Stir Q&A: Sri Lankan-born, Toronto-based visual artist Rajni Perera sounds off on science fiction, mutation, and past lives

Surrey Art Gallery is launching its 50th anniversary with the touring exhibition Rajni Perera: Futures

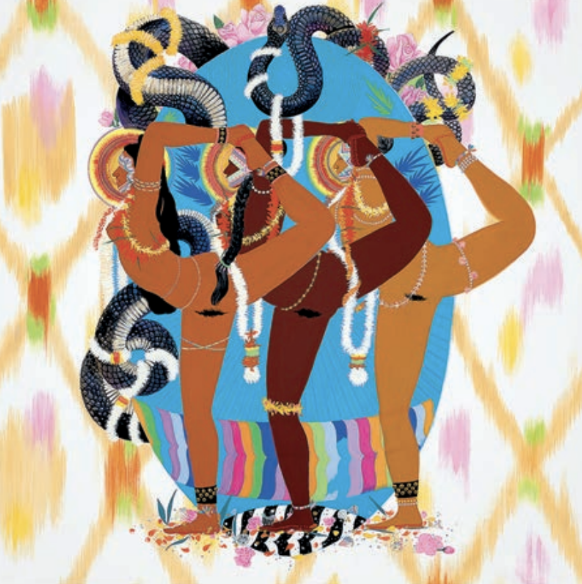

Rajni Perera, I take a journey, you take a journey, we take a journey together, 2020. Courtesy of Paul and Mary Dailey Desmarais III. Photo courtesy of the artist and Patel Brown

Surrey Art Gallery presents Rajni Perera: Futures to March 16; Perera will be at the gallery for a tour and conversation with independent curator and writer Negarra A. Kudumu on March 1 from 2 pm to 4 pm

RAJNI PERERA LOVES science and science fiction. The Sri Lankan-born, Toronto-based visual artist has read works by Isaac Asimov and Theodore Sturgeon and enjoys magazines like Nautilus and Scientific American.

Having moved to Ontario via Buffalo from her home country at age eight, Perera sees parallels between science and the immigrant experience, and she draws on both in her vivid, varied artworks.

Surrey Art Gallery is launching its 50th anniversary with the touring exhibition Rajni Perera: Futures until March 16. Organized and circulated by the McMichael Canadian Art Collection and curated by Sarah Milroy, Futures includes nearly 30 works from various stages of the artist’s career, spanning painting, sculpture, and photography. (Surrey Art Gallery is the only West Coast stop on the tour.)

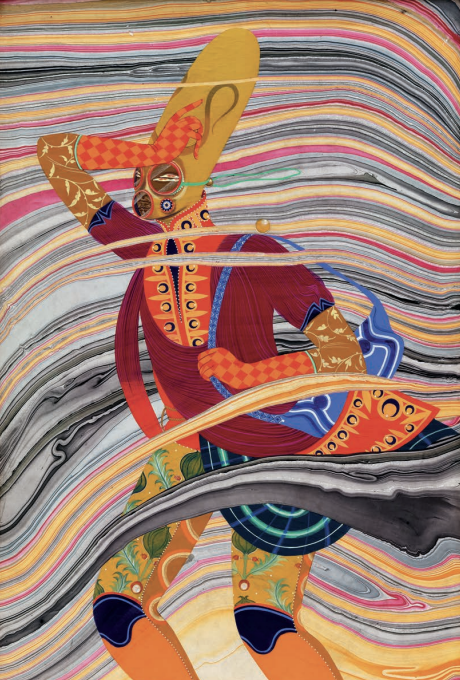

In the exhibition, Perera conveys her vision of imagined futures in which mutated subjects adapt to exist in dystopian environments through perseverance and strength. Perera is influenced by the artistic traditions of Sri Lanka while Indian miniature painting, medieval armour, and South Asian textiles also factor into her work. She explores feminist and diasporic narratives while contemplating survival amid the climate crisis.

Stir connected with Perera to find out more.

Rajni Perera, Natarajasana (Dancer’s Pose), 2013. Photo courtesy of the artist and Patel Brown

How did art first enter your life?

I’ve been drawing and painting since I was a toddler. The first art I ever saw was animation on television and an oil painting of a nondescript American-style cottage in my parents’ house in Colombo [Sri Lanka’s executive and judicial capital city]. I loved the natural world so that’s what I first started to draw and was inspired by my father’s friends documenting new species for various zoological societies around Sri Lanka. A side note is that both my parents are creative people but never considered it as a career.

What is it about making art that appeals to you?

In my past life I was an artist and I’ll be born again as one. I don’t think it’s so much about something that appeals to me as much as being part of a cycle of inheritance, and it’s simply in me to make. Being an artist is actually very, very difficult, and it’s not a profession for people who’d like to feel delighted every day. I do have fun, though, and I enjoy the risk and research involved in my fate.

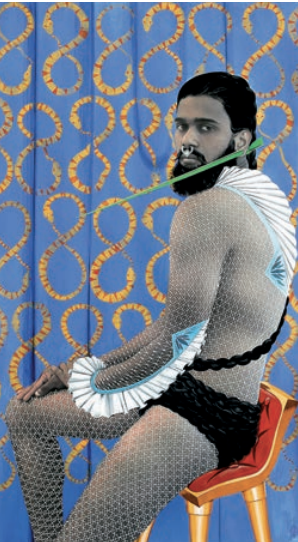

Rajni Perera, Nate, 2017. Photo courtesy of the artist and Patel Brown

What themes do you wish to convey through your art?

My work continues many, many stories about resilience, change, the brilliance of the oppressed, the innovation of the displaced, clothing as technology, evolution versus mutation, portals, monsters, icons, and the way we create and present knowledge.

Why is it important to you to depict the brown body in your work?

Well, if we here in North America want to believe in the remote possibility of fair representation, then let’s consider the fact that people of colour are actually the great majority of the Earth’s population. That’s all I really want to say about it. I’m not making “identity-based work”; what I make only ends up being spoken about like that in Europe and the colonies, such as Canada.

Rajni Perera, Plane Bend, 2020. Photo courtesy the artist and Patel Brown

What do you enjoy about science fiction?

So many things! For me it’s always been this great medium that lets us have very difficult conversations in imaginative and slightly buffered ways. What attracted me at first, though, was its brilliantly conceived artwork, and the way that authors used it to world-build radically, without the restrictions of contemporary ideology or even physics itself. And I also have always enjoyed the feeling of it, the adventure of it.

What are some of the related book titles you have read?

At the SAG you can actually find a reading nook with a list of works there. They asked me to provide a list and it’s there to enjoy. Here it is: The Last Human, Yale Press; Entangled Life by Merlin Sheldrake (the illustrated one is better); Fungarium; Survival Takes A Wild Imagination by Fariha Róisín; Future Diasporas by Alycia Shanika; Generation Dread by Britt Wray; The Science Fiction Bestiary edited by Robert Silverberg; The Left Hand of Darkness by Ursula K. Le Guin; and Parable of the Sower by Octavia Butler.

Where do you find parallels between science fiction and the immigrant experience?

Immigrants are the citizens of the future, which is why they have always been at the centre of my Traveller universe. I see space travel as a good metaphor for the trials of immigration and the innovation, tradition, and social change it sparks. I happen to come from this community and noticed from my love of sci-fi that there were very few POC in visual depictions of it, and the colonization of its ideology and aesthetics, so I started to think about how I could confront that as well using this series.

Rajni Perera, Storm, 2020. Photo courtesy of the artist and Patel Brown

Where does your fascination with mutation come from?

I have a series called “Phylogeny” (the study of evolutionary biology in response to changing biomes) that explores the idea of mutation as a revolutionary response of the living body as opposed to the possibility of death. Something I’m really taken aback by is the way that different beings wrap themselves around their circumstances and take up different shapes, and at times it’s by ingesting their environment. In the series I explore it literally and surreally but in Traveller it’s looked at spiritually, culturally, and societally as well. I also find the difference between mutation and evolution to be interesting, as one could say that within the Anthropocene age, mutation will be the only evolution we have the timescale to afford.

What can you tell us about I take a journey, you take a journey, we take a journey together and Plane Bend?

I take a journey, you take a journey, we take a journey together is my third pollution mask after the first three small ones made for the Traveller show. I started making pollution wear after going to Delhi and seeing different versions of decorated and opulent N95 fume and particulate masks. I wanted to push it all the way and make full headpieces that are functional and built on top of preexisting dead-stock masks.

Plane Bend is from the Lightwork series investigating some lighting and sculpture with Kate MacNeill of Concord Custom Lighting here in Toronto. Kate is super brilliant and a great problem solver, and we collaborated on that as well as other brass-plated light pieces with simple materials that allude to some physics and astronomical phenomena. In this case it’s a very distorted orbit as well as a pearl on a tongue. ![]()