Vancouver Greek Film Festival review: 01 offers insider's view of a brilliant century in arts

At The Cinematheque, Nanos Valaoritis’s memories of a long life in poetry are like a museum you never want to leave

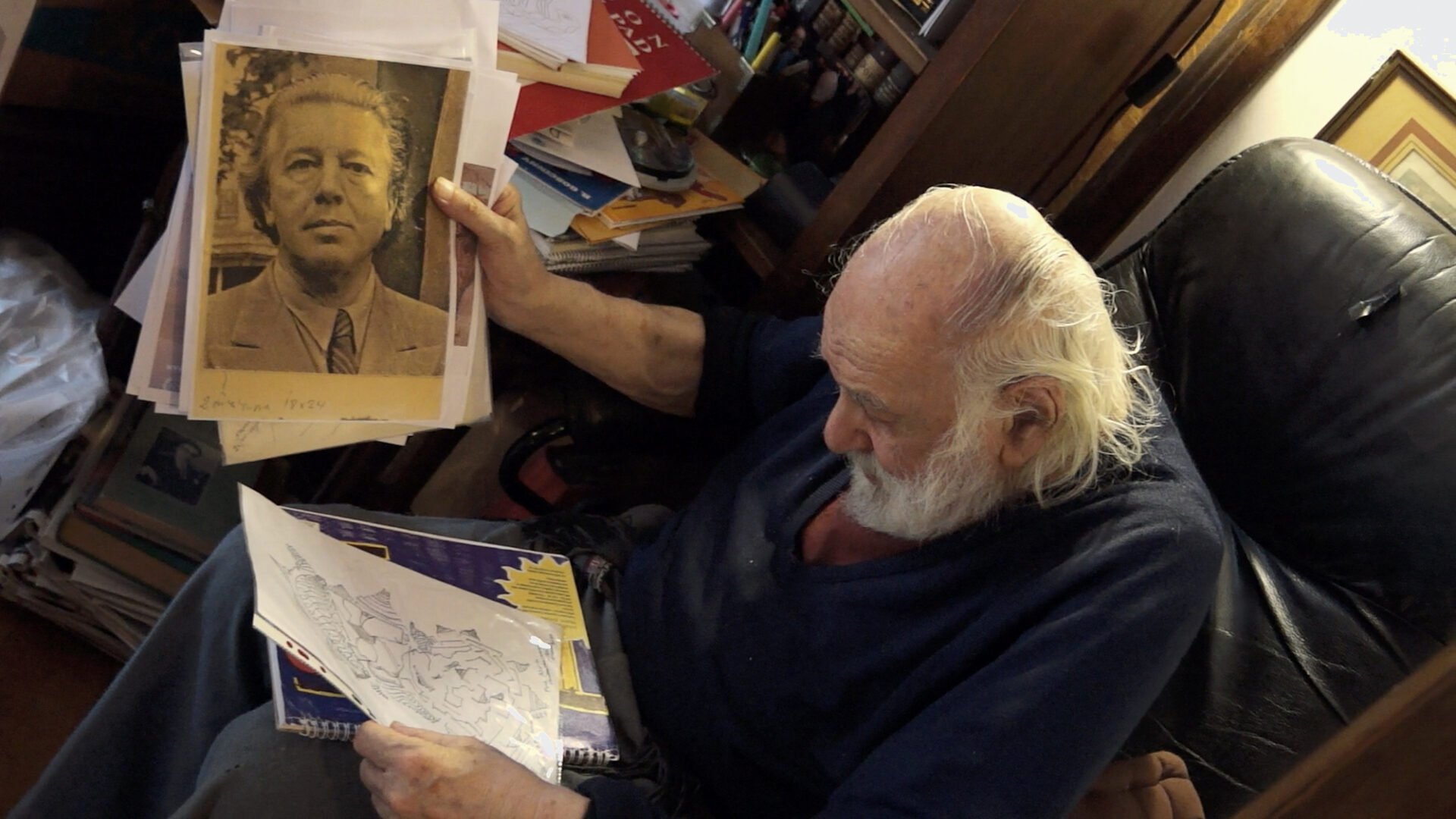

Nanos Valaoritis in Dimitris Mouzakitis’s 01.

The Cinematheque presents 01 as part of the Vancouver Greek Film Festival on March 26 and 31. The festival runs March 13 to April 2

THERE’S SOMETHING SO gloriously claustrophobic about 01, in which we spend 100 minutes in the company of Greek poet Nanos Valaoritis.

Released in 2024, it’s the most recent of the seven features screening at The Cinematheque’s fourth annual Vancouver Greek Film Festival—other titles include 1957’s perennial Boy on a Dolphin starring Sophia Loren, Elia Kazan’s On the Waterfront, and the Theo Angelopolous masterpiece The Travelling Players—but 01 gives us a sprawling, insider’s view of 20th-century arts and letters, almost entirely from inside a cramped and dusty Athens apartment.

Valaoritis spent his life moving between London, Paris, and San Francisco, strolling into historic scenes as he avoided Nazi occupation and Greece’s own military junta. He collected friends like Andre Breton, Picasso, William Burroughs, the Beats, the Yippies, producing his own poetry and publishing underground journals and literary reviews that the 98-year-old, seen here in the last year of his life, frequently describes as “punk”.

As such, we hear personal recollections and ever-so-slightly gossipy remarks on the likes of Francis Bacon and Lucien Freud, who was “a bit of a sadist”. We hear Gregory Corso described as “the worst, a brat, envious and competitive…but a good poet”. He most admires Burroughs and the French artist Francis Picabia, who marginalized themselves but also prevailed out of stubborn independence.

We also see Valaoritis attending an exhibition of his own art in an Athens gallery, a stooped but elfin old man possibly unrecognized by the patrons around him. Later, he’ll recall that Marcel Duchamp scoffed at his work, braying that it was “faux naïf”. His early nude line drawings are in fact very charming, but Valaoritis takes it on the chin, shrugging that he’s just a writer who also paints.

More broadly, he’s a man at the end of a lifelong creative bender, seemingly pulled by mystical force into extraordinary and successive artistic communities. In a film that never loses its hold on the viewer—Valaoritis’s memory is like a museum you never want to leave, same goes for the apartment—it’s the film’s attention to his wife and soul-partner, the great American surrealist Marie Wilson, that perhaps stands out the most, partly because her work is so breathtaking, maybe even supernaturally driven. (He thinks so.)

But it’s also because this little-known and constitutionally modest genius (“her ego was non-existent”) was every bit the equal of their star-studded friends. The great Greek poet Valaoritis is still madly in awe of this woman. ![]()

Adrian Mack writes about popular culture from his impregnable compound on Salt Spring Island.

Related Articles

A panel discussion with workers and community advocates takes place after the VIFF Centre screening

Mareya Shot Keetha Goal: Make the Shot won a spot as best B.C. feature, plus much more as Surrey-based event hands out cash and development support

Moving from architectural marvel to frozen cabin, the film mixes bitter humour with a poetic fugue fuelled by familial trauma

Vancouver director Ben Immanuel drew from his acting students’ real experiences to craft a funny and poignant collaborative film that was years in the making

Program includes Vancouver premieres, returning classics, and a tribute to Tracey Friesen and free screenings on National Canadian Film Day

New paraDOXA initiative will highlight experimental films like To Use a Mountain

Director Mahesh Pailoor and producer Asit Vyas tell the impactful true story of a young man diagnosed with terminal cancer

In Aisha’s Story, a Palestinian matriarch uses food for generational healing, while Saints and Warriors follows a Haida basketball team

Event presented by SFU School for the Contemporary Arts features a screening of In the Garden of Forking Paths

First-time film actor Keira Jang takes a leading role in Vancouver director Ann Marie Fleming’s dark “satire” about a bucolic post-collapse future that comes with a catch

Stunning cinematography and a compelling story make documentary about freediver Jessea Lu a breathless watch

At The Cinematheque, Nanos Valaoritis’s memories of a long life in poetry are like a museum you never want to leave

Program includes Boy on a Dolphin, The Travelling Players, On the Waterfront, and more

Sepideh Yadegar’s film tells the story of an Iranian international student photographed at a Women, Life, Freedom protest in Vancouver

The series presents 14 titles by the master of nonfiction film, rarely seen in the cinema

Housewife of the Year unpacks a long-running Irish TV show, while There’s Still Tomorrow follows a working-class Italian woman in the 1940s

Director Sepideh Yadegar’s debut feature follows Iranian international student Sahar as she stands up for women’s rights in Vancouver

At Vancity Theatre, Christopher Auchter’s film takes us back to the 1985 protest that led to a historic win

La Femme Cachée faces buried trauma; En Fanfare celebrates the power of music; and Saint-Exupéry tells an old-style adventure story

Sweeping biopic returns with nostalgic songs and atmospheric cinematography

Second-annual event opens with Mahesh Pailoor’s Paper Flowers and closes with Enrique Vázquez’s Firma Aquí (Sign Here)