Bill Reid Gallery and Jewish Museum & Archives of BC explore decades-old potlatch recordings in Keeping the Song Alive

The mixed-media exhibition highlights work by late ethnomusicologist Ida Halpern and Kwakwaka'wakw Chiefs Billy Assu and Mungo Martin to document hundreds of sacred, traditional songs

Ida Halpern, right, with Chief Billy Assu and his wife. Image J-00562 courtesy of the Royal B.C. Museum and Archives

Bill Reid Gallery of Northwest Coast Art in partnership with the Jewish Museum & Archives of BC presents Keeping the Song Alive until March 19, 2023; a free opening celebration takes place November 5 from 1 to 4 pm

FOR KWAKWAKA’WAKW PEOPLES, songs are a vital part of their culture, a cornerstone of ceremonies, identity, and lineage. During the federal government’s potlach ban, which lasted from 1884 to 1951, singing, along with other traditional practices, was forbidden. At risk of being arrested, some bold chiefs held potlaches underground. And one brave non-Indigenous woman connected with two of them to help save their songs.

Late ethnomusicologist Ida Halpern and the late Kwakwaka’wakw Chiefs Billy Assu and Mungo Martin worked together over a period of decades to document hundreds of sacred and traditional songs that otherwise would have been lost forever due to colonization. Late in her life, in the 1980s, Halpern donated her recordings to the BC Archives. It’s a story that hasn’t been widely told, until now: Keeping the Song Alive is a new exhibition that shines a light on this remarkable collaboration and its enduring legacy.

Presented by Bill Reid Gallery of Northwest Coast Art in partnership with the Jewish Museum & Archives of BC, the show features Halpern’s recordings from the 1950s of traditional songs fundamental to Kwakwaka’wakw culture. The exhibition also features Halpern’s original audio recorder, records, research notes, and photographs from her work as an ethnomusicologist in Canada following her escape from Nazi Europe in the 1930s. Such historical artifacts are displayed alongside works (including visual art, film, photographs, and more) by contemporary Kwakwaka’wakw artists made in response to the history and meaning of the recordings.

The genesis of Keeping the Song Alive goes back to 2017, when show co-curator Michael Schwartz learned that BC Archives had submitted the Halpern collection for consideration for inscription on the UNESCO International Memory of the World register. The following March, it was inscribed on the newly launched CCUNESCO Canada Memory of the World register. Schwartz reached out to Beth Carter and Cheryl Kaka‘solas Wadhams at the Bill Reid Gallery, and the idea evolved from there.

Halpern fled Vienna with her husband shortly after the Nazi army’s invasion early on in World War II. Through a circuitous series of events, the couple arrived in Vancouver soon after.

“Ida had grown up in the vibrant musical milieu of Vienna, at the time a global hub of art, culture, and ideas, and she’d gone on to pursue a PhD in musicology, studying under pioneers in the field,” Schwartz tells Stir. “Arriving in B.C., she was fascinated by the local Indigenous nations, and in particular their musical traditions. She worked for years to build up trust and was eventually invited by Chief Billy Assu to record him singing and explaining the meaning and significance of his inherited songs. This experience opened the door for subsequent recording sessions with Mungo Martin, Tom Willie, and other chiefs and elders up and down the coast.

“This work transpired within the context of the potlatch ban, when Indigenous people were forbidden by the Canadian government from singing their songs and holding traditional gatherings,” Schwartz adds. “The potlatch is vital for cultural continuity and as a marker of significant lifecycle events like births, comings-of-age, marriages, and deaths. In this way, the potlatch ban was tragically effective in rupturing many Indigenous people’s awareness of their culture and history….It has been a slow and arduous effort by younger generations to revive these traditions in recent years. Archival materials like the Halpern recordings have been helpful, bolstering the memories of old timers, but still some songs, dances, and stories are lost.”

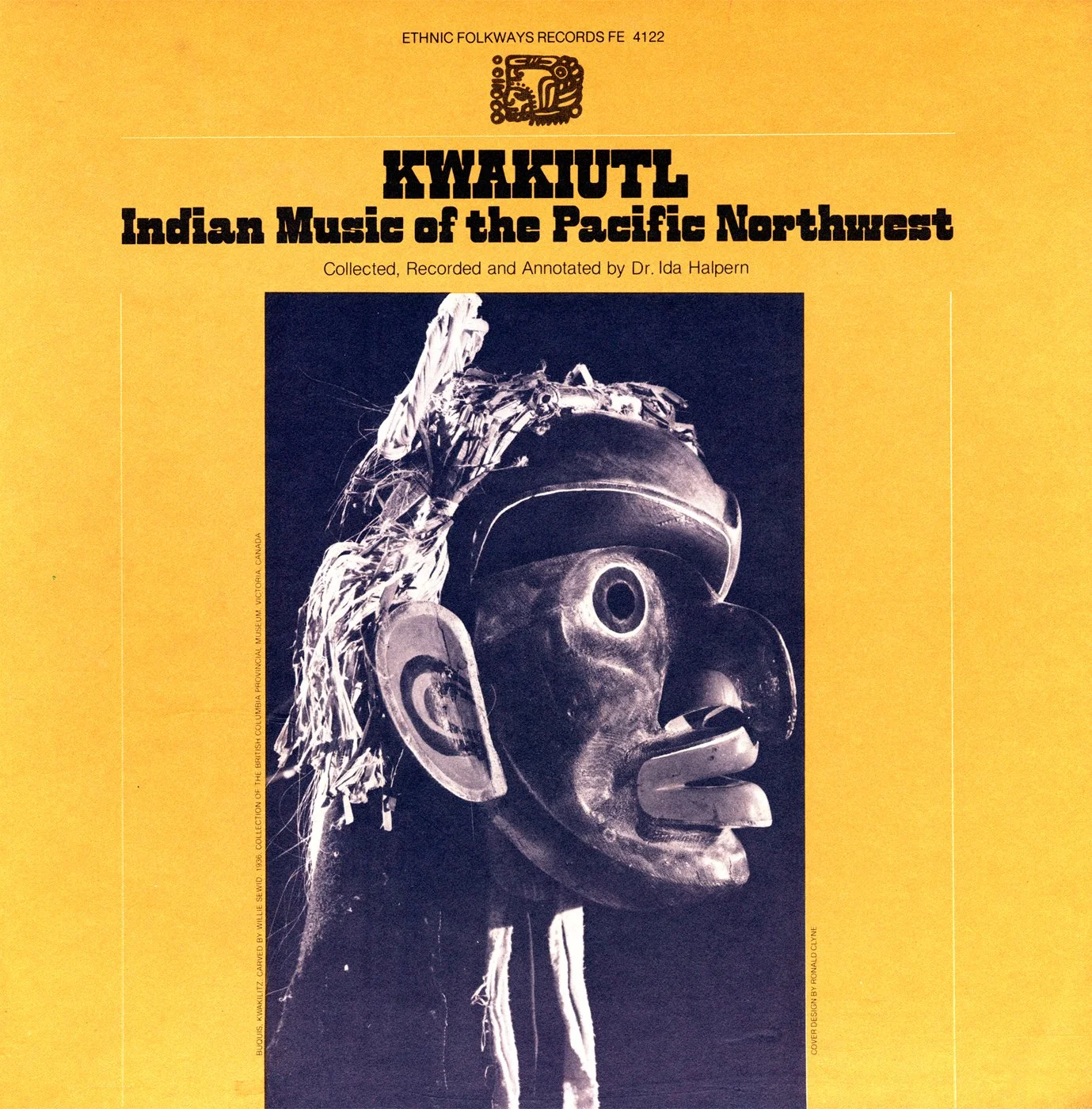

Kwakiutl: Indian Music of the Pacific Northwest, released in 1981 by Folkways Records.

What struck Schwartz upon learning about the work and relationships between Halpern, Assu, and Martin was the sense of trust that was fostered.

“It took time for this trust to develop, but once it was established, they were able to accomplish something significant and lasting,” Schwartz says. “My understanding is that because of Ida’s experience in Europe, the fact that as a Jewish woman she was forced to flee, the chiefs felt a kinship to her.

“During my visit to the Kwakwaka’wakw reserve in Alert Bay, one of the elders conveyed this to me, saying, ‘Well, you understand this,’” Schwartz says, “meaning that I as a Jewish person deeply understand attempts at cultural erasure.”

Keeping the Song Alive co-curator Cheryl Kaka‘solas Wadhams is a member of the ʼNa̱mǥis Nation with connections to the Maʼa̱mtagila, and Mama̱liliḵa̱la Tribes of the Kwakwa̱ka̱ʼwakw Nation. A practising artist with a degree in Aboriginal studies and a diploma in small business, she is an active member of the local Urban Kwakwaka’wakw Dance Group and also works as Bill Reid Gallery’s manager of visitor services and gallery shop. Wadhams is a relatively new Kwak’wala language learner who recently participated in UBC’s First Nations Endangered Language Program.

Wadhams had first learned of the recordings many years ago through her involvement with the Urban Kwakwaka’wakw Dance Group. Hearing them helped her on her own journey of discovering more about her background and culture, which she knew very little about growing up.

“All through elementary and high school, I didn’t know about this history,” Wadhams says in a phone interview with Stir. “These recordings helped with learning about who I am and where I come from.

“It is really important to me to learn our language,” she says. “I hope that people can take away the knowledge of those recordings. For people who are ready to take that step to learn our culture, they might spark that interest. This exhibition can bring our community together, bring our people together. As a Jewish immigrant fleeing the Holocaust, Ida Halpern understood the impact of cultural erasure.”

Andy Everson, Concealment, 2018 Mixed media. Photo courtesy of the Artist

In addition to Halpern’s recordings, Keeping the Song Alive features Ellipsis, an installation of 137 copper LPs critiquing the ongoing oppression of the Indian Act created by Sonny Assu, the great, great grandson of Chief Billy Assu. Andy Everson’s Concealment merges a kitchen-table tea party with potlatch imagery, recalling a time when his family had to hide their ceremonial traditions. A historic headdress by Chief Robert Harris is displayed adjacent to a ceremonial robe, apron, and headdress by artist and community leader Maxine Matilpi. Some of the works by contemporary artists are on view for the first time.

Films by renowned ‘Na̱mǥis filmmaker Barb Cranmer immerse viewers in the potlatch experience, with songs, dances, and drumming. A series of artist talks, Kwakwaka’wakw dance and drum group performances, and hands-on workshops are forthcoming, while visitors can play a replica potlatch drum log. In 2024, the exhibition will travel to the U’mista Cultural Centre in Alert Bay.

Sonny Assu, Ellipsis, 2012 (detail), Copper LP Forge Project Collection, traditional lands of the Muh-he-con-ne-ok

The exhibition’s run is especially timely, Schwartz says, with its development having taken place during the pandemic against the backdrop of an increase in anti-Semitic acts and anti-Asian racism, the discoveries of unmarked graves at residential schools nationwide, the Trump presidency, and the Black Lives Matter movement.

“In short, it’s been a difficult time for many communities and a time of growing recognition of historic struggles,” Schwartz says. “Tension and promise are coexisting in a volatile state that has erupted for better and for worse at various moments over the past few years. At times like these, it’s more important than ever to have empathy, to listen to one another, to support each other as best we can. It’s too easy to be drawn into confrontation, which only makes things worse.

“In this context, an exhibit like Keeping the Song Alive, which recounts a significant instance of cross-cultural collaboration, can give us a glimmer of hope and motivate us to work together,” he says. “I hope visitors come away with a deeper understanding of the potlatch and that they’re moved by the beautiful work being done by current indigenous artists featured in the exhibit. While the catalyst for the exhibit was the historic collaboration between Ida Halpern, Chief Billy Assu, and Mungo Martin, that’s merely a starting point for a thread that runs back beyond memory and continues right up to today and into the future.”