Deborah Colker takes viewers into Brazil's Capibaribe River region with Dog Without Feathers

Mud-soaked dancers bring to life a place where humans both rely on and destroy a waterway

Humans caked in mud toil in front of projections of cracked river beds in Dog Without Feathers. Photo by CAFI

DanceHouse streams Companhia de Dança Deborah Colker’s Dog Without Feathers from September 29 to October 11 via Digidance.

IT’S 9 PM in Rio de Janeiro, and Brazilian dance legend Deborah Colker is still in the middle of rehearsals for her first live stage work since the pandemic. Called Cura, it’s a celebratory multimedia ode to healing that draws on all the cultures of the world—one of her signature, grand-scale visions.

But far from looking tired on a Zoom call with Stir, she radiates unfiltered energy over the screen, repeatedly hopping to her feet with passion, leaning close into the screen to emphasize her points, and fuelling herself with a small cafezhino, the jet-black coffee that Brazilians love.

Thirty years into a career that has spanned choreographing the 2016 Rio Olympic ceremonies and Cirque du Soleil’s Ovo, Colker is still a fantastic force of nature. That fact will become clear to Vancouverites who watch Companhia de Dança Deborah Colker’s dazzling yet disturbing Dog Without Feathers, streaming this week via DanceHouse.

Choreographer Deborah Colker has created grand visions for everything from Cirque du Soleil to the Rio Summer Olympics. Photo by CAFI

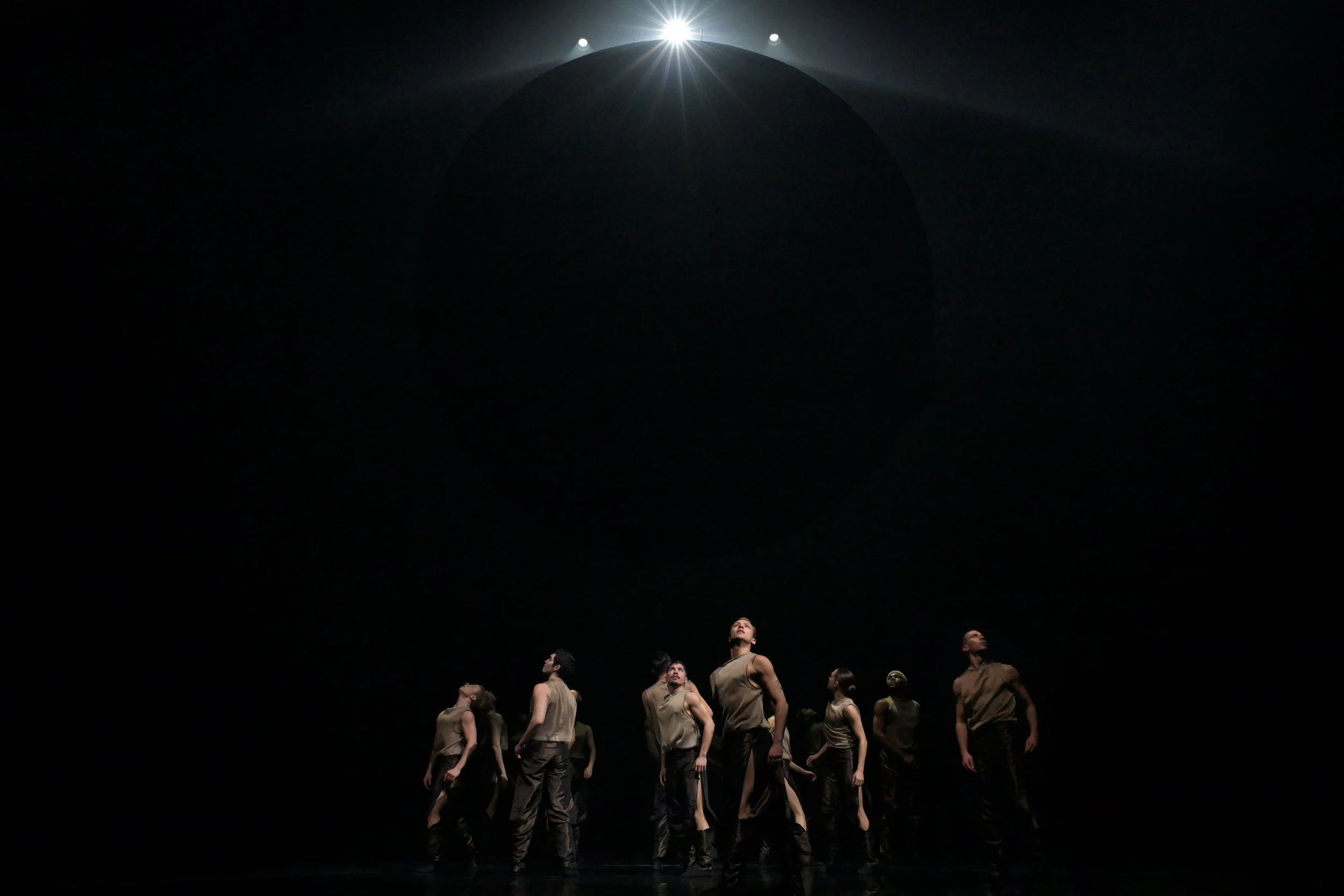

Blending dance, cinema, and poetry, it features 14 dancers caked in mud and dust moving against film projections and photos of parched river beds, shanty towns, and burning crops. It is a vivid cry for both the planet’s ecological doom and its effects on poor working people in the world.

In fact, Dog Without Feathers is based on an intense three-week-long visit that Colker and her troupe took to Brazil’s Northeastern region, following the Capibaribe River to its mouth at the Atlantic, in the city of Recife.

“Dog Without Feathers is a scream—it talks about things that are inconceivable. It’s my indignation!” Colker says, the words pouring out of her. “It’s my fight against discrimination, against disrespect. It’s visceral, it’s primitive! I build a body and movement that is both human and animal—like some kind of a creature. Like a man-crab.

“I wanted to give to the audience that place, with its mangroves and that river and that sun and the sugar cane,” she adds, “that place that is so miserable.”

The piece, debuting here in a film version, is inspired by a 1950 poem by João Cabral of the same name—one that’s heard in voiceover in the work. Seventy-one years later, Colker is struck by how little has changed about the polluted river he describes.

“There are people that live through the river; they work fishing, catching crabs, or planting food near the river but these people are invisible—excluded people, like refugees are or migrants are,” Colker says. “This is happening everywhere around the planet.”

Dog Without Feathers. Photo by CAFI

As for the clay-covered dancers, the imagery draws from the omnipresent mud between the river and the land in the Capibaribe region, Colker says. “The flesh is the soul of these people. It’s the way I could represent their pain,” she explains. “They are part of the river.”

Colker is eager for the world to see Dog Without Feathers, but she’s equally excited to speak about the new direction she’s taking since pandemic lockdown. COVID-19 has hit Brazil with devastating force, and she leaves little ambiguity about whom she blames for that. “We have two viruses in Brazil,” she quips, “the government and COVID. Ignorance is my biggest enemy, and the biggest enemy of humanity.”

Health measures and vaccinations now finally allow her to work with her full crew of dancers unmasked, and she’s finding herself creatively charged.

“With Dog Without Feathers, I was more interested in the physical and the earth and the land, but now it’s song and dance,” she says. of Cura “With Dog Without Feathers, I was inside the river and I was in this dry cracked land; with this performance I need to transcend all that.”

Like it did for so many around the world, the enforced pause of lockdown made her refocus on what’s important, on what she calls “the value of being alive”, and how dance is the perfect vehicle to communicate that.

The idea takes her back to the shores of the Capibaribe, where she would watch Indigenous people dance and sing, despite the hardship. “They know how to make a rhythm, to dance, touch the ground with their feet and claim for all the planet dance,” she says, standing up to emphasize her point before heading back into night rehearsals. “We need to save the planet earth with our bare feet.”