Stitched: Merging Photography and Textile Practices pushes lens-based art into multidimensional new realms

New Capture Photography Festival exhibition at the Gordon Smith Gallery of Canadian Art moves the form through beadwork, weaving, handstitching, and more

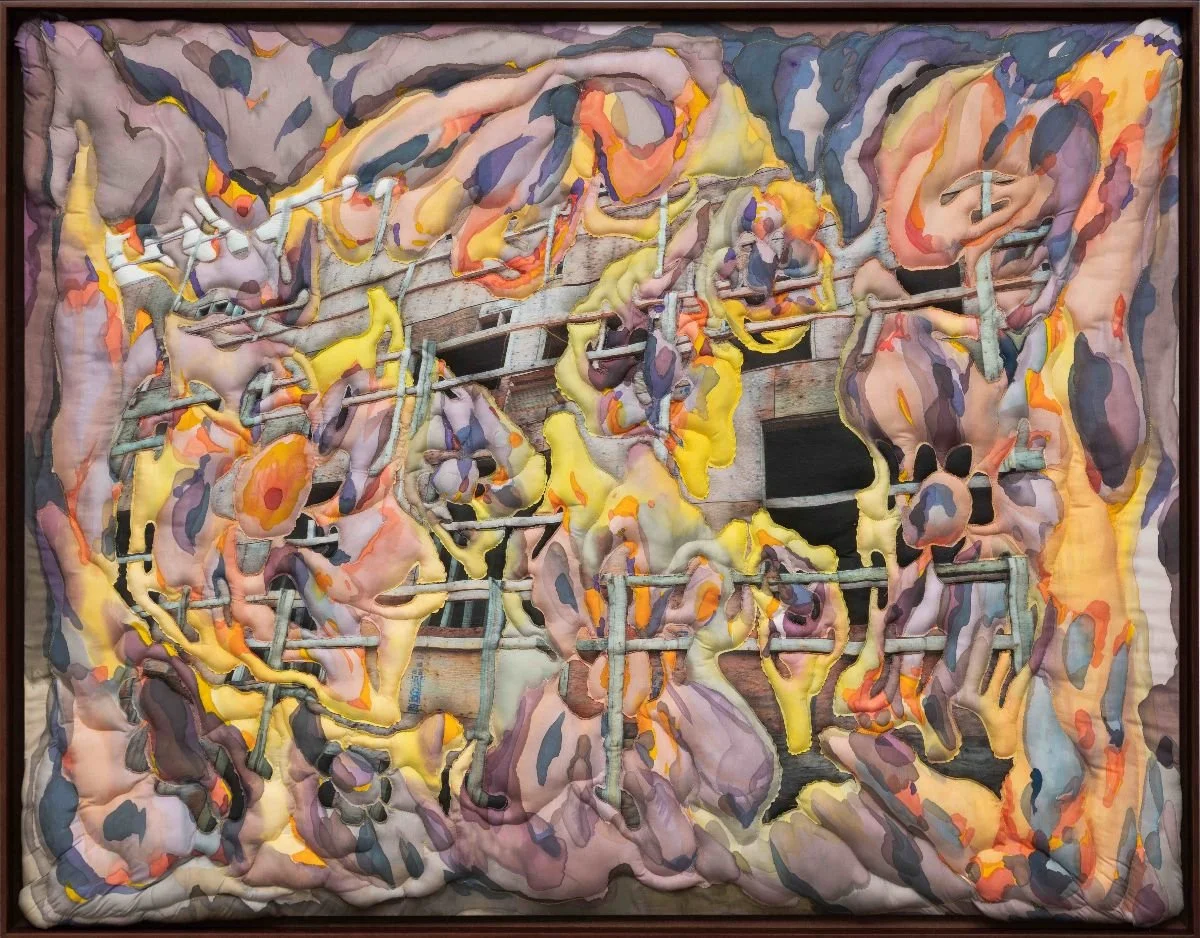

Maya Beaudry’s Lattice, 2024, digital pigment print on cotton, acrylic ink. Courtesy of the artist and Towards Gallery

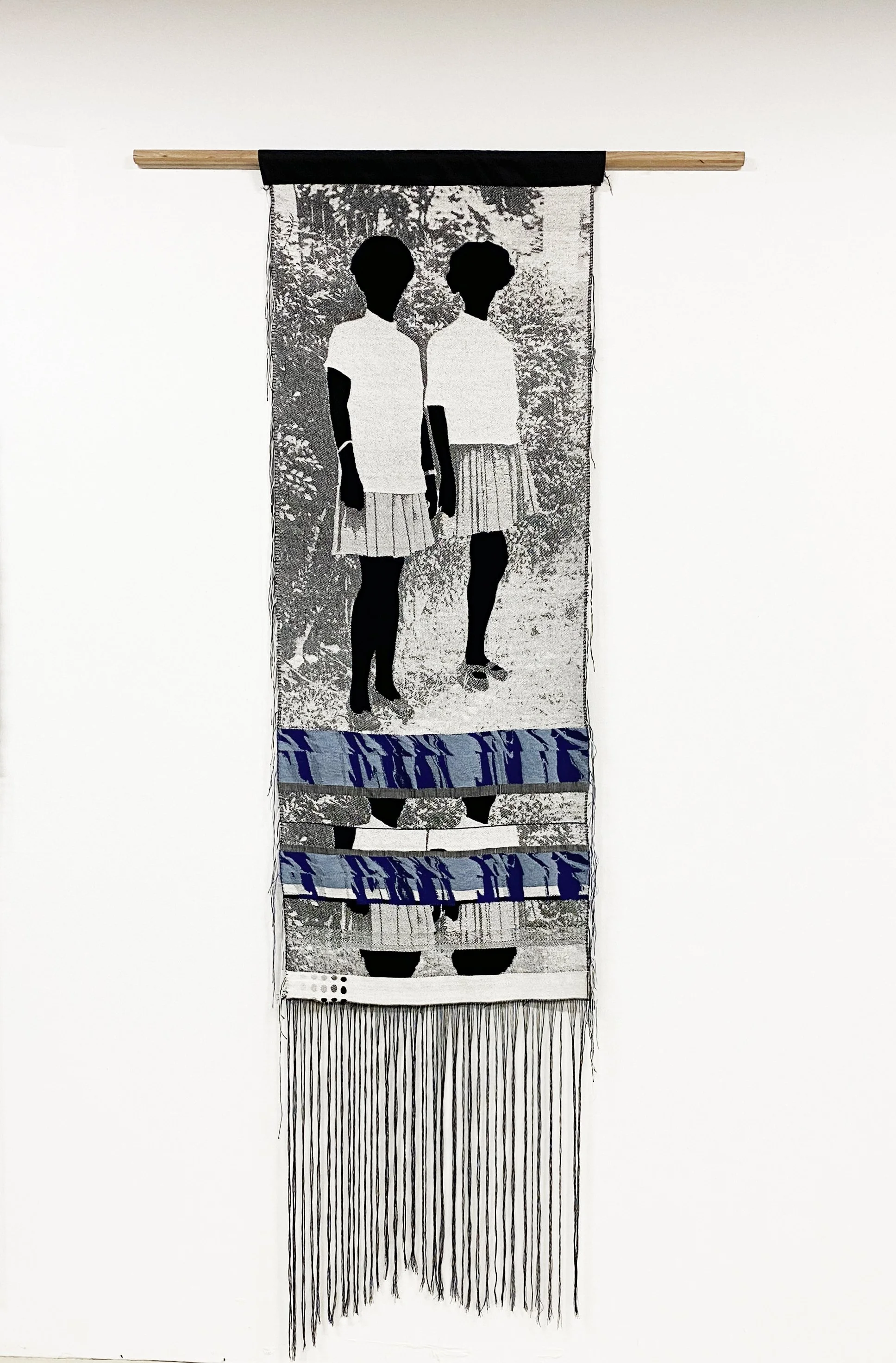

Michaëlle Sergile’s Ombre Portrait (Zanni), from the “Ombre Portrait” series, 2024, cotton, two-shuttle jacquard loom. Courtesy of the artist and Galerie Hugues Charbonneau

Stitched: Merging Photography and Textile Practices is at the Gordon Smith Gallery of Canadian Art to June 21

SO MUCH OF WHAT we experience of photography today is fleeting—viewed in an instant on a two-by-five-inch screen before we scroll on to something else.

Capture Photography Festival executive director and chief curator Emmy Lee Wall was consciously pushing against that with the new feature exhibition Stitched: Merging Photography and Textile Practices.

Integrating photography with textile craft in sophisticated and unexpected ways, the show not only invites slow looking, but, as Wall points out, “it evokes touch and physicality” at every turn. (A video work, Simranpreet Kaur Anand’s mukti maal kanik laal heera man ranjan kee maaiaa, even evokes the sound of fabric and sequins being spread by fingers.) Many of the pieces integrate traditional loom weaving and hand-stitching, and move lens-based work into new realms of texture and three-dimensionality. When was the last time you went to a photo exhibition and there was meticulous beading, jacquard weaving, and three-dimensional hanging installations?

“A lot of photo artists have moved away from putting a photo in a frame and hanging it on the wall, and this exhibition really shows how photographers are expanding the definition of photograph,” Wall remarks, surveying the new show at the Gordon Smith Gallery of Canadian Art in North Van.

Co-curated by Wall and Capture assistant curator Chelsea Yuill, the exhibition has been years in the making and is the largest textile-based show that Capture has ever staged. Nine artists from across the country—eight of them women—integrate the once male-dominated practice of photography with the traditional female work of sewing and weaving with fascinating results that demand slow looking, from far away and up-close.

Take Cree and Métis artist Michelle Sound’s powerful Mother Land, in which she has used thread, beads, ribbon, quills, and caribou tufting to stitch close the gashes she’s cut into large images, such as an archival photo of herself and her mother, or another of a landscape. The work speaks to the wounds of colonialism.

There’s a joy to the meticulous repair and resistance being enacted here: the multicoloured beads, the pink bric-a-brac, the jaunty pompoms. “Despite this colourful repair, the holes are still there—they don’t come together and you're unable to fully merge the gap,” Wall points out.

Michelle Sound’s Mother Land, 2024, monochrome print on paper, embroidery thread, rikrak, seed beads, caribou hair tufting, ribbon. Courtesy of the artist and Ceremonial/Art

Elsewhere, works from Quebec artist Michaëlle Sergile’s “Ombre Portrait” (“Shadow Portrait”) series draw on archival family images from her parents’ generation in Haiti, reimagining them in intricate two-shuttle jacquard loom weaving. The photos speak to family bonds but also to missing histories, the faces and bodies rendered as black, faceless silhouettes: “These immense voids do not serve to erase their identities but rather to represent the vastness of stories and the numerous layers of memories,” the artist has written about the works.

The care that Sergile has taken in making the images is evident; it can take weeks to thread the large looms Sergile uses in the process. But the weaving also carries rich metaphorical meaning, in “the bringing together of cultures and the multiple threads that come together to make a culture or to make an identity,” as Wall says. Each hanging panel frays and fringes at the bottom—identities yet to be woven, stories fraying through time or perhaps waiting to be told.

Much of the work marks a departure from photography’s traditional documentary role—its association with “truth”. “These artists have really flipped that on its head,” Wall explains. “They’re asking people to embrace subjectivity and uncertainty.”

In the case of veteran artist Barbara Astman, what looks like geometric abstract art or quilted tapestry reveals itself upon close looking to be a patchwork of women in advertisements. (She’s actually transferred newspaper images onto lengths of clear packing tape and then woven them together.)

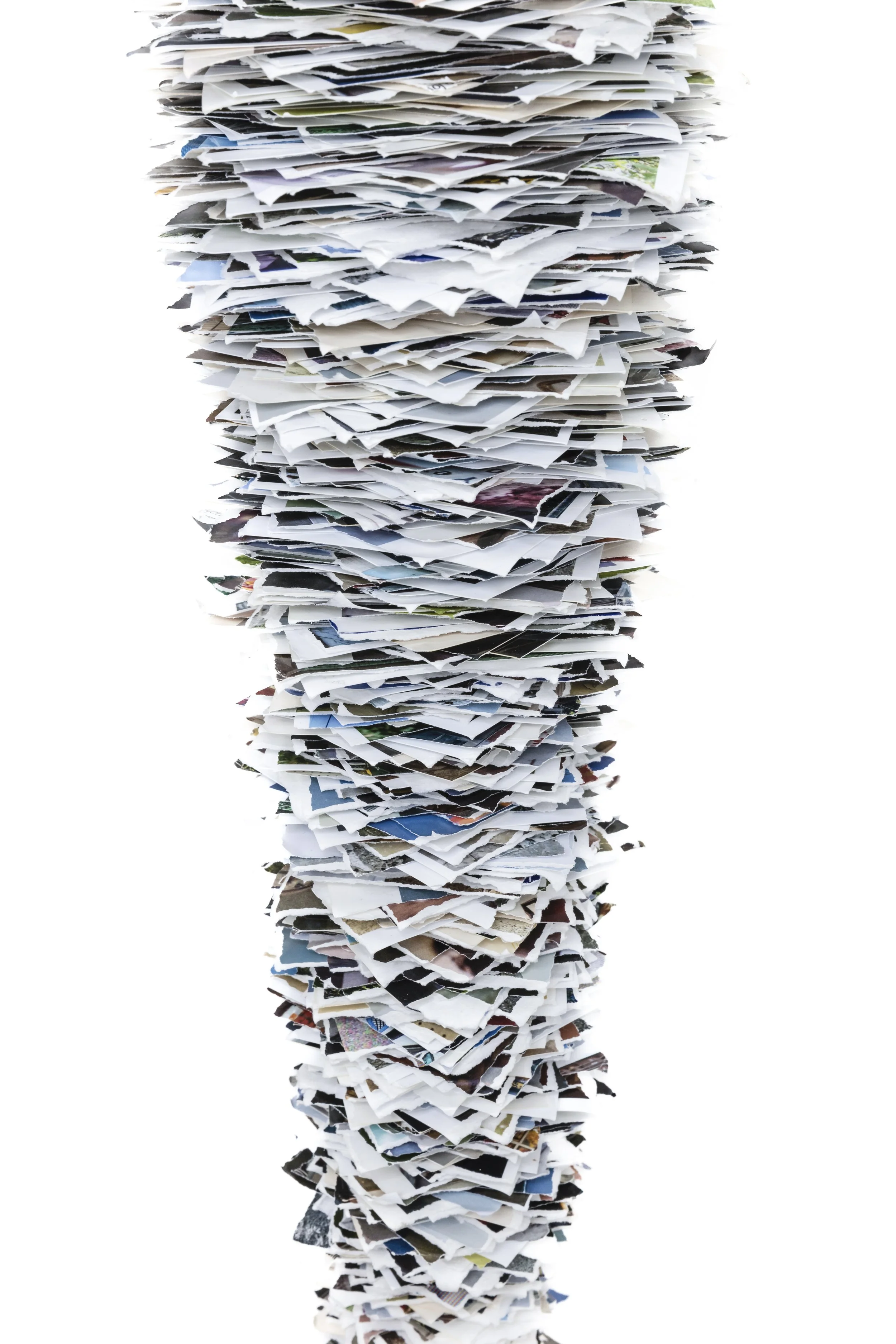

Jayce Salloum’s nest (detail), 2016, torn photographs. Courtesy of the artist, Mónica Reyes Gallery, and MKG127 Gallery

From a distance, Vancouver textile artist Maya Beaudry’s Lattice looks like a colourful quilt of swirling organic forms. Look closer and you start to see flames licking up. Move closer yet, and you see them engulfing a photo image of a wood building—a sly nod to the cycle of deconstruction and construction in her real-estate-enflamed hometown.

And you won’t be able to discern the precise content of the carefully ripped and piled photographs that make up Jayce Salloum’s strangely transfixing hanging installation: they’re images from his own travels, but they’re tightly stacked so that they remain obscured. The undulating, ropelike sculptures can be read as a metaphor for memory, for keeping the personal private. “Or it could be read to symbolize the accumulating of all these images on our phones,” suggests Wall. “And how do we accumulate the weight of that?”

Dana Claxton’s Headdress–Connie, from the “Headdress” series, 2018, LED firebox with trans mounted chromogenic transparency. Courtesy of the artist and Art Gallery of Greater Victoria

In fact, there is only one artist whose work falls into the category of pure photography—but even here, boundaries and definitions are being pushed. Wall identifies Dana Claxton’s Headdress–Connie and Headdress—Jeneen from the Audain Prize-winning artist’s famous “Headdress” series as the “anchor” of the show.

As large, glowing LED fireboxes, they’re not quite photos hanging on a wall in frames, but they provide a spectacular jumping-off point for Stitched—upending the idea of the photo portrait by obscuring the subjects’ faces with elaborate Indigenous beadwork. Jeneen’s spans three generations of beading by the Vuntut Gwitchin First Nation; Connie’s features her own designs. Here, women are adorned with cultural belongings, as cultural carriers. As with so much else in the show, time becomes fluid, with age-old handiwork tradition filtered through a contemporary lens—and it takes slow looking to take in the explosion of vibrant details.

“They put a female Indigenous creator behind the lens and disrupt the colonial view,” Wall says. “So it’s an amazing way to start to think about how textile and clothing can be conveyed through photography.” ![]()