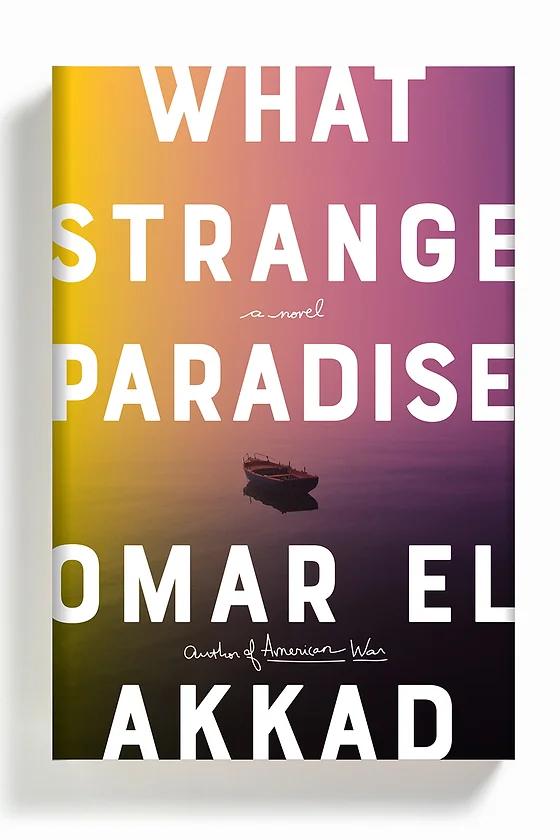

Novelist and journalist Omar El Akkad ponders home truths at the Vancouver Writers Fest

The Giller Prize–winning author of What Strange Paradise has curated a program of events that look at the real world through a literary lens

Omar El Akkad

Vancouver Writers Fest takes place at various venues on Granville Island from October 17 to 23. Omar El Akkad also appears on the Read for The Cure panel with Douglas Coupland and Jann Arden on October 24.

WHEN THE ORGANIZERS of the Vancouver Writers Fest recruited Omar El Akkad to be a guest curator for this year’s edition of the long-running celebration of books and their creators, they didn’t have to ask him twice.

As he explains in a telephone interview with Stir, the Egyptian-Canadian novelist and journalist—who is currently based in Portland, Oregon—might have even been a little too enthusiastic.

“I was thrilled to do it, and I ended up going a bit kid-in-a-candy-store with it,” he admits. “I gave them way more authors and panel ideas than they needed. They sort of had to tell me to stop after a while.”

Among the panel ideas that made the cut are “The Truth Ain’t What It Used to Be: Journalism in the 21st Century” and “Wildness: Stories for an Unraveling World”. The thread that ties the disparate topics together can be summed up in the title of the panel discussion called “What Home Means” (which El Akkad moderates October 18).

“I’d read a lot of really great books over the course of this year,” El Akkad says. “Structurally, narratively, they’re all very, very different, but thematically one of the things that kept coming up was this idea about the uncertainty of home, either by virtue of personal experience or just because of people moving around a lot, or climate change and what it’s doing to people’s perceptions of home. That idea kept coming up over and over again, and so a lot of the panel ideas that I gave them are related to this notion of what home means in a rapidly changing world.”

It’s a topic with personal resonance for El Akkad, who has called a lot of different places home. Born in Egypt and raised in Qatar, El Akkad went to university in Canada before becoming a journalist filing reports from Afghanistan and Guantanamo Bay. His most recent novel, the Giller Prize–winning What Strange Paradise, is about a very different type of journey; it tells the story of a young Syrian refugee who ends up washing ashore on an island after the ship that was carrying him sinks.

It’s not a true story, but it is clearly based in the harsh realities of our current world. Although he initially made a name for himself as a journalist, El Akkad says fiction was his first love, and it’s where he finds the truest sense of home.

“I’ve moved around a lot,” he says. “I’ve been an immigrant from the age of five. I’ve been living on someone else’s land since the age of five, so I don’t have a very good answer to the question ‘Where are you from?’ So in fiction, I find it’s much more easy to manipulate the contours of my made-up world to fit my very specific experience.

“The other reason fiction appeals to me is because it’s where I go to sit with questions for which I don’t have any answers,” El Akkad continues. “Journalism by necessity demands answers. If you don’t have answers to ‘who, what, when, where, how’, you don’t have a piece of journalism. All that said, I find them to be antagonistic muscles, and so I find that some of the best training I’ve ever done for writing fiction came from being in a newsroom for 10 years, and some of the things that differentiated me as a journalist were related to my creative-writing experience.”

Using fiction as a platform to touch on sometimes uncomfortable truths can be a fine balancing act. Moreover, El Akkad is acutely aware that we live in an age in which the lines between fact and intentional disinformation are increasingly blurred. This is the era of Pizzagate and QAnon, when even the most extreme ideas are spread widely on social media and given an air of legitimacy through repetition.

“It used to be that if you wanted to advocate that vaccines are implanting microchips in your body and that there’s a secret pizza-parlour pedophilia ring in DC that all the Democratic elite are engaged in—if you wanted to live in that kind of world, you were by necessity much, much more isolated than you are today,” El Akkad says. “Maybe you find a few likeminded people and maybe you guys exchange a newsletter, but for the most part there was a kind of inherent isolation.

“Today if you believe any of those things, you can find a million Facebook groups. If you want a yoga teacher who believes the same thing, you can find a yoga teacher who believes the same misinformation. The support network has grown to such a point that you can engage in the entirety of a life without ever having to face the inconvenient reality that you believe something deranged. That terrifies me.”

Compounding the problem is the erosion of local news, especially in the United States. According to a 2020 report from North Carolina’s Hussman School of Journalism and Media, in the 15 years leading up to 2020, more than a quarter of the newspapers in the U.S. folded, with half of all local journalists losing their jobs.

Since the beginning of the COVID-19 pandemic, things have only gotten worse. Northwestern University’s Medill School of Journalism, Media, Integrated Marketing Communication recently reported that “the country lost more than 360 newspapers between the waning pre-pandemic months of late 2019 and the end of May 2022.” This left more than a fifth of U.S. citizens living in so-called “news deserts”.

This is a dire predicament for democracy, as Washington Post writer Margaret Sullivan explained in a recent column: “As local news disappears, bad things happen: voter participation declines. Corruption, in business and government, finds more fertile ground. And”—as more people turn to social media to fill the gaps created by the absence of local news—“false information spreads wildly.”

El Akkad is the first to acknowledge that a panel discussion at a literary festival is unlikely to generate solutions to this complex knot of problems. The mere act of talking about these issues—and encouraging others to do the same—is an important first step. Real change, the author asserts, must come at the institutional level.

“We need to start treating humanity as being a vital component of citizenry,” El Akkad says. “There has been a movement over the years to focus on STEM. Wonderful, but I think part of that movement is intertwined with the idea of creating more and more workers, and creating people who can be immediately put to the purpose of generating more value for a corporation. And I don’t know if we are best served as a society by having a lot of people who are incredible at writing code and aren’t entirely sure why fascism is a bad thing. I feel like that’s a really dangerous kind of society to live in.”

As so many things do, it all comes back to the stories we tell. “I think a focus on why we read literature, why it is we engage with each other’s stories, why it’s important to understand history, and to question history—all of these things, I think, maybe are not the solution, but they’re certainly a prerequisite for whatever the solution is.”