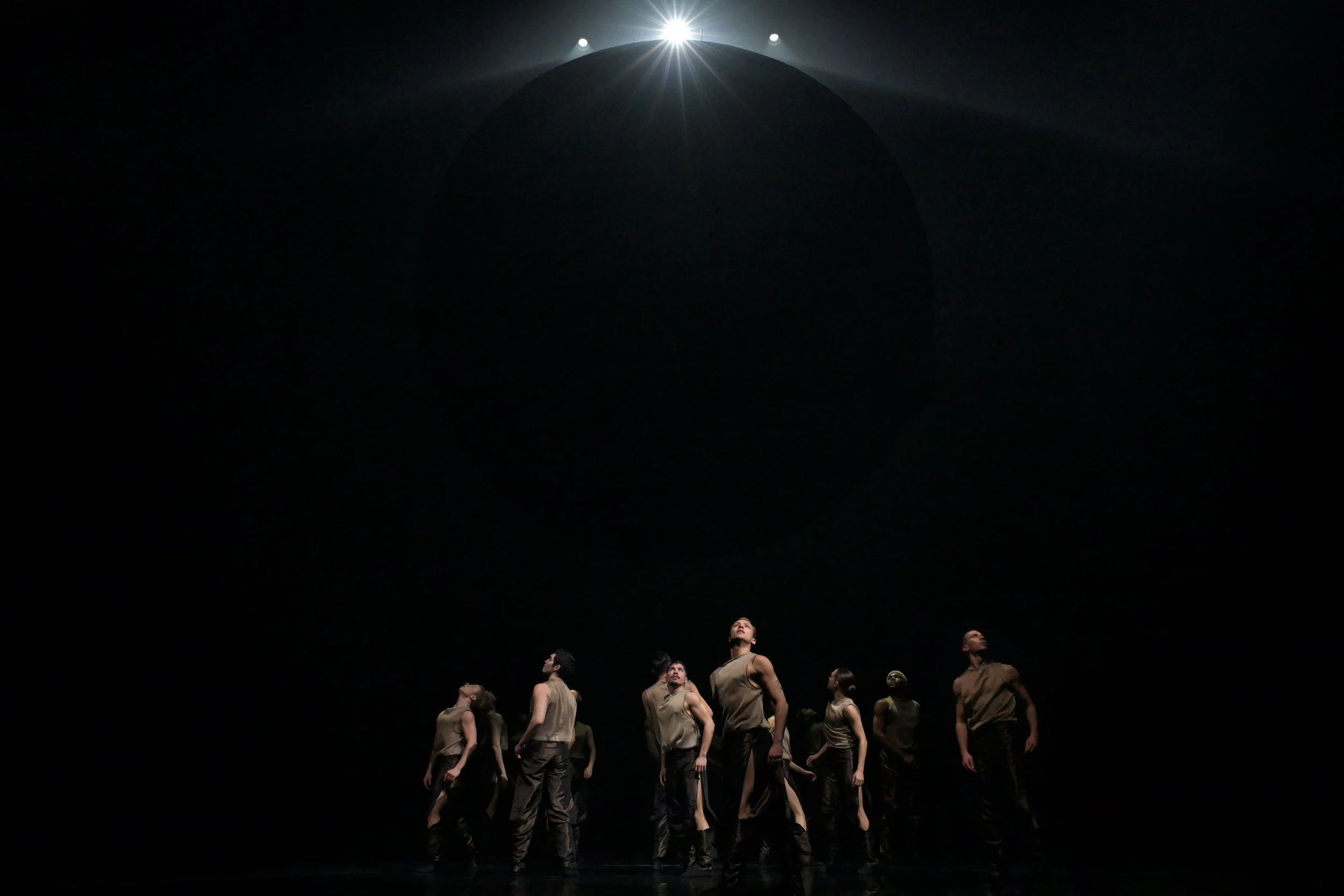

Perhaps the evening’s most filmic offering was the world premiere by Paris’s Pierre Pontvianne. His Cloud Poem contrasted imagery of the lone individual against the group. The opening moments captured dancers in a stark spotlight that intermittently turned on with a startling sonic roar. Later in the piece, performers shifted and morphed like the clouds of the title, bodies turning and lifting asynchronously to create amorphous shapes—all set to a delirious soundscape (also by Pontvianne) that suggested everything from sampled crickets to faraway thunder. At times, the corps swayed together like kelp caught in some kind of cosmic tide.

Artists of Ballet BC in Cloud Poem by Pierre Pontvianne. Photo by Michael Slobodian

Foreshadowing Pite’s piece, dramatic changes in lighting suddenly changed our entire perception of what was going on onstage; in the most discombobulating sequences, figures danced in front of a grey void, throwing static-y shadows. True to its title, Cloud Poem felt like it was more about sensations and shifting points of views and patterns, rather than reaching for larger metaphors.

Across the board, these were works that took artistic risks and prodded dance beyond abstract movement into entire dreamlike worlds—heavily informed by film and conceptual visual art. But, particularly in Pite’s Frontier, the pieces also demanded superhuman strength and versatility from their dancers. And this increasingly world-renowned corps, with several fresh faces, met the challenges, looking tighter than ever as it launched its season. Doubts, and shadows, seemed to be fully under control. ![]()