Tsering Yangzom Lama examines the humanity of Tibetans at the 2022 Vancouver Writers Fest

The author of We Measure the Earth With Our Bodies says ongoing colonization affects every aspect of Tibetans’ lives

Tsering Yangzom Lama.

Vancouver Writers Fest runs from October 17 to 23 at various venues

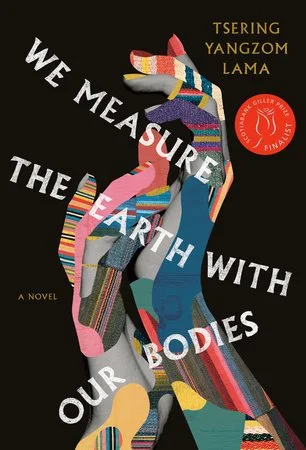

A TALE OF love and separation in the aftermath of China’s invasion of Tibet, We Measure the Earth With Our Bodies (Penguin RandomHouse Canada) tenderly weaves together stories of an exiled Tibetan family through space and time. Tibetan-Canadian author Tsering Yangzom Lama’s first novel is a 50-year journey through the most intimate corners of the hearts of a family, from their escape through the Himalayan mountains in the 1960s to the streets of Toronto’s Parkdale neighbourhood in the 2010s.

The book has been shortlisted for the 2022 Scotiabank Giller Prize and is also on the longlist for the 2022 Centre for Fiction First Novel Prize and Toronto Book Awards. On the heels of those honours, Lama will appear at the 2022 Vancouver Writers Fest for two events: Between The Pages: An Evening with the Scotiabank Giller Prize Finalists on October 17 at 7:30 pm at the Playhouse Theatre (alongside Kim Fu, Rawi Hage, and Suzette Mayr, with moderator Leslie Hurtig) ; and Generational Fiction: Stories of Lineage, History and Things Passed Down on October 21 at 10 am at the Waterfront Theatre (with Aamina Ahmad and Jasmine Sealy, moderated by Marsha Lederman).

“It's my first time attending the Vancouver Writers Festival and I can't believe I'm actually going to be a part of it, I'm really thrilled,” Lama says in a phone interview with Stir. “To meet so many of these amazing writers that are gathering in Vancouver is a huge privilege and a dream come true for me.”

Born in Nepal to an exiled refugee family, Lama immigrated to Vancouver with her family when she was 12. While has had a lifelong love of literature, she says she never considered the possibility of becoming a writer until she was in university.

“By the time I was born, my family had left the refugee settlement, and I was growing up in Kathmandu, the capital of Nepal,” Lama says. “Lots of exiles were living there. Our house was full of lots of relatives, people coming and going, staying for many months at a time. It was an open-door kind of household.

“I have a diary from when I was eight years old, when I was still learning English,” she adds. “My sentences were very basic and some of them are not grammatically correct, but I had written in that diary that when I grew up, I wanted to be a writer.”

When Lama began writing We Measure the Earth With Our Bodies, she was pursuing her master’s in fine arts at Columbia University, which included courses from the Modern Tibetan Studies program and in art history. The classes proved to be invaluable in terms of how her research is informed.

“That really shaped what's become a practice for me, which is to look at artwork as an inspiration for what I write, in the world that I enter,” Lama says. “I spent a year in the library just reading about art and metaphysics, using as much as I could, not always knowing what I was going to do with it, but I found it deeply interesting and personally nourishing. Eventually, I found ways to take those traditions, rituals, and ideas and turn them into narrative devices.

“I was learning a lot about Tibetan women mystics and saints and also the ancient practice of having oracles in Tibet,” she explains. “It’s not thriving in exile and certainly did not do so well because of the Chinese invasion. They treated a lot of practices indigenous to our culture as superstitious and backward and banned a lot of it, although it did persist.”

For We Measure the Earth With Our Bodies, Lama began writing about a village oracle. She was visiting museums in New York City when she came across a small statue, one which inspired that of the novel. The way Lama puts it, she invented her own story for the sculpture. Through her writing, Lama was able to piece together fragments of her history, feeling the weight of the tales she’d uncovered along the way.

“As Tibetan people, whether you're in exile or living inside of Tibet, we're all very aware of the ongoing colonization of our country and the myriad effects for both those inside of Tibet, who are living under immense oppression, and for those of us outside who are denied our homeland and denied access to our heritage and even family back in Tibet,” Lama says. “It touches every aspect of our lives. It affects our relationships with our families, our history, our language. It affects us on an individual level and on a community level. And for me writing in this space, it's also a response to that.

“We’re basically in a space in which the literature that's been created about us is often inaccurate and sometimes really destructive and harmful and perpetuating racist stereotypes, whether from the Chinese side or from Western fetishization of Tibetan people, which is ultimately a form of dehumanization,” she adds. “My writing practice is, I hope, the contrary to that. I’m interested in presenting and examining the humanity of Tibetans, just like any other people.”

The pain that colonization has wrought on the Tibetan people lingers over Lama’s characters, resting alongside their desires and moments of joy, staining their memories. Her story is one of resilience and deals with grief gingerly, creating meaning around the small yet profound moments of beauty.

When asked how she approached narratives of intergenerational trauma in her book, Lama responds: “Well, first of all I don't think about it that way; I don't personally sit down and think about it as like trauma. For me, the entryway is more of the individual characters. I'm thinking about them as individuals, not as representatives of any specific idea or national narrative or framework like trauma.

“A lot of this for me is about spirituality and the ways in which my characters find meaning in their suffering,” Lama says. “And that to me is not about trauma, but about meaning. Growing up, our framework was more about the struggle that we are in as a Tibetan people. We're all engaged in a struggle for our freedom, for our liberation, for our rights, to regain what was stolen from us. And so that's a very different kind of framework than trauma. It's a revolutionary framework. It's a framework of resistance.”

We Measure the Earth With Our Bodies is ultimately a reclamation of the sanctity of Lama’s ancestral traditions, of story, of family, of belonging. In her writing, Lama masterfully weaves beauty with longing, love with sorrow.

“To tell a story is an act of human agency,” Lama says. “And to share a story, to pass a story down, that's somebody’s decision.”

In Lama’s view, there are two ways to think about silence.

“One is the silence that's been imposed on us by our colonizer and also by many world powers that have chosen to stay silent or silence our stories,” Lama says. “So many spaces of power have ignored our existence and our plight. And then there is the silence that is chosen or not chosen by the individual. That's very different. That's not imposed on us, but it's a choice. And so sometimes my characters are silent because they don't want to pass on these stories of suffering to the next generation because they see no purpose in that, or they see that's too painful to do.

“And sometimes, they choose to tell the stories and, and then that story must be understood against all of that silence, whether it's structural and global silence or it's personal silence, born out of love or born out of pain,” she says. “And so then if somebody chooses to tell a story, to share a story, it is deeply sacred in that space because it's either an act of resistance or it's an act of love.”

Lama hopes that by sharing her story, she will be able to carve out a space for young Tibetans in the literary world and help others get to know the real Tibet.

“One thing I hope for on a basic level is that people can see that there is interest, in Canada and elsewhere, for these stories, that these stories matter to people,” Lama says. I know there are many young Tibetans who want to be writers, and I hope that they see that it's actually doable and possible.

“For the broader readership,” she adds. “I just hope that people who read this first of all find a good story, and second of all that it helps them go beyond the sort of very surface level understanding of who Tibetans are, what our experiences are like. I hope that this gives them a little bit more than that. But certainly the headline level understanding of Tibet is something that I think literature gives us the ability to go beyond.”