Kim Kennedy Austin takes a handcrafted approach to social commentary in Booster Club at Burnaby Art Gallery

The artist’s work draws equal inspiration from Sinclair Lewis’s 1920s novels and ’90s dystopian sci-fi flicks

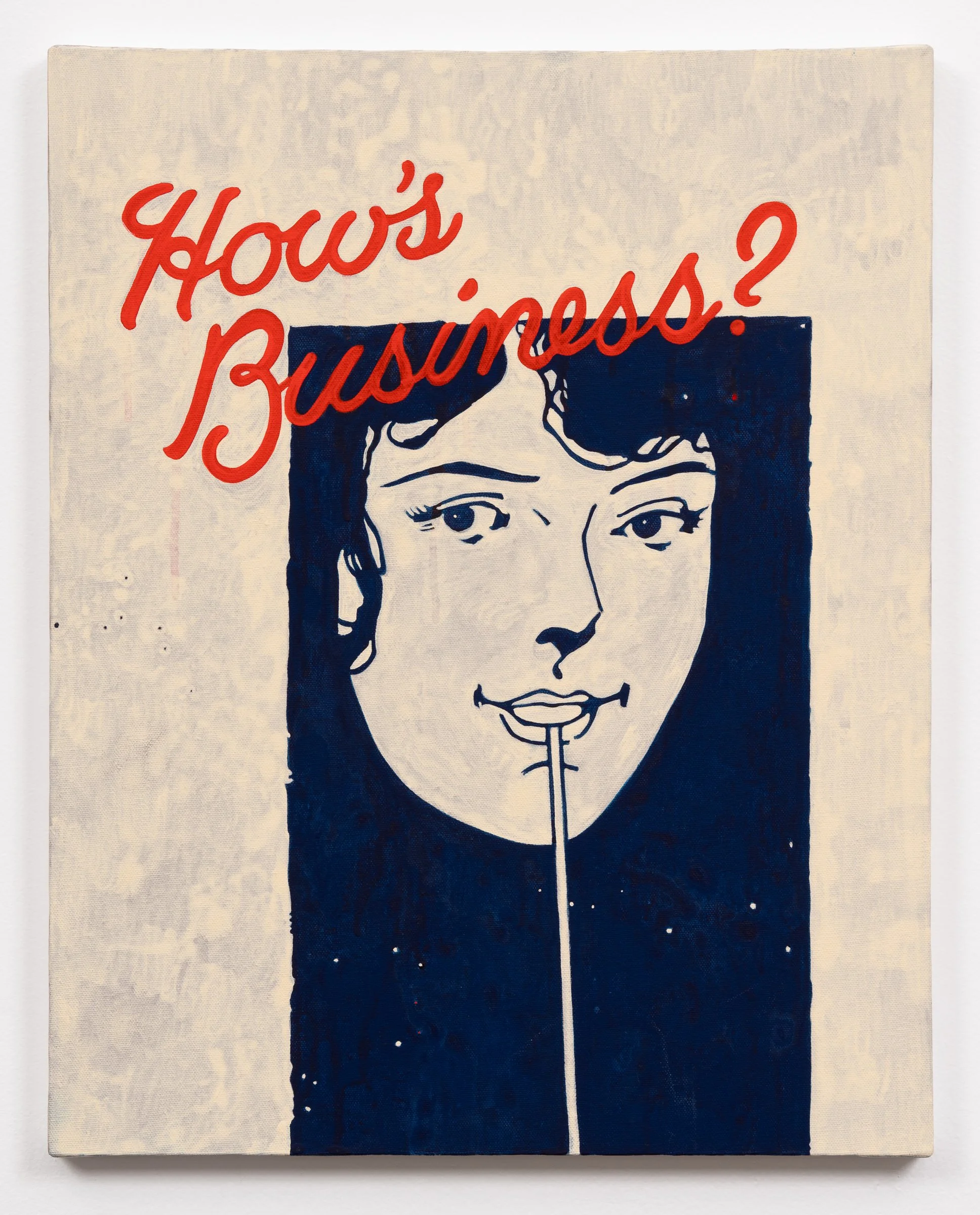

Kim Kennedy Austin’s How’s Business: 1923-25, gesso, acrylic, and Flashe vinyl on canvas. Photo by Blaine Campbell

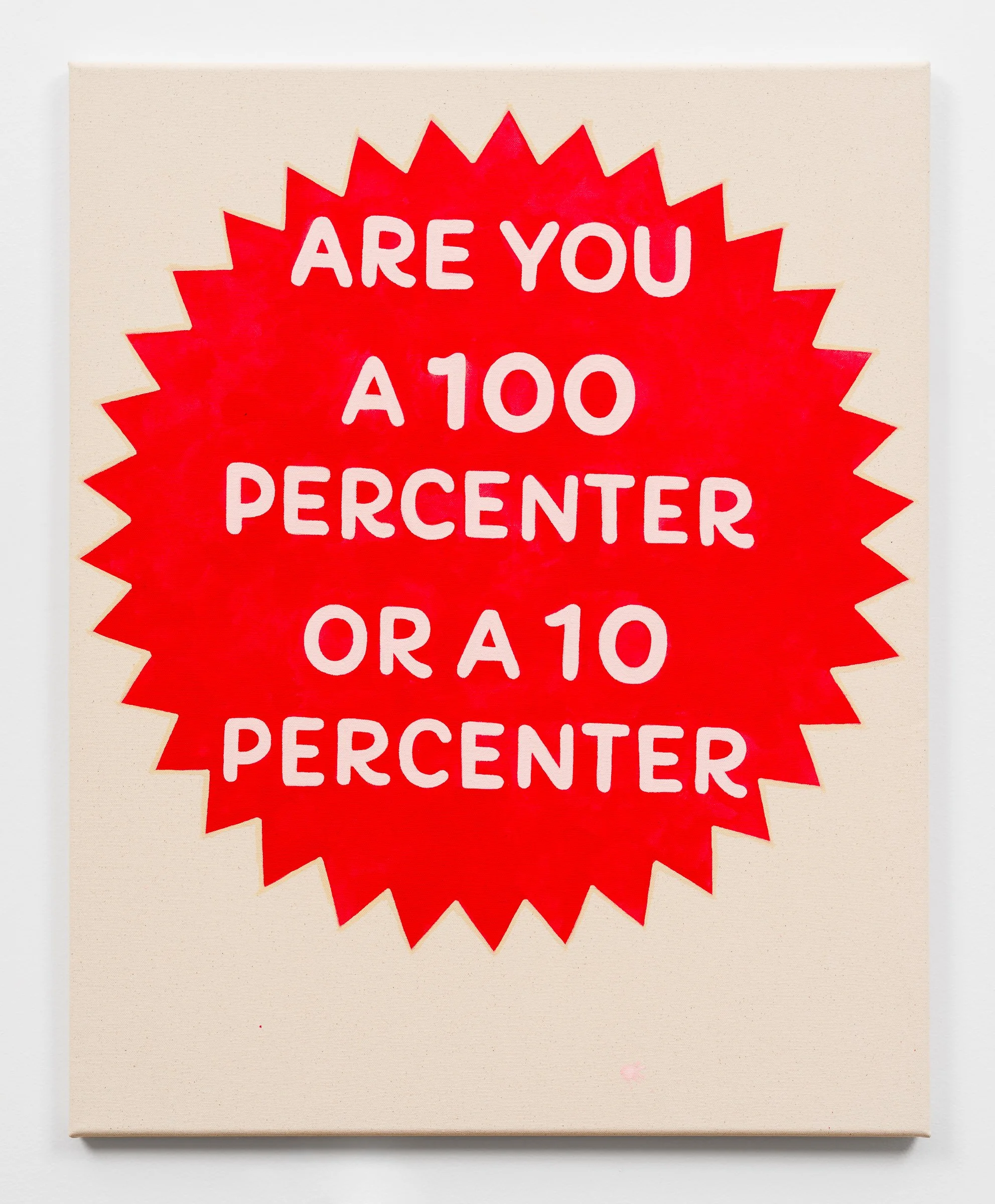

Kim Kennedy Austin’s Are You A 100 Percenter, coloured pencil, acrylic, and gesso on canvas. Photo by Blaine Campbell

Burnaby Art Gallery presents Kim Kennedy Austin: Booster Club to April 20

HE DIED IN 1951, but Sinclair Lewis is nonetheless having a moment right now.

Consider the plot of Lewis’s 1935 novel It Can’t Happen Here, in which a populist politician gets elected President of the United States after whipping up fear while appealing to nationalism and promising to make America great again. Once in power, Berzelius “Buzz” Windrip reveals his true fascistic agenda and sets about dismantling the civil liberties of women and minorities.

Sound familiar? It certainly does to pundits from the New York Times, Salon, the Guardian, Slate, and the Washington Post, all of whom have explicitly noted parallels between Windrip and the current occupant of the Oval Office.

Vancouver-based artist Kim Kennedy Austin also sees a great deal of current-day relevance in Lewis’s work. In particular, she cites the 1922 novel Babbitt—which she describes as a “sort of satirical analysis of middle-class American culture”—and 1927’s Elmer Gantry.

“He was speaking in a more poetic, coherent way to things that I had been thinking about in previous exhibitions and bodies of work that I had done,” Austin tells Stir in a telephone interview.

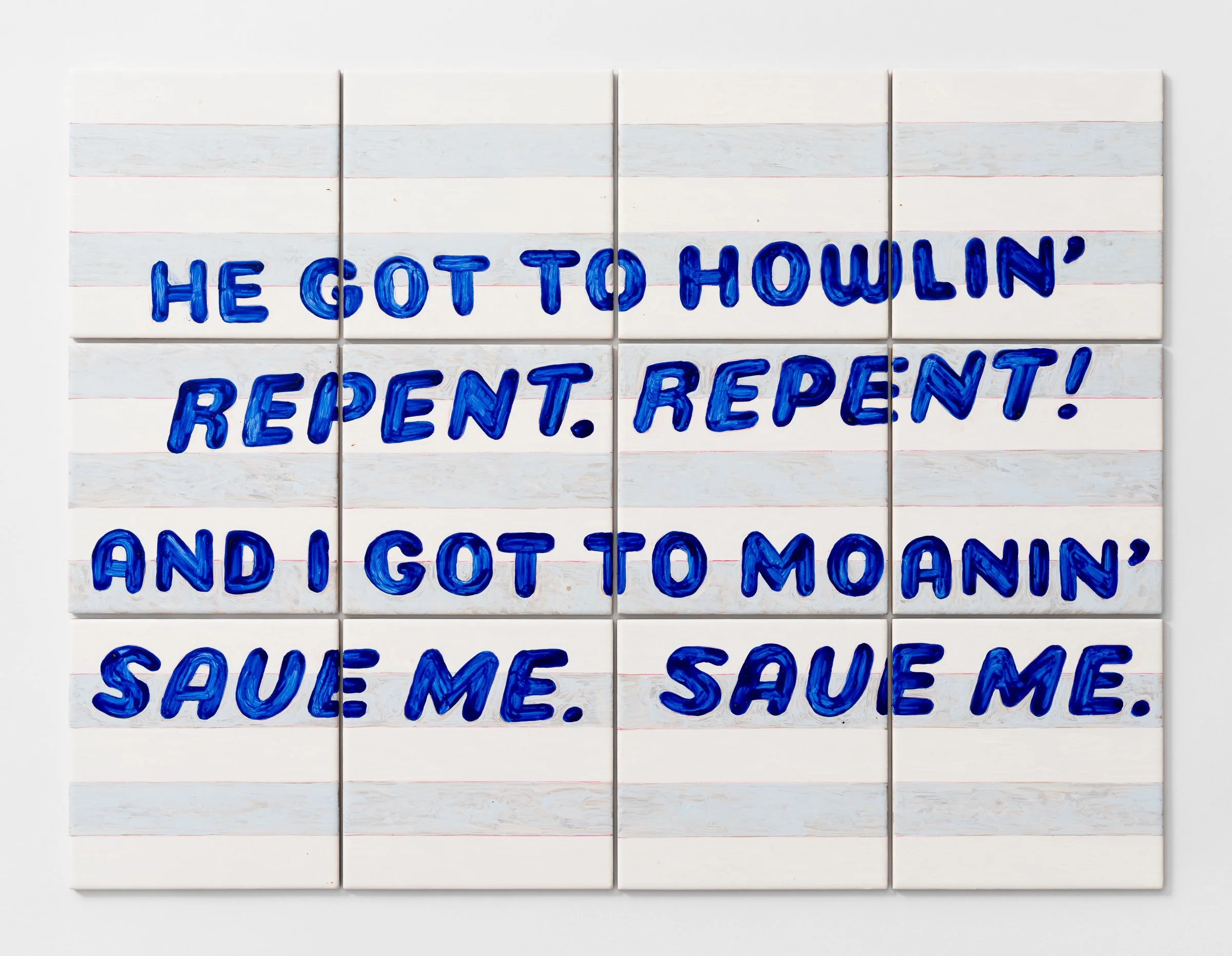

For her new Burnaby Art Gallery exhibition, Booster Club, Austin took much inspiration from Lewis’s novels. The show is divided up into three “chapters”; the first, titled Chamber of Commerce, references Babbitt, while the second, House of Refuge and Industry, draws from Elmer Gantry.

“One is about the business of religion and the other is about the religion of business, and those things are kind of two sides of the same coin,” Austin says.

Kim Kennedy Austin’s Repent. Repent., porcelain paint on ceramic tile. Photo by Blaine Campbell

Combining everyday supplies from hobby and dollar stores, Austin recontextualizes selected illustrations, line drawings, and texts drawn from 20th-century print media to contrast the marketing and portrayal of an idyllic life with what curators Jennifer Cane and Emily Dundas Oke describe as “the alienating realities of production, expansion, and increasing social stratification”.

In an essay to be published in April, Cane and Dundas Oke write that “Austin prompts us to consider how faith, consumerism, and boosterism have collaborated in the construction of these false promises. Like faith asking us not to question whether the church has our best interests in mind, boosterism similarly asks us to believe that the few with power and wealth—and the systems of commerce that they uphold—act in the best interests of our institutions and towns.”

Austin notes that gallery visitors will not have to read Babbitt to grasp the intentions behind her work. “The theme seems really very current,” she says, “and the kind of things we complain about every day, like ‘Why is this real estate agent living in this city, and the only thing he cares about is a bigger, better prefab house in a suburb?’ Everything is about artifice and not about quality. It’s about having the biggest car and the biggest house, and the trappings of being middle class.”

Austin’s approach to creating her work is itself a study in contrasts. While she uses the vocabulary of popular culture and advertising—and, as in the third part of this exhibition, Futurecorp©, science-fiction movies of the 1980s and ’90s—she takes a distinctly crafty approach.

“On the one hand I’m using mass-produced craft materials that I’m picking up by walking into a Michaels or a Canadian Tire or a dollar store, but on the other hand I’m pretty low-tech with how I approach materials,” Austin says. “Whether I’m making a drawing or a painting or sewing with yarn or placing beads, it’s all very handmade, slow, and laborious. So I’m combining those two things. I’m not afraid to embrace my upbringing as a child of a plastic generation, but I still kind of feel the need to take time and have my own physical touch, my own hand involved in each artwork. I’m not gonna get it fabricated if I can make it myself, even if it takes longer.”

Austin acknowledges that the people depicted in these works fall into a very narrow archetype, which she describes as “white, middle-class, able-bodied, fairly slim”, which is a reflection of the early-20th-century magazines from which many of the images are sourced.

“I’m always a bit cautious about adding on to that by not showing anything diverse, but I think it’s really important to remember that that wasn’t shown,” she says. “These magazines were trying to promote a very specific viewpoint of what a successful, upwardly mobile person looked like.”

Kim Kennedy Austin’s The Professionals (1977-1983), yarn on plastic canvas. Photo by Blaine Campbell

The types of films referenced in the Futurecorp© chapter also presented a very specific viewpoint, albeit a much darker one. Dystopian entertainments like Total Recall and The Matrix tended to present visions of, as Cane and Dundas Oke put it, “a world dominated by corporate and political powers that have merged in a swarm of incarceration and forced labour”.

“There are moments where we might ask how close we are to this reality, sensing parallels to our current moment through the normalization of outrageous political theatre and trends towards conformity, cruelty, and subjugation,” the curators write. “But through the vantage of Booster Club, this new world is already familiar, and arrives whistling, well-dressed, and bearing a brilliantly white smile.”

In other words, it’s precisely the sort of world that Lewis was trying to warn us about.

“It’s such a weird time, politically,” Austin observes, “and maybe it’s an interesting time, with this exhibition, to think about how we’ve come to a place where a caricature—a clown, a buffoon—has become a world leader, and how we got there, and what we’re admiring and what we’re purchasing, and how that puts a person like that in power.” ![]()