At Matriarchs Uprising, TOA III draws inspiration from Māori martial arts

Having its world premiere at the fest, the work merges the ancestral knowledge of mau rākau with contemporary dance

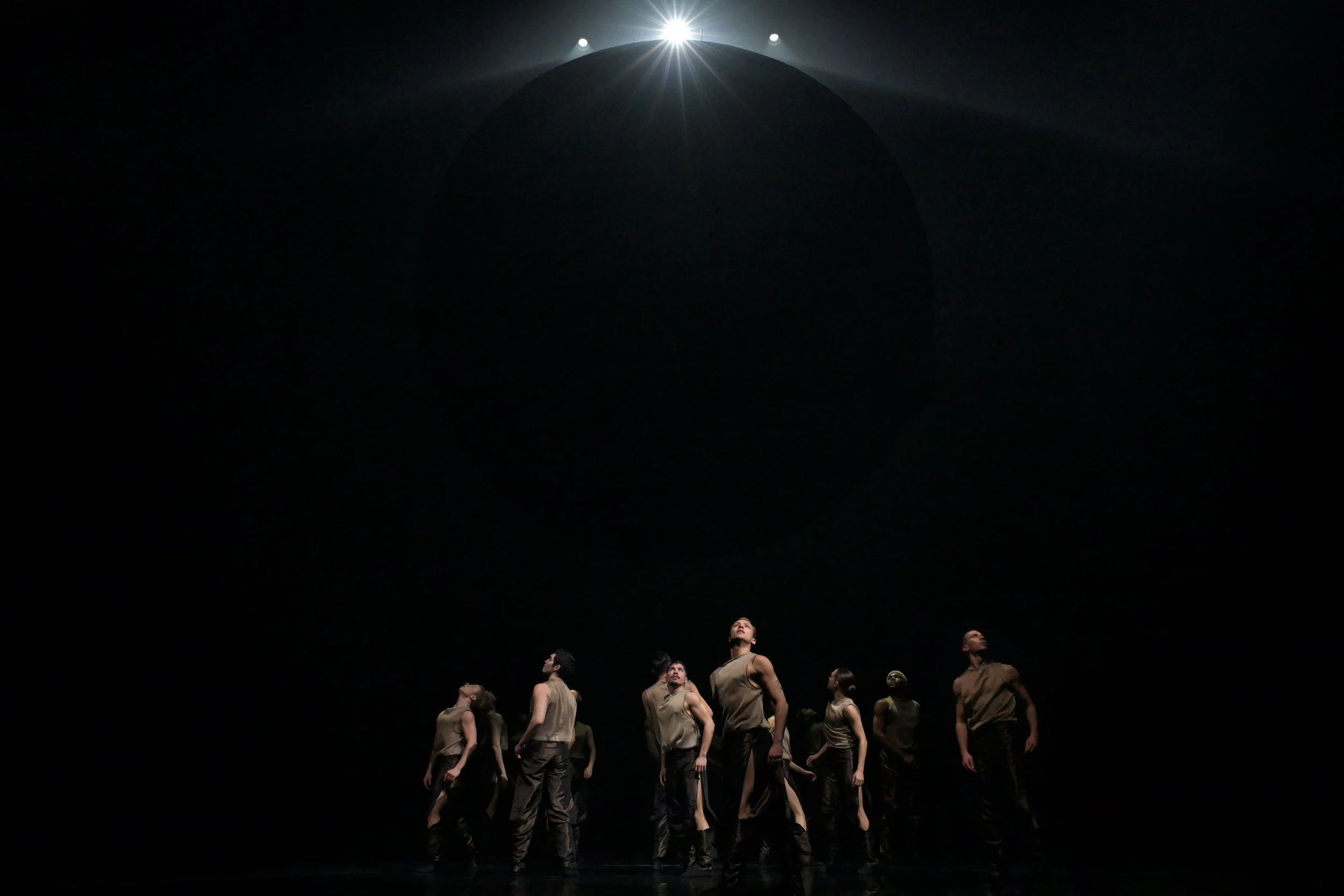

TOA III. Photo by Sol Fernandez

Matriarchs Uprising presents TOA III at the Scotiabank Dance Centre on February 22 at 8 pm

MAU RĀKAU IS a traditional form of Māori martial arts that was nearly lost through the British colonization of New Zealand. It was outlawed for 60 years under the Tohunga Suppression Act of 1907.

Its revitalization was encouraged just over 40 years ago through the establishment of Te Whare Tū Taua o Aotearoa, the international school of Māori weaponry, which aims to revive Māori language; wisdom; and cultural, spiritual, and ceremonial practices. It’s also a style that Birraranga/Melbourne-based dance artist Bella Waru—who is of Ngāti Tukorehe, Te Āti Awa (Māori), and European descent—has spent the last four-and-a-half years studying.

“I always wanted to do something that was about learning more and connecting more deeply to my culture,” Waru says in a Zoom interview with Stir. “As a dancer and a performer, I really wanted to do something that was embodied, something I would be able to have in me.”

Waru has teamed up with two other women who practise mau rākau, Fallon Te Paa and Kaycee Merito, to create TOA III, a new dance work that will have its world premiere at Matriarchs Uprising, a celebration of contemporary dance by Indigenous women artists. Curated by Olivia C. Davies, this year’s lineup also features dance works by Vancouver’s own Raven Spirit Dance, which will be premiering its newest creation, Tracing Bones; Lara Kramer, who returns to Vancouver with Gorgeous Tongue; Christine Friday, who brings the Western Canada premiere of Bawaajgun: Visions IN Dreams, created in collaboration with champion hoop dancer Beany John; and O.Dela Arts artistic associates, who share a program of new works including naⱡa by Samantha Sutherland and all roads lead home 3.0 by Sophie Dow.

TOA III runs on February 22 at the Scotiabank Dance Centre. The work’s creators draw from the ancient language of mau rākau and merge it with contemporary dance. Waru explains that “toa” means a few different things; it signifies “warrior” and can also imply being “brave” or “strong”.

“As a dancer and choreographer who’s existing in the contemporary-arts space, I’ve seen a lot of work that kind of speaks to and references warriorhood by people who don’t necessarily practise those things,” Waru says. “I was very moved to articulate what it means to be a modern-day warrior or to exist in the world in a way where you are embodying and practising the qualities [of a warrior], and facing the challenges of what it means to face our fears and face challenges head-on, to move through pain, to persevere under all circumstances: all these qualities that are embodied in this craft. I was interested in going really deep into what those qualities and experiences are and to tell that story from our perspective.

“Māori people are a people who are often stereotyped as a warrior people, which is very singular,” Waru adds. “I think a lot of the time it doesn’t offer us the depth and the multiplicity and the true range of what being Māori actually means and looks like.”

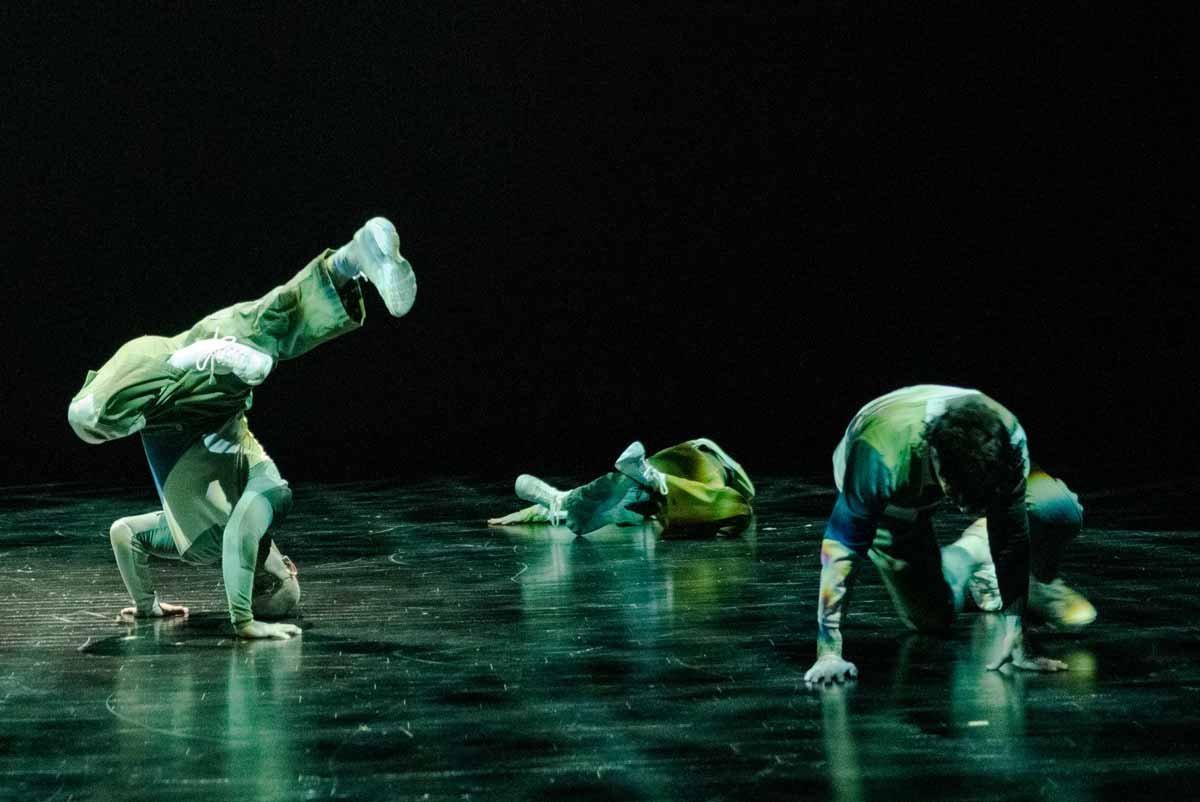

TOA III, Bella Waru. Photo by Jacinta Keefe Photography

Waru says that TOA III offers a fresh take on what it means to be Māori. “I think that this work being presented by three femmes offers a different perspective; the narrative is often fronted by men in our culture,” they say. “I’m queer and both of my collaborators are women and mothers, so having this story told by people who come through the matriarchal line and who have that experience is offering a different side to the story. It’s us passing on our experiences and the things we’ve learned.”

Waru explains that they were motivated to study mau rākau after spending time in Singapore, where they attended a martial-arts workshop. The instructor there gave them a spear to work with. Although an entirely different style, mau rākau also incorporates a similar kind of weapon.

“We use a long wooden staff,” Waru notes. “When he gave that to me, it felt like I already knew how to use it. I had never done it before, but it was like I was remembering something. When I did that, I knew I wanted to come back and do Māori martial art. I really felt a strong affinity for that.”

Waru emphasizes that TOA III is not a literal illustration of mau rākau; rather, the work uses “ghosts and echoes” of the form that reverberate throughout the work. “I was really interested in how we could articulate what it means to be in the world that we are in and the things that we’ve learned from that without just doing the thing that we do,” Waru says. “Otherwise you’d be watching martial arts and not a dance work.”

Practising mau rākau has had a tremendous impact on several aspects of Waru’s life. They say it has changed the way they make decisions, the way they walk through the world, and how they strategize.

“The school I practise at was designed not to make fighters but to make leaders for our community,” Waru says. “I feel like the things we learn through this craft are so valuable to our own people. It’s really important to navigate all the things the world is throwing at us right now. I feel like this knowledge is a gift we can share. I hope people can see themselves reflected in the work. I think it’s a beautiful thing to be able to articulate these moments in history back to our own people and to the world and to others as well.

“I feel like right now in this cultural and political moment, there’s so much globally that Indigenous peoples are fighting for,” they add. “We’re kind of in a moment right now even in our own base here where I’m seeing or experiencing an influx of women and queer people into the craft. History is being made for our people right now. So I think telling this story in this moment is our experience of what’s happening and it’s the documenting of a moment in our cultural landscape, which is important.”

Waru notes, too, that the instruction of mau rākau happens in the Māori language, which has helped them with their command of their native tongue. Their father was of the generation that was prohibited from speaking their traditional language.

“Everyone in that space is on a journey of cultural reclamation and language reclamation,” Waru says. “Everyone is invested….This immersive experience has really shifted my cultural understanding. My cultural literacy and feeling of connection and confidence in my culture has grown significantly.”

Waru’s hope for TOA III is for people to have a new experience.

“I want people to come and just feel the work less than think about it,” Waru says. “That’s what I would hope for. What was really exciting for all of us was melding the worlds of the contemporary and the traditional. The traditional practice is in there, but it’s all introduced in different ways that were exciting for us. It was opportunity to play.” ![]()