Dumb Instrument Dance explores what it means to rise up with Rebel Grace

Choreographer Ziyian Kwan and friends explore the gentler side of subversion

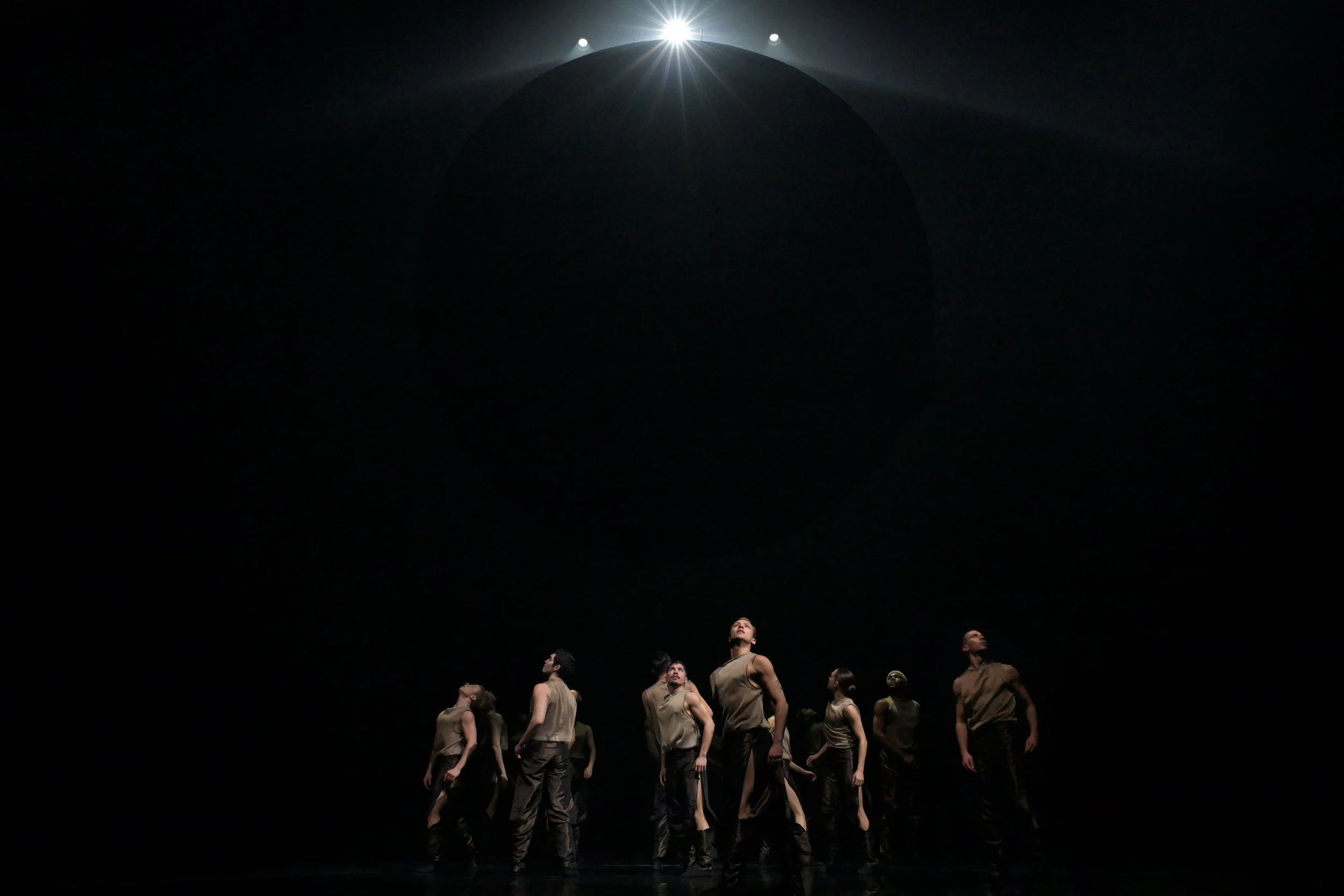

Justin Calvadores and Lisa Gelley Martin in Rebel Grace. Photo by David Cooper

The Dance Centre presents Dumb Instrument Dance’s Rebel Grace from May 12 to 14 at the Scotiabank Dance Centre

REBEL GRACE. At first, the two words feel contradictory, but talk to veteran Vancouver choreographer Ziyian Kwan about her journey over the past two years and they start to feel much less like an oxymoron. In this time of divisions and massive social movements, is there a way to protest and subvert with artistry and care?

It’s something Kwan has been thinking about a lot during the pandemic—and acting on: look no further than the artist’s peaceful dance action near the start of the COVID, when the Chinese Cultural Centre was defaced by anti-Asian racism. That was only beginning: she went on to open an inclusive dance studio called Morrow, staged the whimsical Dreaming of Koi in the Dr. Sun Yat-sen Classical Chinese Garden for Dancing on the Edge, and more. Kwan calls this two-year period one of “maturing and of extreme reinvention” for her.

The phrase Rebel Grace forms the title for the Dumb Instrument Dance artistic director’s latest ensemble work for a group of diverse performers—Justin Calvadores, Lisa Mariko Gelley, Juolin Lee, Andrea Nann, and Rianne Svelnis, along with live musicians Roxanne Nesbitt and E. Kage. It’s no accident that the performers are women or nonbinary, with all but one a person of colour. And the two key words have driven a lot of the ideas behind Kwan’s choreography, during her stint as the Dance Centre’s artist in residence.

Ziyian Kwan in Rebel Grace. Photo by David Cooper

“It’s wanting to say ‘no’ to all the things I feel are oppressive, and wanting to say ‘yes’ to the things I feel strongly about in ways that are democratic, that don't do harm,” Kwan explains, speaking to Stir on a break from rehearsals. “For instance, it’s not just saying ‘no’ to misogyny, but ‘yes’ to the power of women in the world. Also, in offering rebellion, I wanted to offer alternative ways of responding to things that are about evoking something positive and poetic, as opposed to just complaining.

“There’s so much going on in the world to rebel against and I think it's such an incredible privilege we have, to be able to speak out. So to do it responsibly is really important to me,” Kwan adds. “It’s also thinking about things like rupture, and what happens when there's conflict and how to move through it. How not to attack but give voice.”

Giving voice has been a huge part of her process with the dancers—who have been collaborating on this, her biggest piece since the pandemic. Their words mix in some of the piece’s spoken text, along with Kwan’s own, sometimes cheeky, poetry. (In one section, she puts a twist on “A Chorus Line”: “One, step towards equation, every step we take/ One redemptive altercation, every voice we stake/ Just one No, and suddenly echoes of YES shine through.”)

Look for Kwan to play with props, a signature in most of her past works, which have found dancers wielding everything from giant inflatable balls to suitcases over the years. Here, she “repurposes” thrift-store-find furnishings.

“It was part of my creative process: I took normal furniture objects and thought, ‘How can I subvert a normal object and have it be used for something else?’” says Kwan. “For instance, I took a table that has more of a colonial appearance, and said, ‘How could I subvert that and use it in different ways?’” In another instance, she painted a vintage Shoji screen.

In the end, the piece, which the choreographer describes as eight vignettes, reaffirms Kwan’s belief that small artistic acts can have big ripple effects. That they can be rebellious yet graceful acts of change.

Adds the artist: “It’s gently transgressive, but also celebratory in the ways that it’s possible to be proud of who we are, with all our quirks and vulnerabilities in this time.”